Got COIN?

Counterinsurgency Debate Continues

Article published on: 27 September 2018

Download the PDF

The counterinsurgency debate continues. For some, disappointments in Afghanistan and Iraq following the much-publicized release of Field Manual 3-24, Counterinsurgency, in December 2006 have called into question the relevance or validity of counterinsurgency doctrine. Counterinsurgent critics like retired Col. Gian Gentile claim that “population-centric counterinsurgency warfare has perverted a better way of American War which has primarily been one of improvisation and practicality.”1 In contrast, counterinsurgency advocates like Gen. David Petraeus and Lt. Col. John Nagl credit counterinsurgency early on for success during the Iraq surge.2 Both sides offer compelling arguments and yet miss the point—the argument is not the relevance of counterinsurgency but its implementation.

Insurgencies are a reality of international politics and have been for centuries. Between World War II and 2015, there were 181 insurgencies. They averaged over twelve years in duration, with a median of seven years. In some ways, the character of insurgent warfare during this period rapidly evolved because of technological advancements and other conditions.3 For example, insurgents have proven extremely innovative in achieving high levels of technical sophistication in manufacturing improvised explosive devises negating expensive state of the art countermeasures installed in combat vehicles.4 Insurgents’ media savvy is reflected using the Internet and social media to communicate, distribute propaganda, recruit individuals, and perform other activities to target audiences around the globe.5 Internet-based propaganda and tailored social media provided a way for the Islamic State to reach and inspire adherents to perpetuate attacks like the June 2016 shooting at an Orlando, Florida, nightclub.6 And insurgent warfare will continue to be the preferred adversarial military option for many nations in any future conflict with the United States and its allies; if history is any guide, this makes our involvement in such inevitable. Therefore, even as the U.S. Army transitions to multi-domain operations doctrine and training, it must capture counterinsurgency lessons learned from its conflicts over the last eighteen years to update and keep current counterinsurgency doctrine and policy for the next insurgency that is with great certainty coming.

Vietnam Counterinsurgency Failure Myth

Counterinsurgency critics often assert that the U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War is the prime example of a U.S. counterinsurgency failure. However, such an assertion is a fallacy for several reasons. Most historians of the Vietnam War fall into two schools of thought: those who believe that the United States failed to apply enough conventional pressure—military and political—on the communist government in Hanoi, and those who argue that the United States failed to use an appropriate counterinsurgency strategy. Both arguments have merit, but both ignore Hanoi’s strategy.7

It is important to remember that North Vietnam viewed the conflict as what is referred to today by some as a hybrid war, to be fought at the same time conventionally as well as unconventionally, with a supporting international informational and political component targeting U.S. popular opinion. As a result, the new and fragile Republic of Vietnam in the south faced a domestic insurgency supported by the North (guerrilla warfare by the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam [NLF]), a conventional invasion by Democratic Republic of Vietnam People’s Army of Vietnam (NVA) forces, and robust international informational and political opposition by a range of international actors who synchronized their efforts to undermine the South. To compound these challenges, the Republic of Vietnam was only five years old when North Vietnam decided to encourage armed resistance in support of opposition groups operating against the government led by President Ngo Dinh Diem at the same time it began infiltrating regular conventional forces with the support of Russia and China.

In anticipation of its ultimate objective of conquest, the NLF successfully conducted a campaign to replace local village leaders and officials throughout the Republic of Vietnam through assassination and intimidation. Consequently, the newly established government in Saigon found itself challenged on multiple fronts in countering both the NLF-led internal opposition while also battling conventional forces of the NVA.

However, in spite of the challenges, South Vietnam, relying heavily on U.S. support, was successful in fending off conquest by the North until the war was supposedly concluded with the Paris Peace Accords signed on 27 January 1973. At that point, the United States essentially abandoned further support of the South’s war effort. Of note, the final capitulation of South Vietnam was not due to a failed counterinsurgency effort but rather to a failed conventional effort to halt a military invasion during the conventional offensive and domestic uprising in the spring 1975.8

In contrast to the North’s hybrid strategy, President Lyndon Johnson and Gen. William Westmoreland did not support or emphasize counterinsurgency to oppose the South’s internal enemies but preferred large-scale, search-and-destroy conventional operations.9 In fact, Westmoreland saw the Marines’ use of civic action programs around Da Nang as a distraction from the main objective: the battlefield destruction of the NLF. Instead, Westmoreland insisted that the NLF would have to be defeated, and North Vietnamese infiltration halted before a proper civic action program could be instituted.10 As a result, the major focus of the U.S. effort was not on conducting counterinsurgency but on waging a conventional war primarily aimed at defeating the NLF and the NVA. The Vietnam War became viewed in the United States as a war of attrition between conventional armies and not one focused on garnering the support of the populace by winning hearts and minds.

On closer examination of the claims by counterinsurgency critics of the war, it is noteworthy that many such fail to acknowledge that there were significant successful counterinsurgency efforts in the Vietnam conflict. The Marine Corps Combined Action Program, the U.S. Army Special Forces Civilian Irregular Defense Group, and the Chieu Hoi program all achieved notable counterinsurgency successes during the Vietnam conflict. For example, U.S. Army Special Forces teams embedded themselves with the Montagnards, an isolated tribal people living in Vietnam’s central highlands, and soon were conducting effective operations with them against Viet Cong forces. In conjunction, Army Special Forces also trained other groups of “irregulars” such as the “Republican Youth” and the “Fighting Fathers”; each program experiencing significant success.11

The Chieu Hoi “Open Arms” Program was another example of a counterinsurgency program during the Vietnam conflict that achieved noteworthy successes while it existed. The program, established by Diem on 17 April 1963, was an offer of amnesty for members of the Viet Cong and the NVA who rallied to the government of Vietnam. Chieu Hoi had attracted more than 159,000 soldiers and members of the Communist Party when the Vietnam conflict concluded in April 1975. Chieu Hoi’s great achievements include the defection of Lt. La Thanh Tonc of the NVA, who provided the general battle plan of NVA forces and the order of battle for the attack to seize Khe Sanh. As a measure of success, captured Viet Cong documents indicated that the Viet Cong considered the Chieu Hoi program a serious threat and took extreme measures against their own cadre and fighters caught possessing Chieu Hoi leaflets or discussing the program.12

Contrary to the claims of critics, the lesson of U.S. involvement in Vietnam is not that counterinsurgency was a failed concept but that it failed because it was not properly and robustly implemented and integrated with conventional actions under the discipline of a clear overall strategy.

Counterinsurgency Lessons

There are several lessons learned from the Vietnam counterinsurgency effort that, when combined with lessons from previous counterinsurgency experiences and from our recent and ongoing counterinsurgency efforts, provide important insights into a viable approach to address current and future insurgencies. Fourteen key points highlighting such lessons are briefly discussed below.

There is no cookie-cutter approach. There is no single counterinsurgency approach to address all insurgencies. However, though each insurgency has a character of its own, there are recurring features among such conflicts from which common tested counterinsurgency practices can be distilled that will increase the likelihood of counterinsurgency success.

Insurgents have strategy options that can be generally described as conventional war, irregular war, and terrorism (targeted and collective punishment of civilians for the purpose of intimidation). These can be executed singly or in combination. As a result, the first important lesson is that counterinsurgency forces must tailor a specific approach to each insurgency that takes into account the unique features of each conflict together with the afflicted country’s available resources, its economic strength, the extent of the insurgency, etc.

Address grievances. Insurgencies occur for a reason, a simple but enduring feature that has been often overlooked in planning that merely focuses on militarily defeating an enemy in combat. Uniformly, insurgencies spring from unrequited grievances among some segment of the people. As a result, to defeat an insurgent movement, the reputed legitimate authority of a nation facing an insurgency must address and resolve the grievances of the citizen groups from whom insurgents are issuing. This is the most essential step to legitimize the authority of the counterinsurgent, which simultaneously undermines the legitimacy of the insurgents’ cause and leads to a loss of popular support for them.13

For example, to address peasant grievances over land ownership and distribution, the government of El Salvador attempted to implement agrarian reform as part of its counterinsurgency efforts in the 1980s to restructure the country’s unequal land tenure system, to improve local economies, and to undercut support for the insurgent Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN). However, opposition by the political right (many large landowners); bureaucratic inefficiency; and violence against agrarian reform officials by FMLN, paramilitary groups, and the coffee oligarchy undercut the public perception of the program as an insincere attempt to paper over one of the major grievances of many rural Salvadorans supporting the insurgency. This ultimately doomed the program and prolonged the conflict.14

Establishing legitimacy. Insurgencies develop where the ruling authority is regarded as illegitimate because it is perceived by the populace as being corrupt, abusive, lacking in control, and useless in providing security and/or services. Consequently, promoting the perception among the populace that the ruling authority has legitimacy is critical to counterinsurgency success; a country’s populace must perceive that its government and rulers have their best interests at heart. In conjunction, effective counterinsurgency practices emphasize successful efforts to delegitimize the insurgent movement in the eyes of the indigenous populace and international sympathizers by effective governance, even in the face of insurgent attacks.15

Limit influence of outsiders. Insurgencies that are not sponsored by external actors rarely endure for long. External actors are the enablers of final insurgent success, especially when not countered by a major external power supporting the counterinsurgency authorities and forces.

However, because sponsors of insurgency are usually foreign entities, counterinsurgent forces have an opportunity to exploit the involvement of any external actors supporting an insurgency. For example, British psychological warfare units were successful in publicly discrediting the insurgency in Malay as Chinese Communist inspired and supported. This facilitated counterinsurgent forces separating the Malay populace from the insurgents. Of note, this information campaign was executed in conjunction with relocating endangered villagers to guarded camps and expanding British patrols that denied sanctuary to insurgents.16

Similarly, counterinsurgents can also create or exploit fissures between insurgent groups and their outside supporters. This was true in the Democratic Republic of Congo insurgency during the late 1990s when Rwanda and Uganda switched their support for a Congo insurgent group led by Joseph Kabila.17

Support economic and social development programs. Development programs are key components of population-centric counterinsurgencies. Development programs demonstrate to the public the legitimacy of the sponsoring party and promote loyalty among the populace to the counterinsurgents’ cause. As a result, developmental projects cannot be stand-alone but must be part of a larger encompassing program designed to improve the security and quality of life of the targeted populace.

Successful development programs facilitate rapport with the population while undermining insurgent’s claims. However, development programs must be tailored to the realistic economic capabilities of the supported authority to provide them. Moreover, the programs must address the needs of the populace as the people identify the needs, not as deemed by the counterinsurgent force, and they must be sustainable. Unfulfilled promises produced by unsustainable programs that provide little actual long-term benefit are counterproductive, because they undermine faith in the counterinsurgency effort among the populace.

Also, counterinsurgent forces have the added responsibility of ensuring the safety of those participating in such programs. Increased reprisal actions by NLF participants in the Republic of Vietnam’s Strategic Hamlet Program highlighted the Republic of Vietnam’s inability to protect the citizens who participated in the program and its lack of sovereign control in many rural areas of the country.18

Protect and defend human rights. A root cause of many insurgencies can often be traced to government disregard for basic human rights. In such cases, insurgents will exploit perceived or real basic human rights or social injustice violations to attack the legitimacy and credibility of the ruling government and officials. For example, the NLF successfully exploited Republic of Vietnam President Ngo Dinh Diem’s persecution of Buddhists to undermine him domestically while garnering both national and international support against the Diem regime.19 Counterinsurgents must emphasize that their support for the continuing counterinsurgent effort is contingent upon respect for human rights both for citizens and captured enemies.

Provide amnesty for insurgents. Any hope for establishing stability following an insurgency requires an amnesty program for former insurgents to enable reintegration back into society. In a fairly recent example, failure of coalition and Afghan forces to grant amnesty to Taliban figures who abandoned the movement had repercussions far beyond the specific Taliban members targeted. Believing they lacked a role or place in the post-2001 Afghan society, many of these former Taliban members reached out to Taliban groups forming in Pakistan and rejoined the insurgency as a way of making a living.20

Achieve information operations dominance. In our age of instantaneous information transfer via the internet and social media, governments under attack and counterinsurgency forces battling an insurgency must gain information dominance over their adversaries. They must execute an aggressive and credible information operations strategy to shape attitudes and perceptions of the populace as well as foreign audiences in order to enhance the image of the government and its officials, counter insurgent propaganda, degrade morale and readiness of insurgent forces, and provide information on government policy and programs. Additionally, counterinsurgents must exploit insurgent excesses against the population, underscore insurgent support by foreign entities with their own agendas, and expose any inconsistencies between insurgent policy positions and their activities. Effective information strategies can also facilitate counterinsurgent forces gleaning potential intelligence from meaningful analysis of insurgent propaganda.

Intelligence plays a vital role. Intelligence is essential to counterinsurgency success. Counterinsurgent forces need to adapt their strategies, tactics, and security procedures necessary to collect intelligence, target insurgents, and disseminate information while executing counterinsurgency operations. Moreover, intelligence operations that help detect and thwart insurgent activities are the single most important practice in protecting a populace from threats to its security.21

Interact with the populace. Counterinsurgency forces need to find a way to interact with the local populace and refrain from hunkering down on bases.22 The Marine Corps Combined Action Program was a successful example of a counterinsurgency program that ensured security for the populace, undermined insurgents, empowered local and regional leaders and communities, and killed the enemy.23 Similarly, Navy Special Warfare Village Stability Operations programs were successful in stabilizing the southern Afghan province of Uruzgan.24

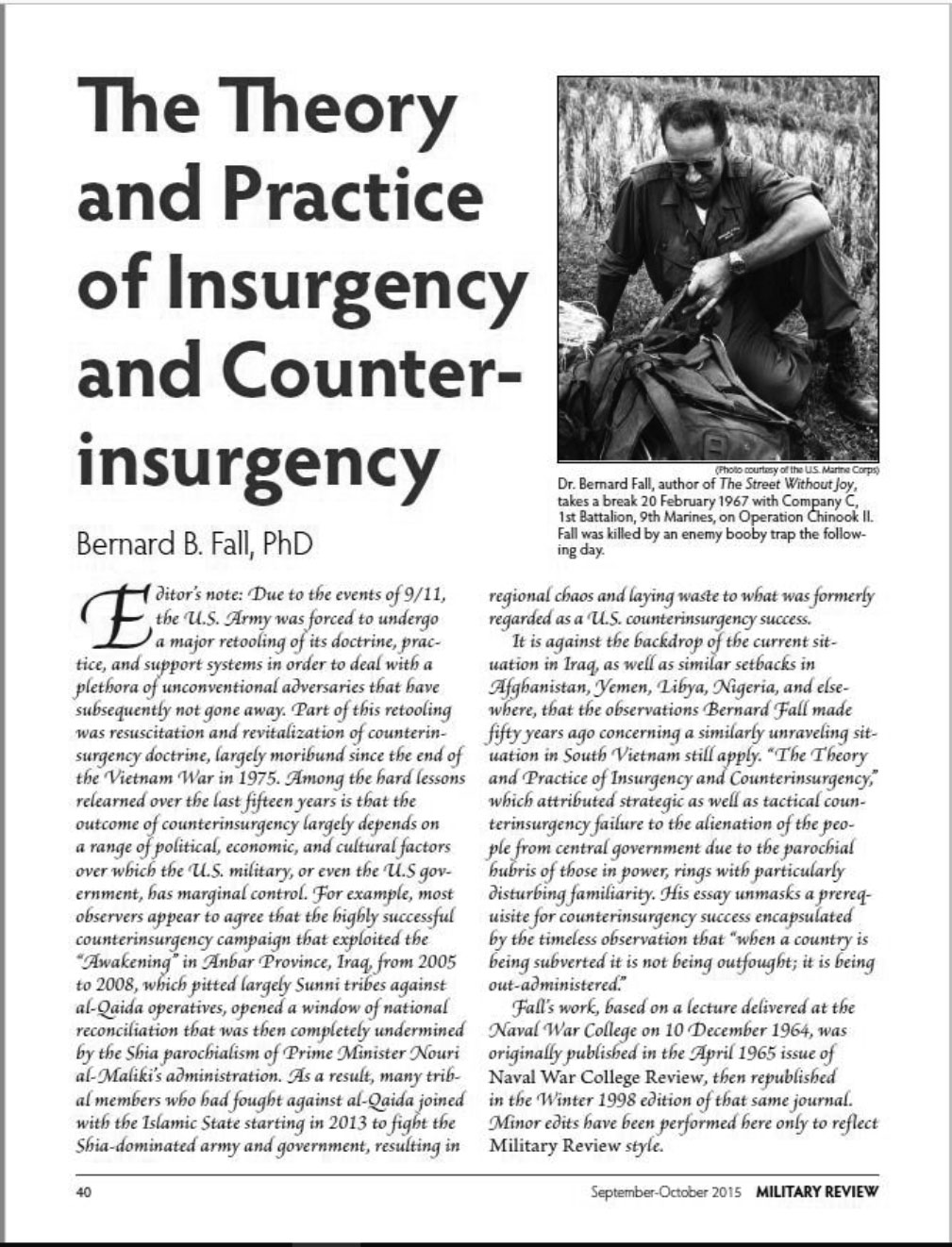

If you have interest in the relationship between governance and insurgency, Bernard B. Fall, professor of international relations at Howard University, conducted extensive field research throughout the 1950s and 1960 on the Cold War era conflicts unfolding then in Southeast Asia. His research chronicled and analyzed the expulsion of the French from their colonial control over Indochina and the gradual enmeshing of the United States in Indochina as it pursued policies aimed at stemming the expansion of Chinese-style communism.

Fall’s “The Theory and Practice of Insurgency and Counterinsurgency,” based on a lecture he delivered at the Naval War College on 10 December 1964, was originally published in the April 1965 issue of Naval War College Review. In this article, Fall coined the now often repeated aphorism related to governance and insurgency: “When a country is being subverted it is not being outfought; it is being out-administered.” He was among the first to predict the failure of the United States in its prosecution of the war in Vietnam because of what he noted were tactics formulated without an understanding of the societies in which the conflict was being fought. To view this reprinted article featured in the September-October 2015 edition of Military Review, visit https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Journals/Military-Review/English-Edition-Archives/2015-Archive/#sepoct.

Promote popular ownership of the counterinsurgency effort. The populace of a nation experiencing an insurgency must eventually take the lead role in defending itself if counterinsurgency operations are to be both successful and sustainable. Too often, the U.S. counterinsurgents have viewed the populace as a neutral or a third party to the conflict, when in reality, the members of the population are actually the key players. Village Stability Operations Programs in Afghanistan’s Special Operations Task Force—Southeast were successful in wrestling control away from the Taliban through effective recruiting of local Afghan police and coordinating their efforts with various government and security forces factions. The Afghans themselves became responsible for providing their own security.25

This demonstrates why counterinsurgent forces must avoid assuming responsibility for duties normally performed by local and regional governments. Counterinsurgent forces need to focus their efforts on targeting insurgent forces and inculcating into local law enforcement a sense of responsibility for policing, security, and other security-related programs. The intent is to enhance and consolidate local governing capabilities to ensure the sustainability of these capabilities once counterinsurgent forces leave the area.

Know the insurgent. One of the common failures of counterinsurgency practitioners is failing to make an effort to understand insurgents. A repeating feature of failed U.S. counterinsurgency efforts has been that they were inward-directed, concerned more with perfecting kinetic operational tactics, techniques, and procedures rather than seeking to understand the insurgent groups they faced, to include understanding their motivations, capabilities, and vulnerabilities at a social level. Any counterinsurgency efforts will have limited if any lasting success, no many how many high-value targets are killed or captured, without understanding the political, economic, social, and psychological motivations of insurgent groups and their members.26 Thus, successful counterinsurgency forces must emphasize gaining a sophisticated and nuanced understanding of the insurgents they face in order to develop viable options and effective countermeasures aimed at successfully ending an insurgency.

Insurgents and guerrillas attack where you are weak. The preferred targets for irregular insurgency and guerrilla warfare will remain soft rear-area targets. Guerrillas and insurgents characteristically shy away from set-piece battles. One example in the modern era, apart from Vietnam, is the Pohang Guerrilla Hunt during the Korean War, when groups of (North) Korean People’s Army soldiers infiltrated U.S. lines of communication to cut communications and harass rear installations.27

Earlier, sixty-to-eighty thousand Soviet partisans were successful in attacking German rail lines, cutting wire communications, laying field mines, and forcing the German army to dedicate combat forces to battle the partisans instead of Soviet forces.28 German planners’ flawed assumptions concerning the partisans concluded that the campaign against the Soviets would be four months long and so made no provision for such unforeseen contingencies as partisan attacks in their immediate rear areas and the protection of their lines of communication. Apparently, they simply could not conceive of such a thing as a resistance movement that targeted their lines of communication.

Be patient during multi-domain operations. As the Army transforms to fighting the multi-domain fight, it has an opportunity to incorporate valuable counterinsurgency lessons learned, both positive and negative, to improve counterinsurgency doctrine and policy. In counterinsurgency, the insurgents and guerrillas will avoid massing as well as force-on-force engagements. As a result, there may be no opportunity for decisive action or battle, and the conflict may be fought in indirect ways such as in the information realm. In the latter circumstances, it is important to keep in mind that trained, experienced personnel are required to execute successful counterpropaganda measures, and that patience is required since the results of counterpropaganda efforts must be conducted over a long period and may not be known for some time.

Conclusion

Insurgency has been the most prevalent form of armed conflict in the world since the late 1940s.29 Despite that fact, following the Vietnam War and through the remainder of the Cold War, the U.S. military establishment turned its back on counterinsurgency, refusing to consider operations against anything other than a “less-included case” for forces structured for and prepared to fight two major theater wars.30

However, after 9/11, insurgency returned to prominence as the Army was compelled to revisit the history of counterinsurgency doctrine as it ramped up for the conduct of insurgent conflicts in Iraq, Afghanistan, the Philippines, and elsewhere. As counterterrorism expert William Rosenau notes, “insurgency and counterinsurgency … have enjoyed a level of military, academic, and journalistic notice unseen since the mid-1960s.”31

As the pendulum of Army interest now swings away from interest in insurgency, the intent of this article is to promote discussion on the wisdom of continuing to include counterinsurgency lessons learned in Afghanistan and Iraq in updates to joint and Army doctrine as well as in counterinsurgency-related publications. Though counterinsurgency is never a replacement for strategy, the ends of counterinsurgency remain consonant with the concept of victory: to end the insurgency and return society back to a stable environment.

In the age of emerging multi-domain doctrine, perhaps the greatest lesson of our ongoing eighteen-year old conflict is that it should not be purely population-centric or insurgent focused but a hybrid of the two based on the nature of the insurgency. Sir John Bagot Glubb, British soldier, scholar, and author, underscored the essence of properly conceived counterinsurgency when he remarked, “The only way to defeat guerillas is with better guerillas, not by the methods of regular warfare.”

Notes

- Gian P. Gentile, “A Strategy of Tactics: Population-centric COIN and the Army,” Parameters 39 (Autumn 2009): 5, accessed 31 August 2018, https://ssi.armywarcollege.edu/pubs/parameters/articles/09autumn/gentile.pdf.

- Bryan Riddle, Essence of Desperation: Counterinsurgency Doctrine as the Solution to War-Fighting Failures (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2018), 103.

- Seth G. Jones, Waging Insurgent Warfare: Lessons from the Viet Cong to the Islamic State (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 5.

- Ibid., 6.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 7.

- Dale Anrade, “Westmoreland Was Right: Learning the Wrong Lessons from the Vietnam War,” Small Wars & Insurgencies 19, no. 2 (2008), accessed 31 August 2018, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09592310802061349?src=recsys.

- Kennedy Hickman, “Vietnam War: End of Conflict 1973-1975,” ThoughtCo, last updated 17 March 2017, accessed 31 August 2018, https://www.thoughtco.com/vietnam-war-end-of-the-conflict-2361333.

- Leo J. Daugherty III and Rhonda L. Smith-Daugherty, Counterinsurgency and the United States Marines Corps: Volume 2, An Era of Persistent Warfare, 1945-2016 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2018), 32.

- Ibid., 160.

- Ibid., 138.

- Herbert Friedman, “The Chieu Hoi Program of Vietnam,” Psywarrior, accessed 31 August 2018, http://www.psywarrior.com/ChieuHoiProgram.html.

- William Rosenau, “Counterinsurgency: Lessons from Iraq and Afghanistan”, Harvard International Review 31, no. 1 (Spring 2009): 52-56, accessed 31 August 2018, http://www.jstor.org/stable/42763272.

- Brian D’Haeseleer, The Salvadoran Crucible: The Failure of US Counterinsurgency in El Salvador, 1979-1992 (Lawrence, KS: The University of Kansas Press, 2017), 84–87.

- Steven Metz and Raymond Millen, Insurgency and Counterinsurgency in the 21st Century: Reconceptualizing Threat and Response (Carlisle Barracks, PA: United States Army War College, Strategic Studies Institute, November 2004), 26, accessed 31 August 2018, http://ssi.armywarcollege.edu/pdffiles/pub586.pdf.

- Jones, Waging Insurgent Warfare, 193–94.

- Ibid., 201.

- Mervyn E. Roberts III, The Psychological War for Vietnam 1960–1968 (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2018), 88-90.

- Ibid., 82–91.

- Benjamin P. McCullough, “Counterinsurgency in Afghanistan: A List Ditch Effort to Turn around a Failing War” (master’s thesis, Wright State University, 2014), 24, accessed 31 August 2018, https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2562&context=etd_all.

- Kalev I. Sepp, “Best Practices in Counterinsurgency,” Military Review 85, no. 3 (May-June 2005): 9.

- Jones, Waging Insurgent Warfare, 189.

- Daugherty and Smith-Daugherty, Counterinsurgency and the United States Marines Corps, 209–12.

- Daniel R. Green, In the Warlord’s Shadow: Special Operations Forces, the Afghans, and Their Fight against the Taliban (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2017), 213–38.

- Ibid., 213–20.

- Rosenau, “Counterinsurgency: Lessons from Iraq and Afghanistan,” 54–55.

- Daugherty and Smith-Daugherty, Counterinsurgency and the United States Marines Corps, 114–16.

- Edgar M. Howell, Department of the Army Pamphlet 20-244, The Soviet Partisan Movement, 1941-1944 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, August 1956), 203–13.

- Green, In The Warlord’s Shadow, 190.

- Christopher Paul et al., Paths to Victory: Lessons from Modern Insurgencies (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation 2013), xi.

- Ibid., xvii.

- Jones, Waging Insurgent Warfare, 190.

Lt. Col. Jesse McIntyre III, U.S. Army, retired, is an assistant professor at the U.S Army Command and General Staff College. He holds a BA from the University of Missouri and an MA from Touro University. He served as the director for psychological operations policy, Office of Assistant Secretary of Defense for Special Operations/Low Intensity Conflict; as a psychological operations officer on the Department of the Army staff; and in a variety of special operations and infantry assignments. He also instructed at the U.S. Army John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School.

Back to Top