Operational Myopia

A Fatal Fallacy

Col. Daniel Sukman, U.S. Army

Download the PDF

“A concept is an idea, a thought, a general notion.”

—Gen. Donn Starry

The joint force lacks a unified theory of success for the strategic level to war. Recent conceptual work in the joint community is producing a joint warfighting concept and joint concept for competing, which respectively focus on battle and actions before the onset of crisis and conflict. Moreover, each service is developing theories of victory independent of each other and independent of the joint community. Conceptual production from the services includes multidomain operations and distributed maritime operations, both of which center on battles at the operational level of war; while this is necessary, it is not sufficient. Without a unified and overarching strategic approach to war, the joint force is accepting the same risk as Napoleon Bonaparte in the early nineteenth century, the Germans (twice) in the first half of the twentieth century, and to an extent, the same risk the United States took in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The Current State of Strategic Concepts

In 2012, the joint staff produced the Capstone Concept for Joint Operations (CCJO). This concept provided a strategic vision for the military to become a globally integrated joint force. Under the guidance of then–Chairman Gen. Martin Dempsey, the CCJO recognized that the future of war would encapsulate enemies and adversaries who operate across combatant command boundaries and in all five domains (air, land, maritime, space, and cyberspace).1 The joint staff continued with the publication of the 2019 CCJO, which maintained the central idea of global integration to guide the joint force in a strategic approach. The 2019 CCJO, while still the apex of joint concepts, is insufficient, as operational-level concepts such as the Joint Warfighting Concept (JWC), the Army’s multidomain operations conceptual work, and the Marine Corps’ Force Design 2030 are now past the substance of the 2019 CCJO.

Similarly, the U.S. Army published the Army Capstone Concept nested under the CCJO in December 2012. The central idea of the Army Capstone Concept was operational adaptability, meaning the Army understood the requirement to respond to a multitude of missions from humanitarian assistance to counterinsurgency to large-scale combat operations.2 Further, this strategic-level concept advanced the idea of the pivot to the Pacific by advocating for a rebalance of the force to the Asia-Pacific region.3 The concept then described three components of the central idea of prevent, shape, win; a strategic idea of how the Army would operate in campaigning through crisis and in conflict.4 With a strategic-level concept, the Army effectively provided a vision to the service on priorities and a focus of the force for the ensuing decade. However, since 2012, the U.S. Army produced additional operational-level or operating concepts without writing a new capstone concept.5

Today, the best example of strategic-level thinking in concepts is the U.S. Marine Corps’ Force Design 2030. This concept leads with the foresight and description of the overarching purpose of the Marine Corps. Through defining the strategic purpose, the Marines can better define its future force structure, enabling a divestment of current capabilities deemed no longer required for the future force.6 Force Design 2030 is a decisive measure by the Marine Corps. It is concept driven, and experiments and war games validate the conceptual work. It includes innovative ideas such as “stand in forces.”7 Force Design 2030 may be the best conceptual work since Gen. Donn Starry’s AirLand Battle.

In the July 2023 edition of Joint Force Quarterly, former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Gen. Mark Milley, introduced the JWC as the guiding light for the joint force. Throughout his article, Milley uses the German Wehrmacht in the interwar years as the ideal for military transformation, using the concept of blitzkrieg as the method for Germany overrunning Europe.8 The flaw in Milley’s analysis is the focus on the operational level. While he acknowledges the overwhelming might of the United States and its allies, he fails to consider that blitzkrieg worked in relatively smaller theaters of war. Further, strategic choices on the purpose and structure of the German armed forces led to its ultimate demise; centering a military on the survival of a political regime bent on genocide and world domination is not the best strategic choice for a military organization. The joint force must look beyond battlefield victory and avoid the fate of Germany’s Schlieffen Plan in World War I and the subsequent blitzkrieg in World War II.

Surprisingly, the best place to look during the interwar years for innovation is the United States and each of its services. The U.S. military, under the leadership of officers such as Gen. George Marshall, was able to link institutional preparedness to strategic and operational readiness. Marshall understood the necessity for large-scale infrastructure to support millions in uniform, and the requirements to conduct large-scale collective training and exercises before sending a drafted force into combat. Further, the strategic leadership of the American military was intellectually prepared through strategic-level wargames and the writing of strategic-level war plans such as the colored and rainbow plans.

The tenets of the JWC outlined in the Joint Force Quarterly article include such ideas as expanded maneuver, information advantage, resilient logistics, global fires, and pulsed operations.9 Achieving these tenets on a future battlefield will surely raise the chances of success for a joint force commander but is insufficient for thinking about the tenets of the future joint force at the strategic level. A strategic-level concept should broaden the aperture of tenets beyond victory in battle and center on how the joint force will attain victory in war to achieve the strategic ends of the Nation. The operational-level ideas presented in the JWC must connect to ideas that would lead to strategic victory and protection of the Nation’s enduring interests. Pulsed operations and global fires may destroy targets and win battles but will not by themselves win a war.

Historic Lessons

Focusing on initial battles at the operational-level war is a recipe for failure. The next strategic concept should offer ideas on how the joint force can enable victory over a sustained time frame. History suffers no shortage of examples where peer and near-peer adversaries come into conflict expecting a short war, only to be surprised when the war is not decided by Christmas. Examples include the Peloponnesian War to the Hundred Years War, the British and French wars in the late eighteenth century, the U.S. Civil War, the two world wars, the French and American wars in Vietnam, the Unted States in Iraq and Afghanistan, and, more recently, Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Napoleon was a master of tactics and operations, but his failure to understand the strategic level of war led to his downfall. Napoleon’s brilliance at the operational level led to a series of successes early in his reign. However, according to Sir Lawrence Freedman, Napoleon’s insistence on punishing former adversaries combined with his inability to form effective alliances or coalitions drove the French army into strategic defeat.10 Successful strategies are those that combine generalship with statesmanship.

Looking at the German army in the lead-up and fighting of World War II is a poor example to choose from for future concepts. While German innovation was effective at the operational level in a specific theater of war, the strategic purpose of the German military could never lead the nation to victory. Effective combined arms operations and air-to-ground coordination were certainly useful in winning battles, but designing an army to occupy foreign nations and exterminate populations, while using race, religion, and ethnicity as a method to exclude people from the ranks, was a surefire method to lose a war. A military built for tactical and operational success can still meet strategic failure.

Without the right strategic approach, winning a series of battles will not translate to victory. In his book The Allure of Battle, author Cathal Nolan describes what he calls “the illusion of short war.”11 One of his broad examples include Napoleon, who, according to Nolan, had a genius for the operational level of war but not the strategic. Napoleon did not center his strategy on coalition building, nor did he ever consider the broader impacts of a long war of attrition. Nolan then aptly describes how the Germans, in the lead-up to World War II, failed to learn the lessons of Napoleon, the four-year-long slog of the American Civil War, and the German strategic errors of the First and Second World Wars. As the Germans learned, fighting against the world on multiple fronts with nominal allies tends to be a poor strategic approach.

Major wars are not the only wars that tend to last longer than expected. The United States found itself in protracted wars in Vietnam in the 1960s, and in Iraq and Afghanistan in the first two decades of the twenty-first century. In these protracted wars, the U.S. Army was not prepared for a long-term fight and had to redesign its force structure from a division-centric force to a brigade-centric force. Moreover, to fight on two fronts for over a decade, the Army redesigned the composition of each brigade to create additional brigade combat teams that could be used as rotational forces in combat. The Army then split the brigade combat teams from organic division headquarters for respective deployments, complicating forward command relationships. This occurred during the peak of ground operations in Iraq and is one of the many ways the Army was unprepared for a prolonged war. These operational-level decisions occurred in a space where there was a dearth of coherent and unified strategic theories of victory.

A Strategic Concept

In Super Bowl LI, the Atlanta Falcons stormed to a 28–3 lead late in the third quarter only to fall to the New England Patriots in overtime.12 The Kansas City Chiefs won Super Bowl LVII on a last second field goal and again in Super Bowl LVIII with a touchdown in overtime.13 Like these football games, how wars end is more important and more impactful than how they begin. The joint force must look beyond the first battles and develop a strategic concept that carries the force in peacetime, through crisis and conflict, and onto victory in war. This strategic concept would describe a future strategic environment, the conditions of a future war, link the strategic level to the operational and the institutional levels of war, and most importantly be in the open for leaders throughout the joint force and the American public to discuss and iterate on.

Describing the anticipated future strategic environment is a critical part of any concept. As concepts tend to look out anywhere from ten to fifteen years in the future, an effective strategic concept would be enemy or adversary agnostic. While operational-level concepts that focus on battle can be orientated on specific adversaries, the next strategic concept should have the range to cover any adversary, not just the five problem sets of the current joint force.14 Overly focusing on a particular enemy can result in missed opportunities to succeed as the joint force reacts to real and perceived threats rather than being proactive and forcing adversaries into reaction mode. The farther one looks to the future, the more uncertain said future will be. A strategic concept developed in the late 1980s focused strictly on the Soviet Union would have wildly missed the mark, leading to its irrelevance.

In addition to describing the future strategic environment, an effective strategic concept will describe the purpose, roles, and composition of the future joint force. This description would detail the types of missions the joint force must be prepared to conduct ranging from large-scale combat operations to strategic deterrence, humanitarian assistance, day-to-day competing, and providing the Nation’s elected leadership with a range of options at the onset of a crisis. In detailing the composition of the joint force, a strategic concept would identify current trends on eligibility for service and the trends of a more diverse population in uniform.

There are historical lessons for a force failing to understand its central purpose or role, notably the Pentomic Army of the 1950s. During this time, the U.S. Army focused its efforts on nuclear war and an environment characterized by nuclear weapons and intercontinental ballistic missiles. With this environment as the central focus, the Army, according to Andrew J. Bacevich, moved away from its core task. Conventional warfighting capabilities were sacrificed in favor of high-altitude air defense and intermediate-range ballistic missiles.15 Misidentification or failing to identify a central purpose of the military or a service leads to a force unprepared for the next war.

Today’s operational-level focus of concepts often focuses on the major combat operations of a future war. Starry once described operational concepts as “a way to describe how you think you’re going to fight the war and then force the technology to produce the equipment, force the system to produce the organizations, force the training system to support training necessary to support the operational concept.”16 The prolonged wars in Iraq and Afghanistan display the failed logic of a focus on operational-level thought at the expense of all else, as postcombat operations proved to be the decisive phase of the war.17 Untested and unverified concepts such as shock and awe, rapid decisive operations, and effects-based operations, while sound in a vacuum, were unable to lead to a successful war termination.18 A strategic concept would consider and include all phases of a war from mobilization through major combat operations to postcombat and occupation.19 Operational-level concepts nested beneath should then focus on each individual phase.

An effective strategic-level concept would describe a strategic environment that considers the institutional aspect of the force. This strategic environment would also account for limitations imposed upon the joint force. For example, the joint force should recognize and forecast such institutional aspects like expected end strength; the organizational design of the force (will there be a cyber force?); and what education, training, and exercises will resemble. As joint concepts include input from each of the services, the benefits of a generally agreed-upon future strategic environment among the services would create coherence in capability development and force design.

The strategic environment would also account for limitations (what the joint force must and must not do) imposed upon the joint force. Fighting as part of a coalition is perhaps the most important element of strategy, arguably the most important limitation, and has been so since the Peloponnesian War.20 Moreover, since the First World War, the American way of war included allies and partners in each conflict. Former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Joseph Dunford characterized allies and partners as the joint force’s strategic center of gravity.21 For example, while senior military leaders tend to look for first-mover advantage in times of crisis and conflict, the nature of the U.S. political system favors an operational-level second move to gain and maintain strategic-level legitimacy. This legitimacy often aids in coalition building at the expense of an initial operational- or tactical-level advantages. This next strategic concept should include a centrality of allies and partners.

The next strategic concept should account for how the joint force will conduct a protracted war that lasts for months, to years, to decades. A war against a nation with advanced capabilities such as China will also mean a war against a nation that can reconstitute capabilities. This reconstitution will include manpower, as we are witnessing Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, and further include reconstitution of major air, land, maritime, and space combat platforms. As today’s concepts and strategies call for a force with greater lethality, there is a dearth of senior leaders calling for a joint force with more endurance.22 This endurance will include the reconstitution of capabilities to include the production of tanks, airplanes, and various munitions; the development of new software and other cyber capabilities; and the launch of new satellites and other space-based capabilities. A war against a near-peer or peer adversary will be a test of both endurance and long-term will.

Wars between great powers tend to be protracted wars. A concept that acknowledges a protracted fight would encourage service-level concept writers to consider the implications of how each service would contribute to this type of war. More than operational-level warfighting ideas, institutional ideas on manpower, personnel policies, and mobilization would emerge. These ideas could then undergo experimentation in the same way operational-level warfighting concepts undergo strict scrutiny. Acknowledging the institutional impacts and contributions to a future war can be just as decisive as the operational.

The professional development and education of leaders along with ideas on how the joint force can learn as a complex organization is a vital institutional piece of a strategic concept. The strategic environment is more than the geopolitical environment and the evolution of new and emerging technology. The intellectual capabilities of leaders at every echelon can define what nation has a decisive advantage in the future. Strategic concepts should address the necessity for joint force leaders to outthink and outplan future adversaries.23 Intellectual readiness can be the outcrop of solutions generated in a strategic concept.

An undervalued aspect of a strategic concept is the unclassified nature of the document. Just as the National Security Strategy serves as a tool of strategic communication, so should a strategic concept that describes the role of the U.S. military. An unclassified strategic concept serves as a message to all U.S. citizens, the men and women who will serve in the military, and America’s allies and partners. In a similar way, the initial Field Manual 100-5, AirLand Battle, served as a form of deterrence, communicating to the Soviets that the United States knew how to win, and a strategic concept would serve as a message to today’s enemies and adversaries that the U.S. military will be ready in the present and in the future.24

Conclusion

The power of concepts is how they force leaders to think about the future. The joint force must look beyond the operational level of war. This starts by ending the lionization of the Wehrmacht and German innovation in the interwar period. Idolizing a military that failed in war and led the world into a global conflagration, and whose purpose was to maintain a regime bent on genocide and world domination, is a worldview that must be put to rest. Should World War II be the example to look at for strategic-level thought, then the United States and its senior leadership in said war provides the best enduring example.

Future strategic concepts, however, do not have the luxury to assume that defeat in early battles is acceptable. When facing a peer adversary, and one who can outpace the joint force in manpower and industrial production, the operational level of war will maintain standing. Preserving the force while attriting enemy capabilities at the operational level will amplify or hasten victory just as failure at the operational level can hasten defeat. Thus, joint and service operational-level concepts necessarily must nest under overarching strategic concepts.

The joint force is on the path to operational excellence and strategic drift. The development and experimentation of operational-level concepts will certainly aid the joint force in winning battles but risks losing a war. War is more than the outcome of individual battles or the outcome of multiple battles, but the vision and ability to execute long-term operations even after the battle is won.

Notes

- Epigraph.

Donn A. Starry, “Operational Concepts and Doctrine: TRADOC Commander’s Notes No. 3, 20 February 1979,” in Press On! Selected Works of General Donn A. Starry, ed. Lewis Sorley, vol. 1 (Combat Studies Institute Press, 2009), 338.

- Joint Chiefs of Staff, Capstone Concept for Joint Operations: Joint Force 2020 (U.S. Government Printing Office, 2012), 1-2.

- U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) Pamphlet 525-3-0, The U.S. Army Capstone Concept (TRADOC, 19 December 2012), 11.

- Ibid., 6.

- Ibid., 11.

- New operational concepts include the 2014 Army Operating Concept, with the central idea of joint combined arms maneuver, and the more recent multidomain concept, which, as of 2024, is the Army’s operational approach to warfighting.

- U.S. Marine Corps, Force Design 2030 Annual Update (Department of the Navy, June 2023), https://www.marines.mil/Portals/1/Docs/Force_Design_2030_Annual_Update_June_2023.pdf.

- David H. Berger, A Concept for Stand-in Forces (Department of the Navy, December 2021), https://www.hqmc.marines.mil/Portals/142/Users/183/35/4535/211201_A%20Concept%20for%20Stand-In%20Forces.pdf.

- Mark Milley, “Strategic Inflection Point: The Most Historically Significant and Fundamental Change in the Character of War Is Happening Now—While the Future Is Clouded in Mist and Uncertainty,” Joint Force Quarterly, no. 110 (3rd Quarter, July 2023): 12, https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Joint-Force-Quarterly/Joint-Force-Quarterly-110/Article/Article/3447159/strategic-inflection-point-the-most-historically-significant-and-fundamental-ch/.

- Ibid.

- Lawrence Freedman, Strategy: A History (Oxford University Press, 2013), 71–75.

- Cathal J. Nolan, The Allure of Battle: A History of How Wars Have Been Won and Lost (Oxford University Press, 2017), 12.

- Associated Press, “Brady Leads Biggest Comeback, Patriots Win 34-28 in OT,” ESPN, 6 February 2017, https://www.espn.com/nfl/recap/_/gameId/400927752.

- Associated Press, “Super Bowl Magic: Mahomes, Chiefs Beat Eagles 38-35,” ESPN, 13 February 2023, https://www.espn.com/nfl/recap/_/gameId/401438030; Associated Press, “Patrick Mahomes Rallies the Chiefs to Second Straight Super Bowl Title, 25-22 Over 49ers in Overtime,” ESPN, 12 February 2024, https://www.espn.com/nfl/recap/_/gameId/401547378.

- The five problem sets of the department and the joint force include the People’s Republic of China as the pacing threat, Russia as the acute threat, and Iran, North Korea, and violent extremist organizations as persistent threats.

- Andrew J. Bacevich, The Pentomic Era: The U.S. Army Between Korea and Vietnam (Barakaldo Books, 2020), 102–11.

- Donn A. Starry, Press On! Selected Works of General Donn A. Starry, ed. Lewis Sorley, vol. 2 (Combat Studies Institute Press, 2009).

- Joel D. Rayburn and Frank K. Sobchak, The U.S. Army in the Iraq War, Volume I: Invasion–Insurgency–Civil War, 2003–2006 (Center of Military History, 2018), https://press.armywarcollege.edu/monographs/386/.

- Thomas K. Adams, The Army After Next: The First Postindustrial Army (Stanford University Press, 2008), 160.

- Ibid., 164.

- Freedman, Strategy, 3.

- Joseph F. Dunford Jr., “From the Chairman: Allies and Partners are Our Strategic Center of Gravity,” Joint Force Quarterly, no. 87 (4th Quarter, October 2017): 4–5, https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Media/News/News-Article-View/Article/1325218/from-the-chairman-allies-and-partners-are-our-strategic-center-of-gravity/.

- The so-called “ilities” have been a staple of concepts and strategies for a long time. Calling for more lethality, deployability, survivability, and sustainability often becomes the easy way out for strategic thinking.

- Mick Ryan, War Transformed: The Future of Twenty-First-Century Great Power Competition and Conflict (Naval Institute Press, 2022), 175.

- John L. Romjue, From Active Defense to AirLand Battle: The Development of Army Doctrine 1973–1982 (TRADOC, June 1984), 73, https://www.tradoc.army.mil/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/From-Active-Defense-to-AirLand-Battle.pdf.

Col. Dan Sukman is an Army strategist serving as an assistant professor at the Joint Advanced Warfighting School. He previously served as the chief of strategy development, Joint Staff J-5. He is the author of the book American Football and the American Way of War: The Gridiron and the Battlefield (Palgrave Macmillan, 2024).

Normandy

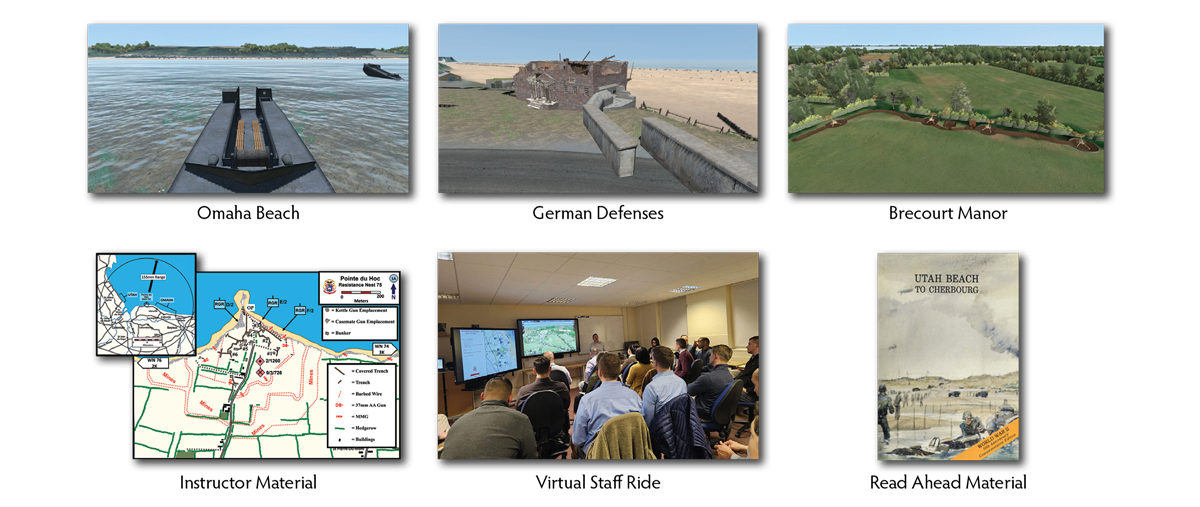

Virtual Staff Ride

Normandy virtual staff ride products are available for download from the Army University Press website. This study focuses on the American side of the invasion to include the airborne assault, Omaha and Utah Beaches, Pointe du Hoc, and a study on sustainment and the artificial harbors. Materials include instructor notes, participant read aheads, and the virtual terrain. These products will enable organizations with access to Virtual Battlespace 3 to conduct their own virtual staff ride or to conduct their own professional development sessions without the terrain.

To learn more about virtual staff rides, visit https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Educational-Services/Staff-Ride-Team-Offerings/

Back to Top