Financial Access Denial

An Irregular Approach to Integrated Deterrence

Col. Sara Dudley, U.S. Army

Lt. Col. Steve Ferenzi, U.S. Army

Maj. Travis Clemens, U.S. Army

Download the PDF

Wake-up call to a hypothetical 2028: China makes good on its promise to “reunify” with Taiwan—by force. A U.S.-led coalition attempts to repel the invasion, but quickly discovers its operational reach is woefully inadequate to defend Taipei. The United States barely maintains notional access to critical seaports, airports, and canals across the globe—China owns them all. China’s seemingly “no strings attached” aid and infrastructure investments appeared advantageous to U.S. partners, especially when orchestrated by corrupt state officials. But over time, Beijing’s coercive gradualism cemented control over strategic power projection points across the Middle East, South America, and Africa. Without global access and basing, logistics—the backbone of U.S. combat power—slows to a crawl. China meanwhile achieves its reunification fait accompli.

Military Competition—More Than Traditional Warfighting

As a modern fighting force, the U.S. Army struggles with understanding and articulating what it does to “compete” beyond security assistance, combined exercises, and force posture.1 Unfortunately, our adversaries do not, as they masterfully integrate economic statecraft with military coercion to advance their interests in the gray zone short of war.2 Economic statecraft is a critical adversary capability allowing access to targeted states, but its associated corruption is an exploitable vulnerability.3 Military finance capabilities must complement traditional warfighting to capitalize on this liability to expand the U.S. coercive arsenal—fully integrated with interagency partners in the Departments of Treasury, Commerce, and State.

Reenvisioning and employing counterthreat finance (CTF) as a military competition activity against China and Russia to deny financial access to and influence over U.S. partners and allies offers an irregular way to strengthen “integrated deterrence”—the cornerstone of the 2022 National Defense Strategy (NDS).4 Expanding current CTF constructs to include considerations of friendly force financing and understanding the totality of the fiscal and economic environments allows more robust CTF efforts to protect against unwitting support to adversary proxies, corrupt powerbrokers, and state-owned enterprises. Clarity in this unique financial common operating picture would enable broader U.S. statecraft in a truly integrated fashion as Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin envisions.

A holistic CTF approach to competition—built upon lessons from the decades-long counterterrorism struggle, offers the Army sustainment, military intelligence, and special operations communities a new way to support the geographic combatant commands. This represents a tangible next step, since sustainment support currently utilizes contracting as a significant part of setting the theater.5 Different from the current Logistics Civil Augmentation Program, such an approach would provide an expanded range of options to complement more escalatory measures short of war such as blockades.6

To support the denial of adversary financial access and influence, the Army should employ CTF as a proactive competition activity with defensive and offensive components. This requires a fiscal preparation of the environment—whereby financiers conduct economic risk assessments, apply antimoney laundering/countering the financing of terror (AML/CFT) compliance structures, and inform planning to prevent funds from reaching proxy support, criminal, or patronage networks. In concert, financiers and Army special operations forces (ARSOF) working in crossfunctional teams disrupt and dismantle these networks.

Counterthreat Finance (Un)Defined

Threat finance is a broad term inclusive of the financing methods used by terrorists, criminals, and adversary states.7 For the U.S. Defense Department (DOD), threat finance specifically incorporates “illicit networks that traffic narcotics, weapons of mass destruction, improvised explosive devices, other weapons, persons, precursor chemicals, and related activities that support an adversary’s ability to negatively affect U.S. interests.”8

Unfortunately, this dated 2010 definition underemphasizes the adversarial role of states—especially in strategic competition today, and it is silent on addressing that the DOD may be a primary source of adversary revenue. The most significant gap, however, is neglect of the legitimate but coercive use of economic statecraft that epitomizes the Chinese and Russian approaches.9

New Fronts of Coercion through Economic Statecraft

Economic statecraft entails the use of economic means to achieve a foreign policy goal. Examples include trade policy, financial structures, private business, currency manipulation, and influence over state-owned enterprises (SOEs). With malign intent, a state can use these mechanisms to pressure a foreign government to the point of severe damage to its economy. Alternatively, a state can incentivize the targeted government to adopt policies that support its goals.10

China pursues economic statecraft by leveraging trade and investment dependencies, providing financial aid to key individuals and institutions willing to support its interests, and mobilizing SOEs to accomplish Beijing’s goals.11 Specifically, China uses its signature “Belt and Road Initiative” (BRI) to exploit massive infrastructure investments, such as roads, railways, ports, and electronic communications, in vulnerable countries. BRI serves as a mechanism not only for China to gain access to key political leadership around the world and shape their behavior, but also to control critical infrastructure and infiltrate or hijack communications networks and surveillance systems.12

Sri Lanka is one such example. In the lead up to Sri Lanka’s January 2015 election, the China Harbor Engineering Company provided over $7 million in campaign funding to incumbent President Mahinda Rajapaksa. This company was building the controversial port at Hambantota—which happens to be in Rajapaksa’s home district and a project he supported. Even though Rajapaksa lost, Sri Lanka also defaulted on its loans in 2016 and ceded control of the port to the China Merchants’ Port (a partial SOE) for ninety-nine years. The port construction provided China a vector to influence the Sri Lankan elections, as well as strategic infrastructure to support its navy.13

Russia similarly pursues economic statecraft by manipulating regional energy dependency, aiding militia and criminal organizations, and mobilizing the Russian diaspora in targeted countries.14 The former includes threatening price hikes and supply disruption of Russian gas and oil, and actual cuts of energy supplies for political purposes. The latter includes efforts to build business and media relationships, penetrate official organizations, and resource armed proxies. The April 2010 Russian-Ukrainian Kharkiv agreement exemplifies Russia’s economic preparatory approach—setting conditions for its annexation of Crimea in 2014 by allowing the Russian Black Sea Fleet to remain stationed in Sevastopol until 2042 in exchange for a significant price reduction of Russian natural gas.15

To help deny Chinese and Russian financial access, the Army must employ a new CTF construct. The international architecture in which the Financial Action Task Force (a money laundering and terrorist financing watchdog group) and international financial intelligence units handle risk, detection, and enforcement of Bank Secrecy Act requirements toward AML/CFT represents an underutilized model that military finance and comptroller professionals ought to apply when considering vendors. The generation of a similar risk-based vetting infrastructure and a cadre of professionals focused on identifying and denying adversary access to friendly force funding would provide mechanisms to compete with such actors. Evolving the way the Army approaches setting the theater is the ideal place to foster this change.

Setting the Theater—An Old Mindset for Yesterday’s War

As one of the Army’s five core competencies, setting and sustaining the theater “is essential to allowing the joint force to seize the initiative while restricting an enemy force’s options.”16 Setting the theater includes establishing access and infrastructure to support joint force operations. The Army supports the geographic combatant commands through its Army Service component commands (ASCCs)—the theater armies such as U.S. Army Pacific—as part of its Title 10, Army support to other services, and executive agent responsibilities.

The traditional approach to setting the theater focuses on large-scale combat operations. As Army doctrine states, “the purpose of setting a theater is to establish favorable conditions for the rapid execution of military operations and the support requirements for a specific OPLAN [operation plan] during crisis or conflict.”17 To fulfill this requirement, the Army maintains capabilities that include “intelligence support; communications; port and airfield opening; logistics; ground-based air defense; chemical defense; and reception, staging, onward movement, and integration.”18

Contract support and finance within the sustainment function both play a significant role.19 The newest manual on sustainment operations discusses operational contract support (OCS), “the process of planning and executing contract support during contingency operations,” and banking and disbursing, the “financial management activities ranging from currency support of military operations … to strengthening local financial institutions.”20 However, it only briefly considers operational security that involves vendor use of local nationals that may report information on friendly forces.

A stronger case for the theater army’s central role in deterrence rests in its partner engagements, information advantage, and sustainment activities through an active campaigning approach to shape the environment.21 Unfortunately, this is still a minority view. A framework for setting the theater must go beyond enabling access and sustainment primarily for armed conflict to one that explicitly includes denying financial access to adversaries through CTF as part of a comprehensive integrated deterrence toolkit.

Asymmetrically Setting the Theater—A New Mindset for Integrated Deterrence Today

A CTF approach to setting the theater should confront this challenge through the lens of coercion—the ability to influence an actor to do something that it does not want to do. The renowned scholar Thomas Schelling described coercion as encompassing two basic forms: deterrence and compellence. Deterrence reinforces status quo behavior by preventing a target from pursuing unwanted actions, while compellence intends to change a target’s behavior.22 The 2018 NDS emphasized how revisionist powers “increased efforts short of armed conflict by expanding coercion to new fronts,” while the new 2022 NDS elevates “integrated deterrence” to its primary line of effort.23 The Army must think about coercion in new ways—specifically irregular deterrence, to keep pace (see figure 1).24

Most examinations of the U.S. military’s contribution to coercion tend to focus on demonstrations of commitment (forward-stationed forces and security assistance); enforcing international law in the global commons (shows of force such as freedom of navigation operations); and limited uses of lethal force (precision airstrikes).25 Such studies do not include economic or financial measures beyond support to sanctions.26 This new approach expands options whereby the Army can contribute to general deterrence by denying adversary financial access to theater resources, as well as adding to a whole-of-government escalation ladder that better links the military with economic and financial instruments during crisis management.27

Classic deterrence, backed by large conventional formations and nuclear weapons, relies on signaling the power to hurt an adversary if it crosses a red line.28 Deterring gray zone coercion exercised through economic statecraft instead requires new ways to address the vulnerabilities that Russia and China exploit in targeted states.29 Counterthreat finance provides a mechanism of “irregular deterrence” through financial access denial, which works along the logic of making the target (corrupt politicians, local businesses, criminal organizations, etc.) too difficult, or costly, to purchase and leverage.30

Counterthreat finance would cover the full spectrum from general defensive actions to protect against U.S. and partner money inadvertently funding adversaries through OCS (e.g., vendor threat mitigation), to offensive operations—specifically in the information environment against nodes in adversary funding streams. Reframing the traditional CTF approach to “deny” illicit actors’ financial flows in terms of defensive and offensive operations broadens assurance that funding does not reach adversary networks and decreases the effectiveness of economic coercion (see figure 2.)31

Preventive Measures: Enabling Partner Financial Resilience in the Army Service Component Commands

Current efforts toward CTF primarily focus on financing used to engage in terrorist activities and support illicit networks. Targeted networks deal with trafficking narcotics, weapons of mass destruction, improvised explosive devices, weapons, and related material that support malign activity.32 Transnational organized crime, often coordinating and facilitating those activities, also demands attention from this same community of action. The reenvisioning of CTF into a broader context requires understanding the “denial” of financing within a broader prevention-disruption framework that moves beyond the “deny, disrupt, destroy, or defeat” description in existing doctrine.

The goal of preventing funds from reaching adversarial networks is to enable financial resilience—hardening against adversarial economic coercion. When considering the need to prevent friendly force sustainment funds from reaching illicit actors, the financial operating environment weighs heavily on planners and financial forces. The application of financial risk assessments and AML/CFT-like compliance structures within financial units making payments provides a twofold benefit. First, additional vetting and economic awareness provide more assurance to prevent U.S. funding spent in OCS from reaching criminal, corruption, or patronage networks, while secondarily supporting positive local economic outcomes.

To empower this full spectrum of financial and economic considerations, a “fiscal preparation of the environment” produces a picture of financial and economic conditions within a geographic area (see figure 3).33 This preparatory and ongoing running estimate provides the foundation of an expanded CTF.

Fiscal Preparation of the Environment

The fiscal preparation of the environment starts by defining the known fiscal and economic operating environment. This preparatory research step provides the underlying information to assess the situation and determine required controls to mitigate risk in financial transactions. General parameters parallel the AML/CFT risk assessment that a financial institution would do across risk categories within a compliance cell. The Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council manual outlines elements within specific risk categories of products, services, customers, entities, transactions, and geographic locations.34 Minimum military equivalent considerations for finance units would entail detailed research of the following: geographic risk affiliated with local banking systems, underlying societal value transfer systems, known black market or prominent illicit businesses, and identification of sanctioned or restricted companies or individuals.

These steps facilitate the production of financial templates and overlays to support decision making in a commander’s area of operations. These templates would outline vetted vendors, existing local AML/CFT law enforcement and policy, the international status of local banks, cash management policy, approved digital payment platforms, and the expected U.S. force density, contract support requirements, and capabilities.

Shaping the Fiscal Operating Environment

Clarity of economic conditions within high-risk AML/CTF areas prone to illicit actor manipulation informs planning to generate a more conducive economic environment. Shaping the fiscal operating environment utilizes the identified vulnerable portions of economies to inform how external fiscal or economic manipulation could generate effects on operations.

Commander visualization tools of financial effects on environmental variables (PMESII-PT) and cultural considerations (ASCOPE) should amplify understanding of the ground force position and relative fiscal advantages.35 Identification and mapping of U.S. and partner funding authorities, estimates of local contracting capability and civil considerations, and identification of AML/CFT risk particular to the local area round out this area of the spectrum. Finance and intelligence elements then use this analysis to present risk mitigation controls to the commander for CTF action based on his or her level of risk tolerance.

This analysis translates to an ability to tease apart contingency planning captured primarily as a military component of national power from substantial economic components that also exist. Given the size and scope of global U.S. military engagements, figuratively, a little “e” resides within the big “M” of DIMEFIL.36 Focusing solely on the lethal employment of the military (M) negates the opportunity to influence competition via contract dollars (little e) that commanders will spend in support of operations anyway. Smartly applying contract dollar requirements allows the military to foster partner nation fiscal resilience and enable actions appropriate for interagency partners.37

Disruptive Measures: Going on the Offense in the Theater Special Operations Commands

Offensive operations by the SOF community round out efforts toward financial access denial. Working as crossfunctional teams through the theater special operations commands (TSOCs), finance corps professionals and ARSOF can disrupt and dismantle critical corruption networks supporting Chinese and Russian interests. The intersection of CTF and special operations, especially civil affairs and psychological operations forces, can be most effective in the information environment. SOF serve several critical roles that enable CTF, ranging from civil reconnaissance to precision messaging and enabling the reach of national authorities through interagency partners.

Imposing Costs on Infrastructure Investments

In a reconnaissance role, a SOF civil affairs team acting as a civil military support element (CMSE) can maintain relationships in strategic areas through which they can observe Chinese economic activities and their effects. New construction sites or talks of contracts with Chinese investors are often topics broached during regular meetings and contacts. Civil reconnaissance allows the TSOCs to map BRI’s reach and apply targeted CTF measures against associated individuals and businesses facilitating China’s access.38 This includes serving as a tipping and cueing function to other agencies such as the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Asset Controls.

Resistance-focused efforts in conjunction with targeted CTF [counterthreat finance] measures could foster partner-nation will and political leverage against Russia’s efforts to sway its key leaders—denying financial access over time to reduce Russia’s position of advantage.

With an eye toward civil resilience, SOF can degrade the effects of adversary information operations on relevant populations that enable financial access.39 SOF supports working with legal and community organizations to better understand customs, licensing, or permit processes they should mandate and enforce to ensure their sovereignty. Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), especially environment-oriented ones, often have legitimate concerns over the negative effects of construction.40 Through U.S. embassy and NGO contacts, CMSEs can illuminate concerns of BRI projects to NGOs who have influence to sway the partner-nation to oppose these projects. As popular frustration continues to grow with unsustainable debt-for-infrastructure deals in developing countries along the BRI, influence campaigns could enable local and multinational partners to discredit Chinese activities and inhibit further predatory investments.41

Disentangling Energy Dependencies

Special operations forces can serve a similar function against Russia through relationships with U.S. embassies and partner-nation officials and civilian influencers. Russia creates a critical vulnerability for itself by leveraging energy exports to sway foreign governments. A decrease in demand would result in a decrease in Moscow’s political leverage.

Civil reconnaissance can identify vulnerable locations that hold outsized political influence in the partner-nation. That military information flow to the U.S. embassy would allow enhanced transparency and new value proposition for consideration in application of resources, perhaps through the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation, to establish alternative energy infrastructure for these specific cases. By targeting specific locations that produce the most public outcry during petroleum embargoes or price increases, the partner-nation can alleviate political pressure without changing the entire country’s energy infrastructure.

Special operations forces could also support resistance against Russian economic coercion by highlighting pipeline construction through environmentally sensitive areas or culturally significant regions. Resistance-focused efforts in conjunction with targeted CTF measures could foster partner-nation will and political leverage against Russia’s efforts to sway its key leaders—denying financial access over time to reduce Russia’s position of advantage.42

Illuminating and Supplanting the Funding Flows

Encouraging selectively introduced digital value-transfer systems may further insulate populations in coercion-prone areas. Special operations engagements, via training events and long-standing mil-to-mil relationships, could eschew Western-centric payment methods, normally in U.S. dollars, and adopt preexisting local digital payment platforms, endorse cryptocurrency payments, or offer access to a specialized decentralized application based on answering communal needs. New cryptocurrency technologies offer communities an efficient complementary mechanism to create “civic or city” currencies that support local economic development, societal cohesion, and active participation in the sustainability of local communities.43

The introduction of such digital payment mechanisms allows for distributed, resilient, and transparent value transfers that make it more difficult for China or Russia to engage in predatory economic practices. High societal adoption rates of open-source cryptocurrency technology allow analysis of where payments ultimately land and illuminate external injects of funding. SOF’s ability to rapidly prototype, test, procure, and deploy such technology provides an additional layer against operational sustainment payments reaching illicit actors, covert payments reaching corrupt local officials, the warping of local markets, or the generation of unsustainable economics.44 It also allows the United States and partners to compete against Chinese Digital Currency Electronic Payment (DCEP) and digital yuan, and Russian cryptocurrency (“CryptoRuble”) intended to cement adversary leverage and unseat the U.S. dollar.45

Cashing in on Finance as a System

Planners can optimize efforts toward comprehensive financial access denial through a systems framework that emphasizes cost imposition throughout the entire process. This addresses financial inputs (physical and virtual funding streams), conversion mechanisms (SOEs and corrupt government officials), and outputs (commercial infrastructure and proxy networks) (see figure 4).46 On the front end, this involves raising the costs of obtaining financial inputs and impeding conversion of that funding to outputs. On the back end, disrupting the outputs and blunting negative effects on the population set conditions to compel adversary behavior change and deter future attempts at coercion.47

Raise the costs of obtaining inputs. Informal money transfers take the form of hard currency exchanges, digital payment accounts not affiliated with banks, online exchange forums, and peer-to-peer cryptocurrency payments that circumvent traditional tracking systems. The difficulty in attacking these structures is identifying them in the first place. This is where SOF can support interagency efforts. Through normal engagements, CMSEs gain a broad understanding of how economic factors affect the local population and can identify the specific mechanisms, locations, and personalities involved in digital payments and online exchanges. Armed with this knowledge, CMSEs work with the U.S. embassies to leverage interagency tools. Applying compliance structures, risk-based vetting infrastructure, and stringent needs statements make it harder for those funds to reach their intended targets through OCS pipelines and analogous partner-nation processes.

Impede the conversion mechanisms. SOEs, corrupt government officials, informal power brokers, and local businesses provide the access, placement, and influence that China and Russia leverage for exploitation and coercion. Targeted vilification of corrupt officials and predatory commercial entities can illuminate malign actors. Psychological operations teams alongside CMSEs message through local media, social media, and in-person engagements about these corrupt officials—enabling strikes, protests, local democratic processes, and international pressure campaigns to remove them from office or positions of influence. Similarly, CMSEs can provide targeted information to aid restrictions on foreign engineers and expand contract cancelations, administrative legal hurdles, and litigation to persuade adversaries to cease their activities and alter their decision calculus.

Disrupt the outputs. The construction and maintenance of physical infrastructure and proxy networks serve as adversarial action arms. Outputs from infrastructure might also represent critical resources that allow adversaries outsized influence in global supply chains. Offensive measures such as asset seizures, cyber penetration, physical sabotage, arrests, and deportations expand the range of options to escalate when necessary.

Blunt the adverse effects on the population. Local communities, businesses, and workers often bear the brunt of adversarial economic coercion and its associated corruption, especially when it involves foreign labor, environmental damage, and loss of sovereignty.48 Mitigating these negative impacts through targeted worker compensation, local economic investments, micro loans, environmental protection measures, and increased community participation in economic decisions would complete the efforts to achieve financial access denial.

Money in the Bank, or Bad Investment?

Despite the clear benefits of pursuing a broadened CTF approach to competition, the interrelated issues of scope, scale, and capacity prevent CTF from becoming a silver bullet. Scoping competition CTF efforts to include illicit and corruption networks makes sense. However, expansion to include SOEs—the most powerful arm of China’s economic statecraft, raises questions about scale. Akin to multinational conglomerates, many SOEs have listings on several foreign stock exchanges. Comprehensive denial of SOEs through CTF alone is impossible without significant efforts from many international partners. However, the mitigation and disruption of in-country malign SOE activities, especially related to BRI, remains feasible.

The question of whether the Army Finance and Comptroller Corps and SOF communities have the capacity to employ CTF activities at the scale necessary to affect adversary decision calculus is also a valid concern. To date, the finance corps added CTF as a core competency, established pilot cells collocated with SOF, began incorporating financial analysis into theater-level training exercises, and established ad-hoc training programs from existing interagency offerings to jump-start the learning curve.

While the SOF finance professionals develop a prototype of the capability, the broader Army finance initiative must create dedicated development prototypes of dedicated service-level CTF career paths, mature the doctrine, and make force structure trade-offs to optimize its human capital toward long-term CTF success across the joint force. Integrating and leveraging the existing finance-related capabilities and authorities across the ASCCs and TSOCs with those of interagency partners offers outsized return on investment that decision-makers must not ignore.

Shareholder Equity through Full-Spectrum Counterthreat Finance

Deterring adversaries from exploiting vulnerable partners through financial vectors, as well as compelling behavior change to align with U.S. interests, requires new ways to affect their decision calculus in daily competition. Preventative and disruptive CTF measures provide one such way—through full integration of Army conventional forces, ARSOF, and interagency partners.

With the Army’s focus on multidomain operations, the theater army—as the ASCC for its assigned combatant command, is the principal Army formation “responsible for deterring or defeating an adversary’s malign influences and overt aggression below armed conflict within the theater.”49 Reconceptualizing how the Army sets the theater—specifically with an irregular CTF approach to deny adversary financial access, strengthens the Army’s contributions to integrated deterrence and expands the aperture of multidomain operations to the financial arena.

The CTF approach to deterrence also supports efforts to institutionalize irregular warfare lessons learned from past conflicts.50 Adapting CTF activities today against proxies, corrupt powerbrokers, and SOEs employed by China and Russia toward financial access denial would capture and build upon lessons from CTF in the decades-long counterterrorism struggle. Enhanced with intelligence fusion, the integration of ASCC and TSOC crossfunctional teams further advances the conventional and SOF integration, interoperability, and interdependence established over nearly twenty years of counterterrorism operations.51

Finally, money and financial flows do not recognize military and civilian bifurcations. While Chinese infrastructure spending through BRI is qualitatively and quantitatively different than threat finance in Iraq, adapting those tools and enhancing the scale and scope of interagency tools like those found in the Treasury and Commerce Departments could prove critical to deterring adversary gray zone behavior. Re-envisioned CTF will enable broader U.S. economic statecraft and help the DOD strengthen integrated deterrence through a comprehensive military irregular–conventional–nuclear deterrence triad. We cannot afford to forego this opportunity to change, or else risk moving closer to our own checkmate.

Notes

- James McConville, The Army in Military Competition, Chief of Staff Paper #2 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Publishing Office [GPO], 1 March 2021), accessed 19 September 2022, https://api.army.mil/e2/c/downloads/2021/03/29/bf6c30e6/csa-paper-2-the-army-in-military-competition.pdf.

- Kevin Bilms, “Gray Is Here to Stay: Principles from the Interim National Security Strategic Guidance on Competing in the Gray Zone,” Modern War Institute at West Point, 25 March 2021, accessed 14 September 2022, https://mwi.usma.edu/gray-is-here-to-stay-principles-from-the-interim-national-security-strategic-guidance-on-competing-in-the-gray-zone.

- Sara Dudley, Kevin Stringer, and Steve Ferenzi, “Beyond Direct Action: A Counter-Threat Finance Approach to Competition,” Kingston Consortium on International Security (April 2021), accessed 27 November 2022, https://www.thekcis.org/publications/insight-13; Jonathan Hillman, “Corruption Flows Along China’s Belt and Road,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, 18 January 2019, accessed 14 September 2022, https://www.csis.org/analysis/corruption-flows-along-chinas-belt-and-road.

- Katie Crombe, Steve Ferenzi, and Robert Jones, “Integrating Deterrence across the Gray—Making It More than Words,” Military Times (website), 8 December 2021, accessed 14 September 2022, https://www.militarytimes.com/opinion/commentary/2021/12/08/integrating-deterrence-across-the-gray-making-it-more-than-words/.

- Joseph Shimerdla and Ryan Kort, “Setting the Theater: A Definition, Framework, and Rationale for Effective Resourcing at the Theater Level,” Military Review 98, no. 3 (May-June 2018): 55–62, accessed 14 September 2022, https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Journals/Military-Review/English-Edition-Archives/May-June-2018/Setting-the-Theater-Effective-Resourcing-at-the-Theater-Army-Level/.

- Army Regulation 700–137, Logistics Civil Augmentation Program (Washington, DC: U.S. GPO, 2017), accessed 14 September 2022, https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/pdf/web/ARN2768_AR700-137_Web_FINAL.pdf. This regulation establishes a Department of the Army regulatory program outlining policies, responsibilities, and procedures for implementing the Logistics Civil Augmentation Program to provide full-spectrum logistics and base support services using economies of scale contracts for global contingencies.

- Dudley, Stringer, and Ferenzi, “Beyond Direct Action”; see also, e.g., Kevin D. Stringer, “Counter Threat Finance (CTF): Grasping the Eel,” Military Power Revue, no. 2 (2013): 64–70; Danielle Camner Lindholm and Celina Realuyo, “Threat Finance: A Critical Enabler for Illicit Networks,” chap. 7 in Convergence: Illicit Networks and National Security in the Age of Globalization, ed. Michael Miklaucic and Jacqueline Brewer (Washington, DC: National Defense University Press, 2012).

- Department of Defense (DOD) Directive (DODD) 5205.14, DoD Counter-Threat Finance (CTF) Policy (Washington, DC: DOD, 19 August 2010, incorporating change 3, 3 May 2017), https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodd/520514p.pdf.

- Dudley, Stringer, and Ferenzi, “Beyond Direct Action.”

- Travis Clemens, Special Operations Forces Civil Affairs in Great Power Competition, JSOU Report 20-4 (MacDill Air Force Base, FL: Joint Special Operations University Press [JSOU], 2020), 22, accessed 11 October 2022, https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/AD1131100.pdf.

- Thomas Mahnken, Ross Babbage, and Toshi Yoshihara, Countering Comprehensive Coercion: Competitive Strategies against Authoritarian Political Warfare (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, 30 May 2018), 36–37, accessed 14 September 2022, https://csbaonline.org/research/publications/countering-comprehensive-coercion-competitive-strategies-against-authoritar/publication/1.

- Will Doig, “The Belt and Road Initiative Is a Corruption Bonanza,” Foreign Policy (website), 15 January 2019, accessed 14 September 2022, https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/01/15/the-belt-and-road-initiative-is-a-corruption-bonanza/; Clemens, Special Operations Forces Civil Affairs in Great Power Competition, 59; Arjun Kharpal, “China’s Surveillance Tech Is Spreading Globally, Raising Concerns about Beijing’s Influence,” CNBC, 8 October 2019, accessed 14 September 2022, https://www.cnbc.com/2019/10/08/china-is-exporting-surveillance-tech-like-facial-recognition-globally.html; Katherine Atha et al., China’s Smart Cities Development (Vienna, VA: SOS International, January 2020), accessed 5 October 2022, https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/China_Smart_Cities_Development.pdf.

- Clemens, Special Operations Forces Civil Affairs in Great Power, 22.

- Mahnken, Babbage, and Yoshihara, Countering Comprehensive Coercion, 20–21.

- Wojciech Kononczuk, “Russia’s Real Aims in Crimea,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 13 May 2014, accessed 27 November 2022, https://carnegieendowment.org/2014/03/13/russia-s-real-aims-in-crimea-pub-54914.

- Army Doctrine Publication (ADP) 1, The Army (Washington, DC: U.S. GPO, 31 July 2019), 2-8.

- Field Manual (FM) 4-0, Sustainment Operations (Washington, DC: U.S. GPO, 31 July 2019), 3-1.

- ADP 1, The Army, 2-8.

- Shimerdla and Kort, “Setting the Theater,” 61.

- FM 4-0, Sustainment Operations, 5-13, A-9, A-11, A-43.

- Justin Magula, “The Theater Army’s Central Role in Integrated Deterrence,” Military Review 102, no. 3 (May-June 2022): 77–89, accessed 14 September 2022, https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Journals/Military-Review/English-Edition-Archives/May-June-2022/Magula/.

- Keith Pritchard, Roy Kempf, and Steve Ferenzi, “How to Win an Asymmetric War in the Era of Special Forces,” The National Interest (website), 12 October 2019, accessed 27 November 2022, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/how-win-asymmetric-war-era-special-forces-87601; see also Thomas Schelling, Arms and Influence (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008), 69–73; Tami Biddle, “Coercion Theory: A Basic Introduction for Practitioners,” Texas National Security Review 3, no. 2 (Spring 2020): 94–109, accessed 14 September 2022, https://tnsr.org/2020/02/coercion-theory-a-basic-introduction-for-practitioners/.

- Office of the Secretary of Defense, Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy of the United States of America (Washington, DC: DOD, 2018), 2, 5; Office of the Secretary of Defense, “Fact Sheet: 2022 National Defense Strategy” (Washington, DC: DOD, March 2022), https://media.defense.gov/2022/Mar/28/2002964702/-1/-1/1/NDS-FACT-SHEET.PDF.

- Graphic created by authors, based on material adapted from Barry Blechman and Stephen Kaplan, Force without War: U.S. Armed Forces as a Political Instrument (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 1978); and Joseph Nye, The Future of Power (New York: Public Affairs, 2011).

- Melanie Sisson, James Siebens, and Barry Blechman, eds., Military Coercion and U.S. Foreign Policy: The Use of Force Short of War (New York: Routledge, 2020), 16–50.

- Ibid., 50–56; Phil Haun, “Air Power, Sanctions, Coercion, and Containment: When Foreign Policy Objectives Collide,” in Coercion: The Power to Hurt in International Politics, ed. Kelly Greenhill and Peter Krause (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), 77–92.

- Integrating Deterrence Across the Gray, YouTube video, posted by “SMA Speaker Series,” 56:10, 20 January 2022, accessed 11 October 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rCs_WjwAvqY&t=1s; Elizabeth Rosenberg and Jordan Tama, Strengthening the Economic Arsenal: Bolstering the Deterrent and Signaling Effects of Sanctions (Washington, DC: Center for a New American Security, December 2019), 10, accessed 19 September 2022, https://s3.amazonaws.com/files.cnas.org/documents/CNAS-Report-Econ-Arsenal-final.pdf?mtime=20191210155831.

- Liam Collins and Lionel Beehner, “Thomas Schelling’s Theories on Strategy and War Will Live On,” Modern War Institute at West Point, 16 December 2016, accessed 19 September 2022, https://mwi.usma.edu/thomas-schellings-theories-strategy-war-will-live/.

- Pritchard, Kempf, and Ferenzi, “How to Win an Asymmetric War in the Era of Special Forces.”

- Michael Mazarr, Understanding Deterrence (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2018), 2, accessed 19 September 2022, https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/perspectives/PE200/PE295/RAND_PE295.pdf.

- Developed by Col. Sara Dudley, graphic by Col. David Vandevander.

- DODD 5205.14, DoD Counter-Threat Finance (CTF) Policy.

- Graphic created by a U.S. Army Finance Corps working group: Cols. Sara Dudley, Nicholas LaSala, and David Vandevander; Lt. Col. Krystyl Pillion; Maj. Joshua Lakey; and Capt. Jon Bobb.

- Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council, Bank Secrecy Act/Anti-Money Laundering Examination Manual (Arlington, VA: Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council, 2014), accessed 19 September 2022, https://bsaaml.ffiec.gov/manual.

- For an example of a PMESII/ASCOPE matrix, see Joint Publication (JP) 3-24, Counterinsurgency (Washington, DC: U.S. GPO, 25 April 2018), IV-6, accessed 19 September 2022, https://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/Doctrine/pubs/jp3_24.pdf; and JP 5-0, Joint Planning (Washington, DC: U.S. GPO, 16 June 2017), IV-11. PMESII–PT: political, military, economic, social, information, infrastructure–physical environment and time; ASCOPE: areas, structures, capabilities, organizations, people, and events. This construct of assessment developed by Capt. Jon Bobb in the finance corps working group.

- The Department of Defense considers the basic elements of national power: diplomacy (D), information (I), military (M), and economic (E) with additional instruments of power such as financial (F), intelligence (I) and law enforcement (L)—DIMEFIL.

- Robert Blackwell and Jennifer Harris, War by Other Means: Geoeconomics and Statecraft (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016), 223.

- Clemens, Special Operations Forces Civil Affairs in Great Power Competition, 65.

- Ibid., 87.

- Ibid., 65.

- Christopher Balding, “Why Democracies Are Turning against Belt and Road: Corruption, Debt, and Backlash,” Foreign Affairs (website), 24 October 2018, accessed 19 September 2022, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2018-10-24/why-democracies-are-turning-against-belt-and-road. For a fictional vignette of a Special Forces/civil affairs/psychological operations (PSYOP) cross-functional team operational control to Special Operations Command Africa (with reachback to the 8th PSYOP group’s information warfare center at Fort Bragg, North Carolina), disrupting Chinese economic activities in Africa, see 1st Special Forces Command (Airborne), A Vision for 2021 and Beyond (Fort Bragg, NC: U.S. Army Special Operations Command, August 2021), 12–13, accessed 19 September 2022, https://www.soc.mil/USASFC/Documents/1sfc-vision-2021-beyond.pdf.

- Clemens, Special Operations Forces Civil Affairs in Great Power Competition, 80; Dudley, Stringer, and Ferenzi, “Beyond Direct Action.”

- Beth Noveck and Victoria Alsina, “More Than a Coin: The Rise of Civic Cryptocurrency,” Forbes (website), 27 March 2018, accessed 19 September 2022, https://www.forbes.com/sites/bethsimonenoveck/2018/03/27/more-than-a-coin-the-rise-of-civic-cryptocurrency/#224c2d4f6b68.

- Sara Dudley et al., “Evasive Maneuvers: How Malign Actors Leverage Cryptocurrency,” Joint Force Quarterly 92 (1st Quarter, 2019), accessed 19 September 2022, https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/jfq/jfq-92/jfq-92.pdf.

- Danny Vincent, “One Day Everyone Will Use China’s Digital Currency,” BBC News, 24 September 2020, accessed 19 September 2022, https://www.bbc.com/news/business-54261382; Andrew Work, “China’s DCEP Will Be the World’s Sputnik Money Moment,” Forkast, 10 August 2020, accessed 19 September 2022, https://forkast.news/china-cbdc-digital-currency-e-rmb-launch-preview-andrew-work/; Helen Partz, “Bank of Russia Issues Consultation Paper on Digital Ruble,” Cointelegraph, 13 October 2020, accessed 19 September 2022, https://cointelegraph.com/news/bank-of-russia-issues-consultation-paper-on-digital-ruble.

- Graphic created by authors, adapted from framework developed by Nathan Leites and Charles Wolf, Rebellion and Authority: An Analytic Essay on Insurgent Conflicts (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 1970), 35, accessed 11 October 2022, https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/reports/2006/R0462.pdf.

- This construct builds on the systems framework developed by Leites and Wolf in Rebellion and Authority.

- Bradley Jardine, “Why Are There Anti-China Protests in Central Asia?,” Washington Post (website), 16 October 2019, accessed 19 September 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/10/16/why-are-there-anti-china-protests-central-asia/.

- U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) Pamphlet 525-3-8, The U.S. Army Concept for Multi-Domain Combined Arms Operations at Echelons above Brigade 2025–2045 (Fort Eustis, VA: TRADOC, 6 December 2018), 35, accessed 19 September 2022, https://adminpubs.tradoc.army.mil/pamphlets/TP525-3-8.pdf; see also FM 3-0, Operations (Washington, DC: U.S. GPO, 1 October 2022), 4-12–4-13, accessed 27 November 2022, https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/ARN36290-FM_3-0-000-WEB-2.pdf.

- Office of the Secretary of Defense, Summary of the Irregular Warfare Annex to the National Defense Strategy (Washington, DC: DOD, 2020), 3, accessed 21 November 2022, https://media.defense.gov/2020/Oct/02/2002510472/-1/-1/0/Irregular-Warfare-Annex-to-the-National-Defense-Strategy-Summary.PDF.

- Jason Wesbrock, Glenn Harned, and Preston Plous, “Special Operations Forces and Conventional Forces Integration, Interoperability, and Interdependence,” PRISM 6, no. 3 (December 2016), accessed 19 September 2022, https://cco.ndu.edu/PRISM-6-3/Article/1020999/special-operations-forces-and-conventional-forces-integration-interoperability/; FM 6-05, Multi-Service TTPs for Conventional Forces and Special Operations Forces Integration, Interoperability, and Interdependence (Washington, DC: U.S. GPO, 25 January 2022), accessed 27 November 2022, https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_d/ARN34466-FM_6-05-000-WEB-1.pdf.

Col. Sara Dudley is a U.S. Army finance and comptroller officer serving as the director of operations and support in the Army Budget Office, Pentagon. Her prior assignments within special operations involved direct work on countering terror finance. She holds a BS from the United States Military Academy, an MBA from Harvard University, and an MA from Case Western Law School in financial integrity.

Lt. Col. Steve Ferenzi is a U.S. Army strategist and Special Forces officer serving in the U.S. Special Operations Command Central J-5. He contributed to the development of the Irregular Warfare Annex to the 2018 National Defense Strategy and holds a Master of International Affairs from Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs.

Maj. Travis Clemens is a U.S. Army civil affairs officer in the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command with multiple deployments to Africa and the Middle East. He is the author of JSOU Report 20-4, Special Operations Forces Civil Affairs in Great Power Competition.

WE RECOMMEND

In “The Evolution of Economic Compliance,” Christopher Sims, PhD, describes how the economic aspect of national power has long been used to protect national interests, influence the behavior of other actors, and achieve objectives in the international arena. To read this article from the July-August 2021 Military Review, visit https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Journals/Military-Review/English-Edition-Archives/July-August-2021/Sims-Economic-Compellence/.

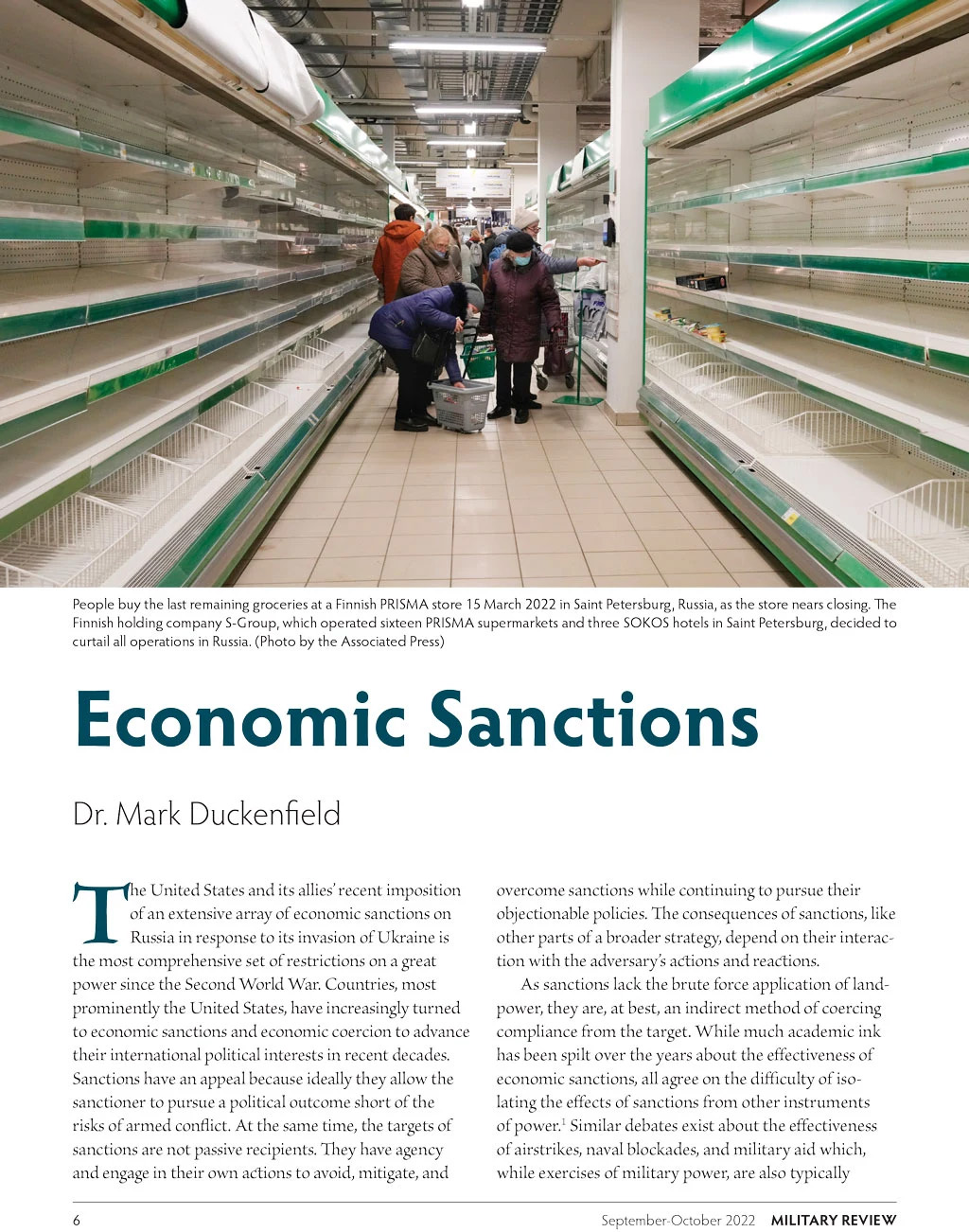

In “Economic Sanctions,” Dr. Mark Duckenfield describes how economic sanctions are one method of coercion that states use to pursue their international political objectives, whether to deter an action, compel a change in behavior, or punish another state. To read this article from the September-October 2022 Military Review, visit https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Journals/Military-Review/English-Edition-Archives/September-October-2022/Duckenfield/.

Back to Top