Disruption Is the Key to Delivering the Army of 20XX

Lt. Gen. Milford H. Beagle Jr., U.S. Army

Download the PDF

The chief of staff of the Army has deemed continuous transformation as one of his four focus areas. To understand what and how to contribute to continuous transformation, leaders at multiple levels require a common understanding of the fundamental elements necessary to transform and drive perpetual change. Bestselling author Charlene Li explains that transforming organizations do so through a path designed for the “future customer,” which requires “leadership that creates a movement to drive and sustain transformation … and a culture that thrives on disruptive change.”1

Disruptive transformation “isn’t only about innovation or technology.”2 It is largely a mindset and behavior change among leadership teams. In other words, it sets up organizations to thrive in a disruptive world. We must view the future battlefield as a disruptive world, and in doing so, leaders at multiple levels will be wise to heed a comment made by N. R. Narayana Murthy, cofounder of Infosys: “Growth is painful. Change is painful. But, nothing is as painful as staying stuck where you do not belong.”3 The changing nature of war and the creative use of technology makes future battlefields transparent, extended, and even more complex. It is the mindset of embracing change, new ideas, and the associated behaviors such as creativity, cooperation, and collaboration that will enable continuous transformation.

By 2030, the Army will field a new force capable of winning on the future battlefield against a variety of threats. Despite resource constraints that include time, money, and people with competing global force demands, rapid transformation is a tall task but not out of reach. To transform, we must disrupt the status quo. Creativity, cooperation, and collaboration at multiple levels in our Army are the fundamental elements needed to produce formations at echelon capable of winning our next battles and engagements.

Creativity

Creativity enables the ability to expand problems to an extent that new or alternative solutions tend to jump out. Disruptive transformation relies on thinking bigger not smaller, accurately capturing risk, and seeing as deeply into the future as possible. The role of creativity in disruptive transformation will allow us to shed biases and apprehension while illuminating possibilities. Our efforts to experiment must be focused on what doesn’t work versus what will work. In the latter, we run the risk of baking in a conclusion of a solution working. Experience is what you gain when you fail; therefore, if all things are geared to succeed, we run the risk of failing to learn and learn quickly.

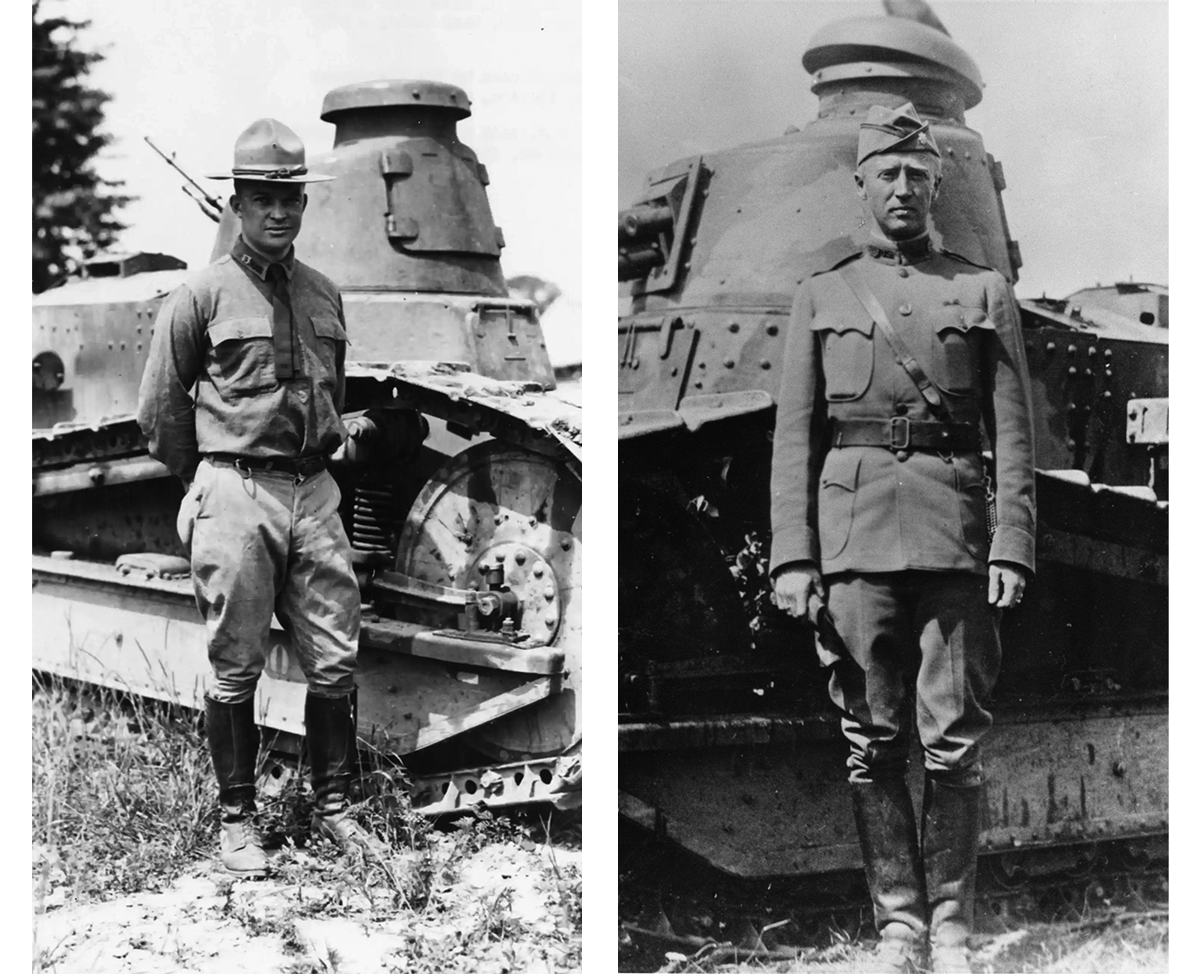

Left: Future general and president Dwight D. Eisenhower served at Camp Meade, Maryland, following World War I. Right: As a temporary lieutenant colonel, George S. Patton Jr., of the 1st Tank Battalion, stands in front of a French Renault tank in summer 1918. (Photos courtesy of the National Archives)

Prominent Disrupters

Following World War I, Maj. George S. Patton and Capt. Dwight “Ike” Eisenhower shared a passionate vision regarding the evolution of tank warfare, publishing articles in professional military journals extolling the importance of tanks to the future of the Army. The articles were disruptive to given wisdom of the time with respect to the “proper” role of tanks as they related to infantry. In the case of Eisenhower, he was threatened with court martial if he published further on the subject for advocating “dangerous” ideas. Notwithstanding, in time, Patton’s and Eisenhower’s ideas significantly influenced the direction of the Army’s operational and tactical employment of armor.

To read the article “Comments on ‘Cavalry Tanks’” by Maj. George S. Patton Jr., see the November-December 2015 edition of Military Review at https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Portals/7/military-review/Archives/English/MilitaryReview_20151231_art009.pdf.

To read Eisenhower’s article, “A Tank Discussion,” from the November 1920 edition of the Infantry Journal, visit https://cgsc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p4013coll7/id/799/. For more detail on the contributions of Eisenhower as an early advocate of developing tank warfare, see “The Making of a General: Ike, the Tank, and the Interwar Years” by Lt. Col. (Ret.) Thomas Morgan at https://armyhistory.org/the-making-of-a-general-ike-the-tank-and-the-interwar-years/.

Necessity accelerated creativity over the past several decades of war, but while in an interwar window, the urgency to be creative must be accelerated. Using robots to identify and disarm improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and synthetic aperture radars to find IEDs are both examples of necessity driving creativity due to the high level of casualties and injury caused by IEDs in Iraq and Afghanistan. Unmanned aircraft systems (UAS), once exclusively used for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance, are now being considered for casualty evacuation—a good example of creative urgency based on the technology available and the host of uses for UASs under multiple conditions of war.

Creativity means full commitment to change, and as insurance, avoid the temptation to turn back by burning the boats. Creative thinking also brings into focus the term “burning the boats.” This is a reference to Alexander the Great’s conquering the Persian Empire. In 334 BCE, after sailing a large fleet across the Hellespont Strait into Persian territory, Alexander ordered the ships to be burned. To his men’s dismay, he stated that we will either die here or return on Persian ships.4

The adage ‘better to have and not need than to need and not have’ counters everything about creativity and disruptive transformation. Creativity allows freer and bigger thinking even when resources are constrained.

Creativity will require us to burn some boats. The temptation can’t be to hold onto what we had because of the uncertainty of the next solution. In this sense, the adage “better to have and not need than to need and not have” counters everything about creativity and disruptive transformation. Creativity allows freer and bigger thinking even when resources are constrained. The simple ability to solve new problems in new ways and in some cases with old things affords a level of creative freedom across our force. The anchor of holding onto the old while trying to create the new simply won’t work. Conversely, if we find ourselves in need but don’t have, a lack of creativity can be the first place we may want to look.

Cooperation

Delivering the Army of 20XX will require a higher degree of cooperation inside and outside of our enterprise than ever to make our operational concepts come to fruition. Dominic Barton, head of McKinsey, once asserted that “we love to tell other people to change, but it’s not fun when you’re the one changing.”5 In this sense, we must act together in an effort to achieve a common purpose, which is the essence of cooperation. For disruptive transformation to occur, cooperation is not the byproduct of developing big ideas in a vacuum; the desired outcome is the sharing of the big ideas with others to find solutions. Linked to the previous behavior, cooperation brings about even more creativity.

Within the Training and Doctrine Command, there are many shining examples of robust cooperation occurring at the center of excellence (COE) level. As one example, the Cyber COE in conjunction with the community of experts across network requirements determined that system requirements designed in isolation fail to account for aggregate compute, store, and transport requirements. As another example, multiple COEs cooperated with the Aviation COE to determine that having specialty UASs for each branch or function is not feasible, but common airframes capable of carrying a variety of payloads is a better way forward.

Disruption isn’t always about new stuff; in some cases, it is as simple as cooperating to see if old things or concepts can be used in different ways. The ability to cooperate with a clear-eyed view of a common purpose will also lead to solution generation with things we already have. Showcased are the examples of extreme change and continual transformation by big organizations like Google and Facebook. But not all their change was revolutionary or evolutionary; some was disruptive. Many products used by these two business powerhouses “were third generation iterations of technology that already existed.”6 They were simply used in different ways. Cooperation means operating outside of the vacuum to continually drive change.

Collaboration

Finally, the third variable to disruptive transformation is collaboration. Collaboration in this sense goes beyond simply working together or as an extension of cooperation. Collaboration drives disruptive transformation by creating breakthroughs. As described by Li, these breakthroughs “are born from an uncanny ability to see the future and direct all the resources of your organization to chase after it.”7

Our own historical Army examples of this are the “Big 5,” which have been used ad nauseum to illustrate how modernization and transformation paid huge dividends in the post-Vietnam era.8 The collaboration across multiple commands to include the newly formed Training and Doctrine Command and Forces Command, both born in 1973, made possible the alignment of resources, energy, and effort to bring new doctrine (AirLand Battle), equipment (the Big 5), and organizations to fruition. Little was it known that the force designed, and the envisioned employment would play out in places like Panama and Iraq to great effect versus the plains of Europe.

This may be the case again in an uncertain, disruptive, and complex global security environment that our Army will face and be required to contribute to as part of a joint and multinational force. Therefore, collaboration to see as deeply into the future as possible and to direct scarce resources to the fundamental requirements necessary to contribute under multiple conditions of war (conventional, irregular, hybrid, etc.) will be how history will measure our success.

Conclusion

For continual transformation to achieve the outcomes we desire, we must foster a culture that thrives on disruptive change.

In terms of change, it is far easier to see what needs to be done versus how it will get done. The adage of there being more work in a “how” question than a “why” or “what” question certainly rings true in this case. Creativity, cooperation, and collaboration provide the how to develop and sustain disruptive transformation to push against the status quo where necessary, bureaucracy where needed, and complacency where found. To gain the speed we need in the short amount of time available, minimal disruption to the status quo won’t exactly be a winning recipe.

Disruptive transformation is more of a cultural mindset than innovation or technology; it is our “how to” for continual transformation. Li posits, “Innovation is the snooze button of corporate strategy, pushing tough decisions into the future.”9 Creativity will enable seeing the challenges of the future in breadth and depth in some ways clouded by quick win innovations. Cooperation allows us to break stovepipes to gain a better perspective of what is in the best interest of the Army’s contribution to a joint fight, regardless of theater and agnostic to conditions of war. Collaboration puts us in a position to break through the complexity of challenges that we will face in the future versus succumbing to creating solutions that are parochial, biased, or warfighting function centric. As Gen. Donn Starry once described, collaboration will enable us to operate from a “common cultural bias” to solve complex problems.10

When the security environment is as complex as what we will face in the future, we must tackle tough decisions head on by developing creative solutions. Future leaders of the Army of 20xx (what we describe as 2030, 2040, or 2050), or “the future customer,” will judge us not on a new piece of kit but rather how we got it there. When you comb through the archives of our post-Vietnam era history, the technology is the least impressive thing that you will find. The most impressive thing you will find is how leaders got there through the persistence of collaboration, healthy cooperation, and a sense of urgency-driven creativity.

Disrupting the status quo doesn’t mean flipping the apple cart, nor does it introduce a new term to use as the next big buzzword. In a simple way and in simple terms, it will help generate the speed, agility, and versatility needed to keep pace with change and complexity.

Notes

- Charlene Li, The Disruption Mindset: Why Some Organizations Transform While Others Fail (Oakton, VA: IdeaPress Publishing, 2019), 5–7.

- Ibid., 5.

- Ibid., 1.

- Ibid., 57–58.

- Ibid., 127.

- Ibid., 17.

- Ibid.

- “The U.S. Army Needs a ‘Small Five’ Modernization Strategy,” Lexington Institute, 16 October 2015, https://www.lexingtoninstitute.org/the-u-s-army-needs-a-small-five-modernization-strategy/.

- Li, The Disruption Mindset, 5.

- Donn A. Starry, “To Change an Army,” Military Review 63, no. 3 (March 1983): 20–27.

Lt. Gen. Milford Beagle Jr., U.S. Army, is the commanding general of the U.S. Army Combined Arms Center on Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, where he is responsible for integrating the modernization of the fielded Army across doctrine, organization, training, materiel, leadership, personnel, facilities, and policy. He has served in multiple leadership capacities from platoon through division levels, and his career deployments span the globe from Hawaii to the Republic of Korea. He previously served as the commanding general of 10th Mountain Division (Light). He holds a BS from South Carolina State University, an MS from Kansas State University, an MS from the School of Advanced Military Studies, and an MS from the Army War College.

Back to Top