“An Incredible Degree of Rugged and Realistic Training”

The 4th Infantry Division’s Preparation for D-Day

Stephen A. Bourque, PhD

Download the PDF

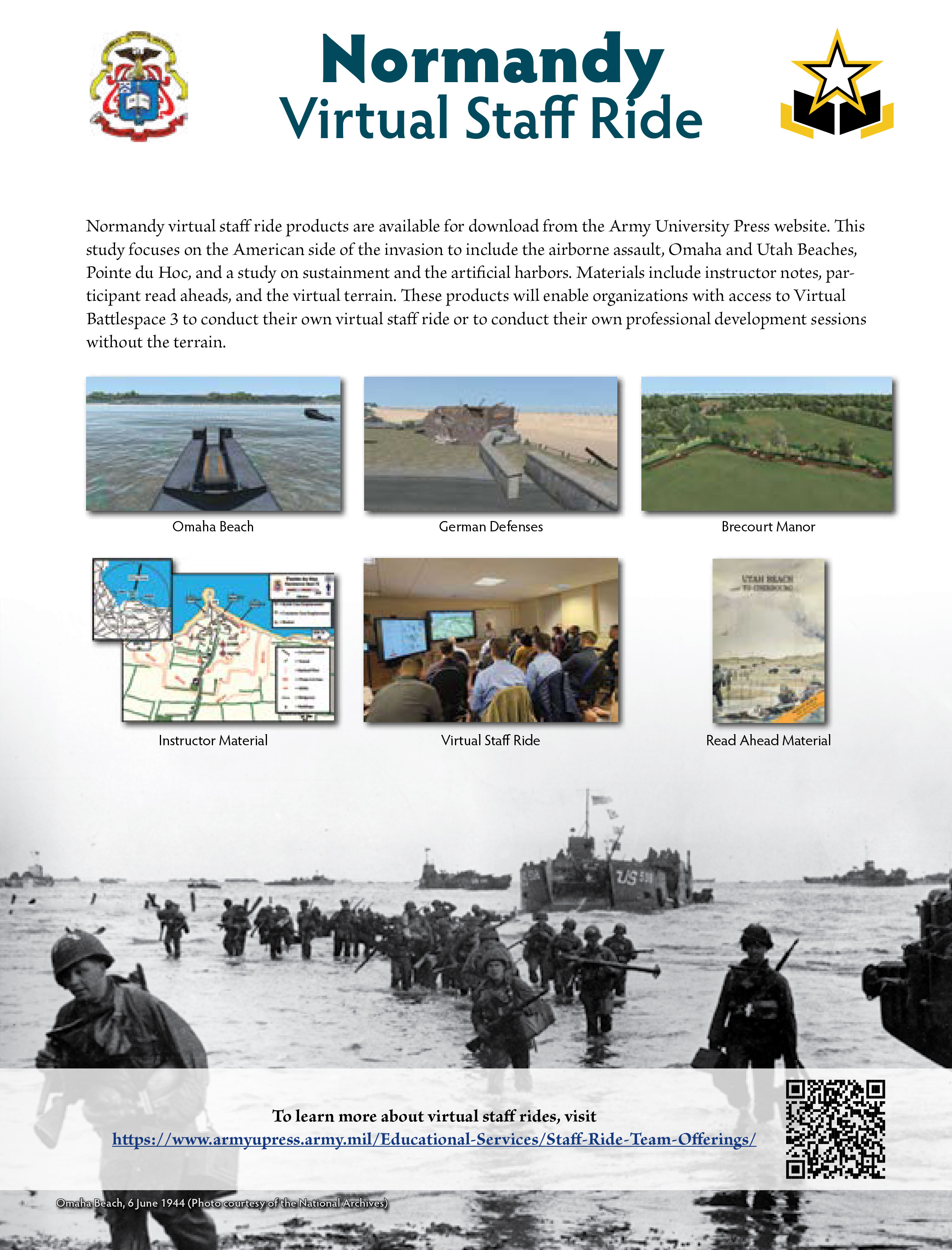

At 0640 hours, 6 June 1944, twenty LCVPs (Landing Craft, Vehicle, Personnel), generally called Higgins boats, stopped just short of the French coast at La Madeleine, near Sainte-Marie-du-Mont on the Cotentin Peninsula. On signal, the ramps lowered, and six hundred soldiers from the 1st and 2nd Battalions of Col. James Van Fleet’s 8th Infantry Regiment jumped into chest-deep water and waded for one hundred yards past obstacles toward the smooth beach. The soldiers’ movement in the icy water was slow as they approached the defenders from the 3rd Company, 919th (German) Infantry Regiment, who were attempting to recover from the Ninth Air Force’s intense and accurate attack on their positions and the massive naval bombardment that had shifted fires only a few moments earlier. The attackers swept through the still-shocked defenders and began moving inland. Ten minutes later, the second wave landed and started expanding the bridgehead. Adjusting to landing about 1,200 yards south of the intended beach, the regiment continued forward toward the causeways and linked up with the 101st Airborne elements that had landed the previous night.

Col. Herve Tribolet’s 22nd Infantry Regiment arrived on the shore at 0745 hours and, as rehearsed, turned north. It headed up the coast to destroy German defenders on the beach and artillery batteries still bombarding the landing area and the fleet. By noon, Col. Russell (Red) Reeder’s 12th Infantry Regiment was ashore, pushing cross-country through the gap between the other two regiments. Throughout the day, tank, tank destroyer, artillery, air defense artillery, and engineer battalions moved in support of their respective regiments or began working on the innumerable tasks assigned by the 4th Infantry Division G-3. By the end of the day, Van Fleet’s regiment had accomplished its primary task of joining with the 101st Airborne Division. The other two regiments had expanded the division’s bridgehead, allowing other elements from the VII Corps to begin coming ashore. Through it all, the 4th Infantry Division commander, Maj. Gen. Raymond O. Barton, who had landed at 0934 hours, watched his soldiers in action. Besides occasionally directing traffic to clear the few roads in the marsh-infested area, he had almost nothing to do. When asked by subordinates for instructions, he told them to execute the plan as practiced.1

Belying Helmuth von Moltke’s often quoted dictum that “no plan of operations extends beyond first encounter with the enemy’s main strength,” almost everything went according to schedule.2 Although problems in water navigation delayed the assault by about ten minutes and shifted the landing by 1,200 yards, almost no one but the first troops ashore even noticed. The German defenders on the beach offered only moderate resistance, and it was primarily their artillery batteries, positioned farther inland, that inflicted most of the division’s 311 casualties—killed, wounded, and missing.3 By the early evening, when Barton arrived at his command post at Audouville-la-Hubert to begin adjusting the plan for the following days, his command was in good shape and either on or close to all its initial objectives. His soldiers had accomplished thousands of individual tasks that day as well as driving the German 919th Grenadier Infantry Regiment away from the beach area. How did this happen?

Most Americans consider D-Day as a singular event: the physical landing of Allied forces, by air and sea, on the Normandy coast. But as soldiers know, many months, if not years, went by before a single Higgins boat touched down on Omaha or Utah beaches. For Americans, the preparation began in 1940 as the United States expanded its military forces. By 1941, the U.S. Army’s Ground Forces, led by Lt. Gen. Leslie McNair, directed a series of large-scale maneuvers in Louisiana and the Carolinas, evaluating and training corps and armies. Specialized unit training for combat in mountains, deserts, and amphibious operations often followed these general maneuvers. One unit that participated in this extensive preinvasion training program was the 4th Infantry Division, one of the three infantry divisions to participate in the Normandy invasion on 6 June. Activated on 1 June 1940, the War Department directed its organization as a motorized division, and three years later, reorganized it as a standard infantry division. Starting in October 1943, it had a specific task: be the lead division in an assault against the German Atlantic Wall. Based on a focused training program developed that month, training began with general amphibious practice in the United States, a second phase with more sophisticated ship-to-shore exercises, and a third phase that rehearsed the invasion. The result was an efficient and productive assault on 6 June.4

Phase 1: Training on Fundamentals in the United States

The onset of war in Europe in 1939 interjected a sense of realism into the U.S. Army’s organization and training. For most, it was not a surprise as many veterans of the First World War sensed that they would again return overseas to finish the job from the previous war.5 Gen. George C. Marshall and other senior leaders began plotting a course to create a ground force capable of doing battle on the continent. The German offensive against France and the Low Countries that accelerated that effort included a significant expansion of the Regular Army and improved training for the National Guard. Between the German invasion of Poland (September 1939) and the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor (December 1941), the War Department created two armored divisions and reactivated six infantry divisions.6 Among these was the 4th Infantry Division, reactivated at Fort Benning, Georgia, on 1 June 1940.7

Almost immediately, replacements began flowing into Fort Benning and its three regiments: the 8th, 22nd, and 29th Infantry (later replaced by the 12th). Congress enacted the Selective Service Act in September 1940, increasing the influx of recruits heading to their new units.8 Until June 1941, the Army had yet to expand its system of replacement centers, so the first time these inductees came face to face with the U.S. Army was when their noncommissioned officers met them getting off their bus. Over the next few months, sergeants instructed them in what has traditionally been called the school of the soldier.9 In addition to the standard tasks of wearing the uniform, marching, military discipline, and marksmanship, the 4th Division’s recruits also had to participate in a unique aspect of training: driving and motor vehicle maintenance. As a motorized division, it had many trucks, tracked vehicles, and jeeps. Many of the recruits, who had grown up during the Great Depression, had no experience with driving vehicles nor how to keep them moving. But it was not long before the division was rolling across the southeast.10

In August 1941, the 4th Motorized Division joined the remainder of the IV Corps during the Third Army Maneuvers in Louisiana. These lasted for ten days and were in preparation for the major exercises scheduled by the General Headquarters, U.S. Army (GHQ). At the end of the exercise, the division returned to Fort Benning for only a short period because, in November, the 4th Motorized participated with the rest of Maj. Gen. Oscar W. Griswold’s IV Corps in the GHQ-directed Carolina Maneuvers. For ten days, it maneuvered as part of the largest concentration of motorized troops in America’s history.11 Returning to Fort Benning on 3 December, it had not yet unpacked when the Japanese navy attacked the Pacific Fleet.12 The troopers remained alert for the next month, waiting to be dispatched to defeat an Axis incursion along the coast. Of course, it did not happen, and the command moved from Fort Benning to its new quarters at Camp Gordon, Georgia, later that month.13 In July 1942, its former chief of staff, Maj. Gen. Raymond O. Barton, returned to command the 4th Motorized Division. Immediately, the division was back in the field.

While Barton’s soldiers were out training, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower’s forces were in their last phase of destroying the German and Italian armies in Tunisia. At the Casablanca Conference in January 1943, the political and military leaders agreed that the Allied subsequent tasks were to clear Sicily, invade Italy, and knock the junior Axis power out of the war. As a result, the War Department sought to get its best-trained unit still in the United States into the next phase of combat. As the “Rolling Fourth” returned to Camp Gordon, Barton received orders to move the division to Fort Dix, New Jersey. By the second week of April, the division was on the move, this time by train-hauling all its equipment.14 When they arrived, the troops continued to train with more weapons firing, small-unit attacks on fortified positions, and air-ground operations. Mortar crews received special training attention since they gave the infantry battalion commander his best fire support for close-in combat.15

This well-trained unit was not deploying to Italy due to its organization as a motorized division. In theory, there would be one of these for every two armored divisions, essentially replicating how the Germans had developed their panzer grenadiers to support their panzer divisions. However, because of the large amount of shipping required to get it overseas, as much as a standard armored division, it did not deploy. By the end of July 1943, the War Department decided to discard the motorized structure and redesignate these units as infantry divisions. On 24 August, GHQ ordered Barton to turn in his motorized equipment and prepare to move to the Amphibious Training Center, Camp Gordon Johnston, on the Florida Coast.16

Privately, a member of the GHQ staff let Barton know the 4th Division would be part of the assault on France, code name Overlord. In September, he flew to England for a general briefing on his role and to examine potential training and bivouac areas. When he arrived at Gordon Johnston in early October, he and his staff prepared a training memorandum (Number 73), published on 14 October, which spelled out the division’s training plan for the next nine months. It identified three training phases: the first was an introduction to amphibious operations and honing small-unit skills in Florida between 18 October and 31 December. Phase 2 would commence after the division arrived in the United Kingdom in January and, although not stated in the memorandum for security reasons, would focus on more sophisticated ship-to-shore operations. Once the assault plan was firm, Barton’s command would concentrate on practicing for the invasion.17

The War Department had established the Amphibious Training Center in October 1942 near the beach town of Carrabelle, Florida, about sixty miles southwest of Tallahassee. The training area was large enough to accommodate an entire reinforced infantry division. While the instructional program was always in flux, depending on the unit, it generally consisted of several different phases:

- Embarkation operations

- Activities while afloat and en route to the landing location

- Movement from the ship to the shore

- Initial assault operations18

In addition, staff officers participated in a separate course emphasizing the role of the headquarters in planning for all phases of the assault. Finally, the center taught a series of special subjects, including swimming, physical conditioning, knife and bayonet fighting, and automatic weapons firing from landing craft. By the time the 4th Infantry Division arrived in September 1943, the center had been in operation for more than a year and was changing from a purely Army endeavor to a joint Army-Navy operation.19

For Phase 1, amphibious operations were the most crucial task, followed by other essential skills such as mine laying, sanitation, patrolling, and night operations. During assault training, the division used live ammunition when possible and emphasized the use of the bayonet. In addition to regular exercises, officers and noncommissioned officers attended schools on leadership and tactical subjects. Physical fitness was essential, and the division conducted long-distance cross-country runs at least once a week. They would practice marching, with full gear, from distances of fifteen to twenty-five miles.20

The details for much of the training was a 271-page syllabus titled “Shore to Shore Amphibious Training.” It covered nearly everything a unit could expect to experience, from loading the vessels to landing on the far shore, communicating during the passage to the coast, and the beach organization after landing. It also had a series of tutorials for commanders and staff on how to write an amphibious order. This program ended with a series of exercises designed to put everything the soldiers and their leaders learned into practice.21

The training program was challenging and demanding. Soldiers working with the 4th Engineer Special Brigade got seasick for the first time as they spent hours offshore, bobbing in their landing craft. They landed at night on beaches on local islands and the Florida coast. They hiked at night to build physical fitness while avoiding the day’s heat. They went swimming every afternoon to learn how to escape a sinking ship and reach the shore. Combat teams practiced, for the first time, as units comprising infantry, engineers, medics, and artillery. While not on the prescribed training plan, the division ran a modified “Ranger” training plan for select members of each regiment. Capt. Oscar Joyner Jr., a former Amphibious Training Center staff member who was now with division G-3, ran this program. Its essence was on essential individual skills such as map reading, land navigation, use of explosives, detecting mines and booby traps, and scaling defensive walls. As the historian for the 22nd Infantry noted, “Probably no phase of the training of the regiment was more useful or more thoroughly detested than the time spent at Camp Gordon Johnston, Florida.”22 By the end of November, these young men were in the best physical condition of their lives, lean from the exercise and tan from hours in the sun. They were ready for the next training phase in England.23

Phase 2: General Amphibious Training in the UK

The 4th Infantry Division began its journey to Europe by leaving Camp Gordon Johnston on 1 December. Wheeled vehicles moved by convoy the 450 miles from the coast to Camp Jackson, South Carolina. There, it cleaned or replaced worn-out clothing and equipment. The division started moving again at the end of December, this time to Camp Kilmer, New Jersey, where they prepared for deployment. War Department inspectors and offices from various agencies moved soldiers through one last series of predeployment checks during the day. Soldiers received physical examinations and lectures on security, and they removed all their unit patches and insignia. The men filled in the change of address cards and sent them home with any items they were not permitted to take with them. The War Department alerted the division for deployment at the end of December, and its advanced party, led by Col. James Rodwell, the chief of staff, departed New York Harbor on 27 December. Finally, Van Fleet’s 8th Infantry was first, leaving on 10 January on the RMS Franconia, a Cunard liner. By 19 January, the entire division was at sea. It took thirteen days to cross the icy Atlantic Ocean. By the end of January, the whole division had arrived at Liverpool, and the debarkation process began.24

The Ivy Division’s movement was part of Operation Bolero, the U.S. Army and Army Air Forces’ deployment to England. The Bolero Combined Committee (London) supervised the “reception, accommodation, and maintenance of US forces in the United Kingdom.”25 This group coordinated with all British national and local government elements to ensure the process was as smooth as possible. It supervised the terrain and facilities for American troops and designated billeting areas. From Liverpool, the division’s soldiers boarded trains and moved to their encampment areas in the large peninsula in southwest England called Devon (or sometimes Devonshire). One reason the committee selected this location is that it made amphibious training in English and Bristol Channels relatively easy. It was also close to the embarkation ports and the ultimate landing areas in western Normandy.26 As soon as he arrived, Barton reported to Lt. Gen. Omar N. Bradley, the commander of the First U.S. Army, to get his briefing on what was to expect over the next few months.27

The headquarters was at a lovely early eighteenth-century mansion in Tiverton called Collipriest House. The division artillery headquarters was in the nearby village of Cullompton, with the battalions scattered near their supported regiments. Col. Harry Henderson’s 12th Infantry Regiment moved into the area around Exeter. Van Fleet’s 8th Infantry centered its command on Honiton, and Tribolet’s 22nd Infantry moved into various villages in and around Newton Abbot. The distance from division headquarters to the various headquarters could be over forty-five miles, making it a challenge for Barton and his staff to interact with his commanders, who now were pretty much on their own when not on training exercises.28

As soon as the regiments were in place, they began small-unit training to prepare for the more extensive exercises. Training space in the British countryside was at a premium. Soon, the American theater command arranged for the division to practice at an area they called the U.S. Army Assault Training Center, located between Braunton and Barnstaple. Here, the division’s troops could practice with infantry weapons, tanks, artillery, and air support, all using the same ammunition they would use in combat. At Braunton, soldiers learned or refreshed their memories on organizing boat teams, leading assault groups, and overcoming “hedgehogs” and other obstacles enemy defenders could use to stop the division’s assault.29 Since Barton had decided to lead the invasion with the 8th Infantry, he sent it immediately to Braunton. Its specialized training included assault amphibious techniques, reduction of beach defenses, and assault against fortified locations. As the division historian noted, “The training at Braunton was well organized, intensive, interesting, and of immense practical value to its recipients.”30 The remainder of the division spent February practicing with its new equipment at the company and battalion levels. This training included live-fire exercises and shooting direct and indirect fire over the assaulting troops.31

On 23 January, Eisenhower, now the supreme allied commander, notified the Combined Chiefs of Staff that he had approved a significant modification in the invasion concept. Because the Allies’ posture for men and material had improved since the original invasion plan’s development, they could now assault another beach, called Utah, on the Cotentin Peninsula. Bradley assigned this mission to the 4th Infantry as part of the VII Corps. The division had the task of seizing that beach, linking up with two divisions of airborne forces dropped inland, and turning north to lead the effort to capture the port at Cherbourg.32 Since Eisenhower and Bradley’s staffs had not yet worked out the invasion’s details, Barton and the 4th Infantry Division continued execution of Phase 2 of his October training plan.33

Then they jumped into the icy water, often up to their armpits, and waded to shore. It was a harrowing experience with the constant danger of injury or drowning, and everyone was always wet and cold.

Meanwhile, from February until 5 June, the division commander participated in an almost daily sequence of visits, meetings, and inspections. Barton’s diary records each of these, consuming more than half of the time he had available to prepare his command. The U.S. secretary of war, the British prime minister, and almost every general officer and staff colonel in both armies made their way to his headquarters at Tiverton. Barton met with members of the corps headquarters almost daily. With more than thirty years of infantry service, “Tubby” Barton knew and had served with many of the American officers. Therefore, in this environment of constant activity, there was little time for reflection and contemplation by a division commander on the eve of one of America’s most important battles.34

The division needed to hone its general amphibious skills as part of Phase 2 training. The 8th Infantry had begun this process at Brauton in late February. It started for the 12th Infantry with Operation Muskrat, on 12 March. At Plymouth, three assault transport ships awaited them: the USS Dickman, the USS Barnett, and the USS Bayfield, which would be the corps and division command post during the invasion. They headed north to the Firth of Clyde, southwest of Glasgow, Scotland. There, they dropped anchor, and for the first week, the battalions practiced various drills such as reaching boat stations under blackout conditions, debarking over the sides of the ships, and wearing full gear with ladders, nets, and ropes. Throughout the week, soldiers experienced cold rain and the expected seasickness caused by bouncing around in the late winter coastal waters. For the following week’s exercise, a detachment from the 1st Engineer Special Brigade boarded the three ships. Now, the soldiers put their training to use as they organized into boat teams, scurrying down the transports’ sides and into their assigned Higgins boats. They formed up into assault waves and approached the hostile shore. Then they jumped into the icy water, often up to their armpits, and waded to shore. It was a harrowing experience with the constant danger of injury or drowning, and everyone was always wet and cold.35

Barton had watched the final exercise from a high point overlooking the beach until thirty minutes after the troops landed. He then went down to the beach. He was displeased by what he found. The soldiers seemed listless and unmotivated. In most cases, they were going through the motions, not using the terrain for cover and hiding from direct enemy fire. More importantly, leaders were not taking charge and making corrections from his perspective. He found Henderson and took him up and down the beach, pointing out what he saw. The regimental commander had not been with the division very long, and Barton was not impressed with what he discovered.36

The 22nd and 8th Infantry went through similar exercises. Tribolet called his training series Mink, which occurred at Slapton Sands. Unlike the 12th Infantry, he only had to qualify two battalions since the 3rd Battalion would train with Van Fleet’s regiment. He practiced the same drills as the Muskrat exercise. Meanwhile, the 8th Regiment, including the 3rd Battalion of the 22nd Infantry, moved to Dartmouth and continued its assault training in another exercise called Otter during the same period. Since Van Fleet would be first on the shore, he demanded that its practice be more in-depth with an increased sense of urgency.37

Phase 3: Preparing for Neptune

By mid-March, the First Army and VII Corps commanders and staffs had made most of the central planning decisions. Although the VII Corps would not publish Field Order #1, Neptune, until 28 May, Barton knew that Maj. Gen. J. Lawton Collins, the corps commander, had assigned the 4th Infantry Division the task of landing on the Cotentin Peninsula, linking up with the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions, and driving north toward Cherbourg. It was time for him to move to Phase 3 of his training plan, preparing for the invasion.38

The first significant invasion rehearsal was Exercise Beaver; running from 27 to 30 March, this would be a full rehearsal of the anticipated assault, with the 8th and 22nd Infantry leading the way. Now, the regiments were combined arms organizations called regimental combat teams. In addition to the infantry, the division assigned them tank platoons, engineers, medics, signal troops, and a direct support artillery battalion. In many cases, these attachments would continue for the war’s duration. For this exercise and the invasion, the 1st Engineer Special Brigade and the 1106th Engineer Group joined the 4th Division. Since this was a VII Corps-directed activity, Collins and his headquarters also controlled the 101st Airborne Division’s 502nd Parachute Infantry Regiment and received support from the Ninth Air Force.39

The exercise would take place at the Assault Training Center at Slapton Sands on the south Devon coast, west of Dartmouth. It was a seven-mile-long beach, and possessed terrain similar to that which the Americans would encounter in June. Of special note was the Slapton Ley, a salt marsh just behind the beach that mirrored almost exactly the situation at Utah Beach.40

Using the draft 4th Infantry Division field order as a guide, the 8th Regimental Combat Team led the way, followed by the 22nd and 12th Regimental Combat Teams. It was the first significant rehearsal of the division’s assault plan. Disembarkation and the beach assault went generally according to schedule. The assault units secured a bridgehead and moved inland. But Barton was not happy with the performance of some of his companies and battalions.41

The following day, the exercise continued. It was time for the logistics units to begin supporting the combat teams on the shore. The European Theater Service of Supply landed about 1,800 tons of food, fuel, and ammunition, allowing everyone to practice resupply operations. That evening, the combat units began returning to their Devon camps. At the same time, the division commander and his operations group went to Plymouth and met the naval task force commander, Adm. Don P. Moon, Collins, and the VII Corps staff. As a training exercise of this scale, it exposed many flaws in unit training and Army-Navy cooperation. Many participants remembered it as a too confusing event. Based on his performance over the last month, Barton replaced one of his regimental commanders, Col. Harry Henderson, from the 12th Infantry. Bradley sent him Col. Russell P. “Red” Reeder Jr., one of Marshall’s young protégées who had just arrived in the theater to replace him.42

Early discussions about Exercise Tiger began almost as soon as Eisenhower and British Gen. Bernard L. Montgomery, the ground force commander, arrived in England in February, and they agreed to add another invasion beach. Bradley, therefore, ordered Collins to start planning for the exercise on 1 April, with the execution date during the last week of the month. As this was a dress rehearsal, the task organization was the same as the corps would employ on Utah Beach in June. The 4th Infantry Division would land as scheduled by sea, supported by the 1st Engineer Special Brigade to clear the beaches of mines and obstacles. It was not practical to use large amounts of aircraft to ferry the airborne troops from the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions; these troops arrived by truck to simulate the link-up with the forces landing by sea on D (execution day) +1. That same day, the logistics train of quartermaster, medical, and other sustaining units would also rehearse its landing and establishment of the supporting element on the invasion beach.43

Using the draft VII Corps Field Order #1, Neptune, as the guide, Barton and his staff prepared Field Order #1, Exercise Tiger, on 18 April.44 The division would employ its three regiments, now configured as combat teams with all supporting engineers and tanks, precisely as planned for the invasion. Van Fleet’s Combat Team 8, reinforced by the 3rd Battalion, 22nd Infantry, led the way and would move to Lower Ley to secure the causeway location. Tribolet’s Combat Team 22, minus the battalion under Van Fleet’s control, would be the next wave. Its mission was to land on the beach, secure a causeway, and take command of its 3rd Battalion. Then, it was to continue the attack along its assigned avenue of advance. Reeder’s Combat Team 12 landed next with the task to secure a river crossing location. The 1st Engineer Special Brigade was mixed among the division, supporting the landing and improving the beach for follow-on forces and supplies. Finally, following the assault troops would be divisional, corps, and army supply units, practicing the movement of needed ammunition and food from ship to shore. This training event was as close to the invasion as the VII Corps staff could plan and execute.45

Over thirty thousand soldiers headed to the embarkation ports on 22 April, arriving at assembly areas off Devon’s south coast a few days later. Thursday, 27 April was a beautiful day for a practice invasion, and the live-fire bombardment was ready to go. However, for various reasons, Moon postponed the assault from 0730 to 0830 hours, never something to try at the last minute. The element of friction, described by Carl von Clausewitz, took charge.46 Not all the ships got the word. Companies E and F, 8th Infantry, received the change of orders and held back. However, Company G, the reserve unit, never got the message and continued ashore as scheduled. They were alone on shore as the Navy began its rescheduled bombardment. Fortunately, the heavy guns hit no one, but some explosions got a little too close to some of the troops on the beach.47

The division had other problems; Barton and senior commanders sensed a lack of energy across the command. Soldiers failed to employ the fundamental aspects of cover and concealment as if it were an invasion. Part of the problem was the absence of the regimental commanders with the initial landings. Van Fleet and Tribolet were stranded on a “free boat.” Theoretically, they had the option to land anywhere, thus placing the regimental commanders where needed. However, the British skipper had other ideas and did not get them onto the beach until much later. When Barton landed, he received a profane-laced narrative from Van Fleet, who had been denied the chance to correct the problems in his team. Not long after, around 1045, Barton encountered Montgomery; Adm. Bertram H. Ramsay, commanding the Allied Naval Force; and Lt. Gen. Courtney Hodges, Bradley’s deputy commander, on the beach. Not knowing the landing problem’s background, Montgomery confronted the division commander. “Where the devil are regimental commanders, now General, they must be with the troops during the landing.” Quite offended, Barton replied, “Now listen to me, General, you better tell that to your British skipper, my commanders would be in here but for his inefficiency.” Montgomery pulled back and discussed the issue with Ramsay.48

Although this was the most critical training event for the 4th Infantry Division, Exercise Tiger has also gone down in history as one of the U.S. and British Navy’s most significant failures in the European Theater of Operations. Early in the evening on 27 April, a convoy of eight LSTs (Landing Ship, Tank) departed Plymouth and headed for an assembly area in Lyme Bay, east of the exercise landing area. These large vessels, each four hundred feet long and capable of carrying twenty tanks and more than two hundred soldiers, were the backbone of the Allied invasion force. Onboard this convoy was the follow-up force for the landing, including soldiers and equipment providing engineer, logistics, medical, and communications support. Many of these were from the 1st Engineer Brigade. Shortly after midnight on 28 April, nine German torpedo boats left Cherbourg harbor to investigate the reported activities near Plymouth. Making contact with the Allied vessels around 0200, they encountered the LSTs and began their attack. When it was over, and British patrol ships arrived to chase them away, the German vessels had sunk two landing craft (LST 507 and LST 531), damaged two more, and killed approximately eight hundred Allied soldiers and sailors. Fearful that news of their success could tip off the Germans to the impending invasion, Allied headquarters slapped a security quarantine around the area. They warned medics and those aware of the disaster to say nothing. Senior officers of both nations and services pointed fingers at each other, assigning blame for the tragedy. Like most military actions, the event’s details remained classified until the war’s end.49 Like many such instances, however, most considered it the price of preparing for the invasion and moved on. Moon had the grace to send a note to Collins to “express my deepest sympathy for their (1st Engineer Special Brigade) losses suffered on our first joint contact with the enemy.”50

Conclusion

The U.S. Army’s assault on the Normandy coast did not just happen. It took many months of training and practice to ensure that all the complex aspects of the invasion would come together to produce tactical success. The 1st and 29th Infantry Divisions had training programs similar to the 4th Infantry Division in preparation for their assault on Omaha Beach. It was the same for the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions that practiced for their night drops before the naval assault. The British and Canadian soldiers, who would land on Gold, Juno, and Sword beaches, also participated in extensive amphibious training programs. As historian Peter Caddick-Adams pointed out in his introduction to Sand & Steel, “When compared with the Germans, most servicemen who assaulted northern France had experienced an incredible degree of rugged and realistic training that put them at the peak of physical fitness, acclimatized them to battle, and equipped them mentally and physically well enough to win.”51 For Raymond O. Barton’s Ivy Division, this rugged and realist training began on the warm shores of the Gulf of Mexico and ended on the frigid shore of Slapton Sands eight months later.

Notes

- George L. Mabry, “The Operations of the 2nd Battalion 8th Infantry (4th Inf. Div.) in the Landing at Utah Beach, 5-7 June 1944 (Normandy Campaign) (Personal Experience of a Battalion S-3)” (student paper, Infantry Officer Advanced Course, Donovan Research Library, Fort Moore, GA, 1947); Raymond O. Barton, “War Diary: March 1944 to January 1945,” Barton Personal Papers, private Barton family collection (Barton Papers); Roland G. Ruppenthal, Utah Beach to Cherbourg (1948; repr., Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History [CMH], 1984), 43–47.

- Daniel J. Hughes, ed., Moltke on the Art of War: Selected Writings (Novato, CA: Presidio, 1993), 45.

- Joseph Balkoski, Utah Beach: The Amphibious Landing and Airborne Operations on D-Day (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2005), 330.

- G-3, 4th Infantry Division, “Training Memorandum 73: Training Directive, 18 October 1943-16 March 1944,” 14 October 1943, entry 37042, box 3320, 4th Infantry Division Memos, Training, Record Group (RG) 338 (Army Organizations), National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD (NACP).

- Raymond O. Barton, “Letter to Clare Conway Barton, May 10, 1940,” Barton Papers; Peter J. Schifferle, America’s School for War: Fort Leavenworth, Officer Education, and Victory in World War II (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2010), 14–15.

- Kent Roberts Greenfield, Robert R. Palmer, and Bell I. Wiley, The Army Ground Forces: The Organization of Ground Combat Troops (1947; repr., Washington, DC: U.S. Army CMH, 1987), 9–10.

- John B. Wilson, Armies, Corps, Divisions and Separate Brigade (Washington, DC: U.S. Army CMH, 1987), 187; Raymond O. Barton, The 4th Motorized Division, Camp Gordon, GA (Augusta, GA: Walton Printing, 1942), 12. Fort Benning was renamed Fort Moore in 2023.

- John B. Wilson, Armies, Corps, Divisions and Separate Brigade (U.S. Army CMH, 1987), 187; Raymond O. Barton, The 4th Motorized Division, Camp Gordon, GA (Augusta, GA: Walton Printing, 1942), 12. The Army renamed this post Fort Moore in 2023.

- 4th Infantry Division Headquarters, “Narrative History, 4th Infantry Division, June 1940-March 1946,” 2, entry 427, box 5663, RG 407 (World War II Operational Reports), NACP; Leonard L. Lerwill, The Personnel Replacement System in the United States Army, Department of the Army Pamphlet No. 20-211 (Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 1954), 247–49. Note: Most VII Corps and 4th Infantry Division records may also be found in the War Department Microfilm Collection at the Combined Arms Research Library, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

- Christopher R. Gabel, The U.S. Army GHQ Maneuvers of 1941 (Washington, DC: U.S. Army CMH, 1991), 27–29.

- Kent Roberts Greenfield and Robert R. Palmer, Origins of the Army Ground Forces General Headquarters, United States Army, 1940-1942, Study No. 1 (Washington, DC: Headquarters, Army Ground Forces, 1946), 24, https://cgsc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p4013coll8/id/4437/rec/1; Gabel, The U.S. Army GHQ Maneuvers, 133–35, 155–57.

- Gerden F. Johnson, History of the Twelfth Infantry Regiment in World War II (Boston: National Fourth [Ivy] Division Association, 1947), 35.

- Ibid., 36. Fort Gordon was renamed Fort Eisenhower in 2023.

- Information Office, U.S. Army Training Center, History of Fort Dix, New Jersey, 1917-1967 (Fort Dix, NJ: U.S. Army Training Center, 1967), chap. 9.

- Johnson, History of the Twelfth Infantry Regiment, 39.

- General Staff War Department, “Memorandum for Commanding General, Army Ground Forces: Amphibious Training, 18 August, 1943,” RG 337 (Records of Headquarters Army Ground Forces), NACP; Greenfield, Palmer, and Wiley, Organization of Ground Combat Troops, 338–39; Wilson, Armies, Corps, Divisions and Separate Brigades, 197.

- “Army Retirement Board Proceedings: Raymond O. Barton, September 29, 1945,” RG 319 (Records of the Army Staff), National Archives at Saint Louis. Barton reveals he went to England in September 1943. Training Memorandum 73, RG 338, NACP.

- Marshall O. Becker, The Amphibious Training Center: Study No. 22 (Washington, DC: Historical Section, Army Ground Forces, 1946), 4, 57–70; Peter T. Wolfe, Training Memorandum Number 2, RG 337, NACP.

- Ibid.

- Training Memorandum 73, RG 338, NACP.

- “Syllabus,” Headquarters, Amphibious Training School, 1 October 1943, RG 337, NACP.

- Johnson, History of the Twelfth Infantry Regiment, 40.

- Bill Boice, History of the Twenty-Second United States Infantry Regiment in World War II (self-pub., 1959), 2; Andrew Haggerty, “Three Generals, Staff Officers, Swim Their Fifty Yards,” The Ivy Leaf: Weekly Newspaper of the 4th Infantry Division, 11 November 1943.

- Boice, History of the Twenty-Second United States Infantry Regiment, 2–3; Paul F. Braim, The Will to Win: The Life of General James A. Van Fleet (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2008), 66–67; Johnson, History of the Twelfth Infantry Regiment, 41–44.

- Findlater Stewart, “Subject: American Forces in the United Kingdom: Reception and Liaison Arrangements Bolero Combined Committee,” letter to John Maude, Minister of Health, MH79/571, The National Archives of the UK.

- Roland G. Ruppenthal, Logistical Support of the Armies, Volume I: May 1941-September 1944 (1953; repr., Washington, DC: U.S. Army CMH, 1995), 54, 61–65.

- Headquarters, 4th Infantry Division, “Narrative History, 4th Infantry Division, June 1940-March 1946,” 7, RG 407, NACP.

- Ibid.; Boice, History of the Twenty-Second United States Infantry Regiment, 4; Johnson, History of the Twelfth Infantry Regiment, 45; H. W. Blakeley, 4th Infantry Division (Yearbook), 1941–48 (Baton Rouge, LA: Army and Navy Publishing, 1946), 78.

- Johnson, History of the Twelfth Infantry Regiment, 46; “Welcome to Braunton,” Braunton Countryside Centre, accessed 15 March 2024, https://www.brauntoncountrysidecentre.org/explore-braunton/.

- Narrative History, RG 407, NACP.

- Ibid.

- Stephen C. Kepher, COSSAC: Lt. Gen. Sir Frederick Morgan and the Genesis of Operation Overlord (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2020), 214; Alfred D. Chandler Jr. and Stephen E. Ambrose, eds., “Cable, Eisenhower to Combined Chiefs of Staff, January 23, 1944,” The Papers of Dwight David Eisenhower: The War Years, vol. III (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1970), 673–74.

- Training Memorandum 73, RG 338, NACP.

- Barton, “War Diary,” Barton Papers.

- Johnson, History of the Twelfth Infantry Regiment, 47–49; Clifford L. Jones, “Part VI, Neptune: Training, Mounting, The Artificial Ports,” in The Administrative and Logistical History of the ETO (Washington, DC: U.S. Army CMH, 1946), 240, https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/ETO/Admin/ETO-AdmLog-6/index.html.

- Barton, “War Diary,” Barton Papers.

- Boice, History of the Twenty-Second United States Infantry Regiment, 4–5; Jones, Administrative and Logistical History, 240.

- VII Corps G-3, “Field Order #1 (Neptune),” 28 May 1944, RG 407, NACP.

- Jones, Administrative and Logistical History, 241.

- Ibid., 240; Peter Caddick-Adams, Sand & Steel: The D-Day Invasion and the Liberation of France (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), 198–99.

- Jones, Administrative and Logistical History, 242; 4th Infantry Division G3, “Field Order #1, May 12, 1944, Neptune,” 1944, entry 427, box 5763, RG 407, NACP; 4th Infantry Division Headquarters, “History of the 4th Infantry Division (SHAFE Background),” 8, RG 407, NACP; Barton, “War Diary,” Barton Papers.

- Barton, “War Diary,” Barton Papers; “COL (R) Russell P. Reeder, Jr. ’26,” West Point Association of Graduates, accessed 6 March 2024, https://www.westpointaog.org/DGARussellReederJr1926; Christopher D. Yung, Gators of Neptune: Naval Amphibious Planning for the Normandy Invasion (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2006), 159–60.

- Jones, Administrative and Logistical History, 253; VII Corps G-3, “Field Order #1(Neptune),” 28 May 1944, RG 407, NACP.

- 4th Infantry Division G3, “Field Order #1, Exercise TIGER,” 18 April 1944, RG 407, NACP; Jones, Administrative and Logistical History, 255–56.

- Ibid.

- Carl von Clausewitz, On War, ed and trans. Michael Howard and Peter Paret, indexed ed. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984), 119–21.

- Jones, Administrative and Logistical History, 254–55; Yung, Gators of Neptune,161; Stephen P. Cano, ed., The Last Witness: The Memoirs of George L. Mabry, Jr. from D-Day to the Battle of the Bulge (Fresno, CA: Linden Publishing, 2021).

- Raymond O. Barton, interview by Cornelius Ryan, box 013, folder 07, Cornelius Ryan Collection of World War II Papers, Ohio University Libraries Digital Archival Collections, https://media.library.ohio.edu/digital/collection/p15808coll15/id/17349/rec/1.

- Jones, “Administrative and Logistical History,” 257–63; Charles B. MacDonald, “Slapton Sands: The Cover-up That Never Was,” Army 38, no. 6 (1988): 64–67; Caddick-Adams, Sand & Steel, 238–39; Yung, Gators of Neptune, 165–67.

- “Letter Moon to Collins,” 29 April 1944, J. Lawton Collins Papers, 1914–1975, Dwight David Eisenhower Presidential Library, Abilene, Kansas.

- Caddick-Adams, Sand & Steel, xxxviii.

Stephen A. Bourque, PhD, is professor emeritus at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College. He left the U.S. Army in 1992 after twenty years of enlisted and commissioned service, with duty stations in the United States, Germany, and the Middle East. After earning a PhD in history at Georgia State University, he taught at several colleges and universities, including California State University-Northridge, and the Command and General Staff College’s School of Advanced Military Studies. His books include Jayhawk! The VII Corps in the 1991 Persian Gulf War (U.S. Army Center of Military History, 2002), The Road to Safwan (University of North Texas Press, 2007), and Beyond the Beach, the Allied War against France (Naval Institute Press, 2018). His most recent book, “Tubby,” Raymond O. Barton and the US Army, 1889-1963, is scheduled for publication in fall 2024. Portions of this article will appear in Tubby. Bourque is currently working on a book on the 4th Infantry Division’s battle in the Hürtgen Forest.

Back to Top