History While It’s Hot

How a Group of U.S. Army Combat Historians Helped Preserve the GI’s Perspective in Europe during World War II

Carson Teuscher

Download the PDF

“How did the experiences of these interviews, and of being a ground-level historian, affect your understanding of the war?” she asked.

““I think I never really felt, as a combat historian, that I was making all that much contribution to the history of the war,” [Pogue] recollected. “I could see so little of it. All I was adding was a postscript, or something. But as a historian I was learning a great deal that might go into anything I wrote in the future.”

—Forrest C. Pogue and Holly C. Schulman, “Forrest C. Pogue and the Birth of Public History in the Army”

By 8 a.m. on 7 June 1944, the mist and smoke cleared sufficiently for Forrest C. Pogue to see Omaha Beach from the deck of his American troopship. He was one day late; the previous morning, Allied soldiers stormed Normandy’s beaches under withering enemy fire in one of the war’s defining moments. American soldiers aboard Pogue’s vessel jostled to see the action unfolding ashore. Pogue, awake since 4 a.m., remembered filling his vomit bag twice as the ship listed in the waves. Listening to the captain’s morning farewell, Pogue watched disembarking soldiers climb down nets into awaiting landing craft. He later recalled their cool, calm demeanor. Exhibiting “no special qualms, no bravado,” everyone knew their baptism by fire would come as soon as they entered the hills overlooking the beachhead.1

Rather than assault the beaches with amphibious troops, Pogue and several others remained onboard as spectators, witnessing the chaos beyond the beachhead. As a U.S. Army combat historian, Pogue’s war officially started that evening when medical personnel brought the dead and wounded soldiers back to the ship. Using a small notepad to record responses to his questions, Pogue tried to get at the true story of D-Day.2

He started by asking two wounded soldiers what happened onshore. One man grumbled about catching “hell from the snipers”; another cursed his luck for landing on the wrong beach. He had been shot through the hand climbing a tree to get a better view of the battlefield.3 Pogue scribbled a few lines in his notebook and continued interviewing men as they came aboard.

Pogue went ashore the next day. From 8 June 1944 until V-E Day, he roamed the front lines, shared foxholes with soldiers, interviewed men and officers, and recorded war from their perspective. Pogue’s work—and the work of many combat historians like him scattered throughout every major theater of operations—marked a radical development in American military affairs. Never had the U.S. Army employed combat historians to record firsthand experiences of frontline combat infantry units.

Of this process, Pogue recalled, “I don’t think it ever occurred to any of the people that I was working with … [that] we were making use of a new kind of history.”4 With its corpus of primary source material, after the war the military commissioned a groundbreaking series of “narrative operational accounts,” “theater and campaign histories,” “administrative histories,” and a “general popular history” of the Army’s involvement in the global struggle.5 Kent Roberts Greenfield, chief historian of the Army after the war, labeled the Army’s official historical venture “the most ambitious enterprise in the writing of contemporary history … undertaken in our time,” a true “pioneering effort to write narrative official military history.”6

The Army’s postwar enterprise to produce its own history certainly marked a radical departure from older forms of official Army history. Since the Civil War, the majority of Army historians had primarily engaged in preserving, collating, and publishing compendiums of official military documents. Military officers who strayed into the realm of narrative historical writing were often criticized for perpetuating institutional biases, glorifying violence, and ignoring the human cost of war.7

Between 1890 and 1914, civilian academics in the newly professionalized field of military history increasingly felt the glut of “narrowly specialized military histories” overshadowed the lived experiences of soldiers on the battlefield.8 Clamoring for unrestricted access to the Army’s military documents, as early as 1912 the American Historical Association and the U.S. War Department tried developing a “progressive coordinated history program” to “kindle a vital spirit of professionalism among its officers and elevate the study of war to an intellectual level consistent with other learned professions in American society.”9 However, underfunded, understaffed, and lacking popular appeal, this attempt at civil-military historical cooperation soon collapsed.

Still, though the endeavor faltered, it did not fail. During World War II, the Army responded emphatically to President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1942 executive injunction for all civilian and military departments to preserve “an accurate and objective account” of the war for future generations.10 By the end of the war, the Army’s combat historians—many of them civilian academics before the conflict—had roamed battlefields in every theater, collecting 17,120 tons of records, a capacious trove that would theoretically fill 188 miles of filing cabinets stacked end to end.11 After the war, many of these combat historians embarked on the decades-long production of the U.S. Army in World War II series, a seventy-eight-volume narrative account of America’s involvement in World War II known better as the “Green Books.”

This article briefly traces the recruitment, training, and fieldwork conducted by historians like Pogue who, plying their trade in the European theater of operations during World War II, helped lay the groundwork for “the largest undertaking in narrative historical work the American nation had ever known.”12 Col. William Ganoe, head of the Historical Section, G-3, European theater of operations, reiterated this point during the war: “It is difficult for us to realise that this Headquarters is now making vital history every day,” he wrote. “With conscious endeavour not to over-emphasize the importance of the Section charged with recording that history, it is nevertheless clear that the conception of researching and drafting the story of the ETO contemporaneously with passing events is probably one of the most signal advances in the writing of American history.”13

Collectively, U.S. Army historians like Pogue redefined official history by emphasizing historical objectivity while including ground-level testimonies to preserve the human side of war. Their corpus of wartime combat interviews and the novel methodological techniques they employed to curate and analyze them underpinned the Army’s decades-long postwar effort to preserve its history, largely overcoming the inaccessibility and institutional biases plaguing prewar official military histories.

Stumbling into the Job: The Recruitment of U.S. Army Combat Historians

Roosevelt’s March 1942 initiative kick-started an unprecedented expansion of military history programs within the U.S. Army. By June 1942, several War Department branches had already called up individuals to serve as historical officers within the organization’s various agencies. The commanding generals of the Army ground forces, Army air forces, and services of supply followed suit, calling historical officers to serve at each of their branch headquarters. During this early period, few knew what form of history the federal government wanted written, or what sort of activities these officers would undertake. Despite the order to preserve an objective narrative account of each agency’s wartime development, the lack of precedent, unclear staff assignments, and dearth of qualified staff nearly felled the operation before it began.14

In this climate, it was a miracle certain individuals ended up in the U.S. Army Historical Section at all. In spring 1943, a young private named Kenneth Hechler, training to become a tank commander at Fort Knox, Kentucky, was called out of the ranks by Brig. Gen. Stephen G. Henry. The commanding officer led Hechler to a room and began discussing a mandatory autobiography of “interests and experiences” he had written and submitted prior to his arrival on the base. Having been given a demerit for being caught one night poring over his assignment with a flashlight under his covers, the young private worried further trouble was afoot. Recalling the conversation after the war, he recalled how his superior officer surprised him, calling his “a most remarkable autobiography. I don’t think you ought to be a tank commander,” he said. “I think we ought to assign you to something a little bit more useful in the Army.”15

Hechler saluted him gratefully. Before enlisting in the Army as a private, he had received his PhD from Columbia University, working closely with renowned historians like Allan Nevins whose own interwar pioneering work has been assessed as the genesis of the modern academic oral history movement. As a graduate student before the war, Hechler acquired a substantial amount of experience. He taught courses, worked in the federal government’s Bureau of Budget, and even worked as a research assistant to Roosevelt’s speechwriter, Judge Sam Rosenman. Clearly, Hechler was more than qualified for work in the Army’s inchoate Historical Section.16

Like Hechler, a host of other individuals were found scattered throughout the Army with suitable backgrounds. Pogue—Gen. George C. Marshall’s future award-winning biographer who received the Bronze Star and French Croix de Guerre for frontline interviewing—was plucked from relative obscurity as an infantry private after a student he had taught before the war at Murray State working in an Army office recognized and recommended him for service.17 S. L. A. Marshall, a World War I veteran and “old-line newspaperman” for the Detroit News, was initially recruited when the prose and style of his 1942 report on the Tokyo Raid impressed members of the Army Historical Branch. Marshall later pioneered frontline interviewing techniques employed by historical officers in every theater.18

Some men simply recruited themselves. Maj. Jesse S. Douglas, a military historian serving on the records management branch of the Adjutant General’s Office, requested his own transfer when an August 1943 directive broadening the scope of the Historical Section arrived at his desk. Like Douglas, Israel Wice, later described as a “pearl of great price” in the Historical Section, requested his own transfer when he saw the same directive.19 An “old-boy network” functioning behind the scenes often used previous academic connections to pick out peacetime scholars from the mobilized ranks. Others, like Roland Ruppenthal, who applied for the Historical Section, heard nothing for several months, only to be admitted almost a year later. He never found out if he was selected from his own existing connections or churned through the cogs of military bureaucracy.20

These men, along with most who ended up in the Historical Section, “brought academic professional standards of scholarship with them.”21 Occupying positions of leadership were men who had taught history and literature at Harvard, Williams College, Johns Hopkins University, West Point, and Columbia—to name a few.22 Working for them were men ranging from Ivy League PhDs to African American English professor and army officer Ulysses Grant Lee Jr. who later wrote the definitive history of African American wartime military contributions.23

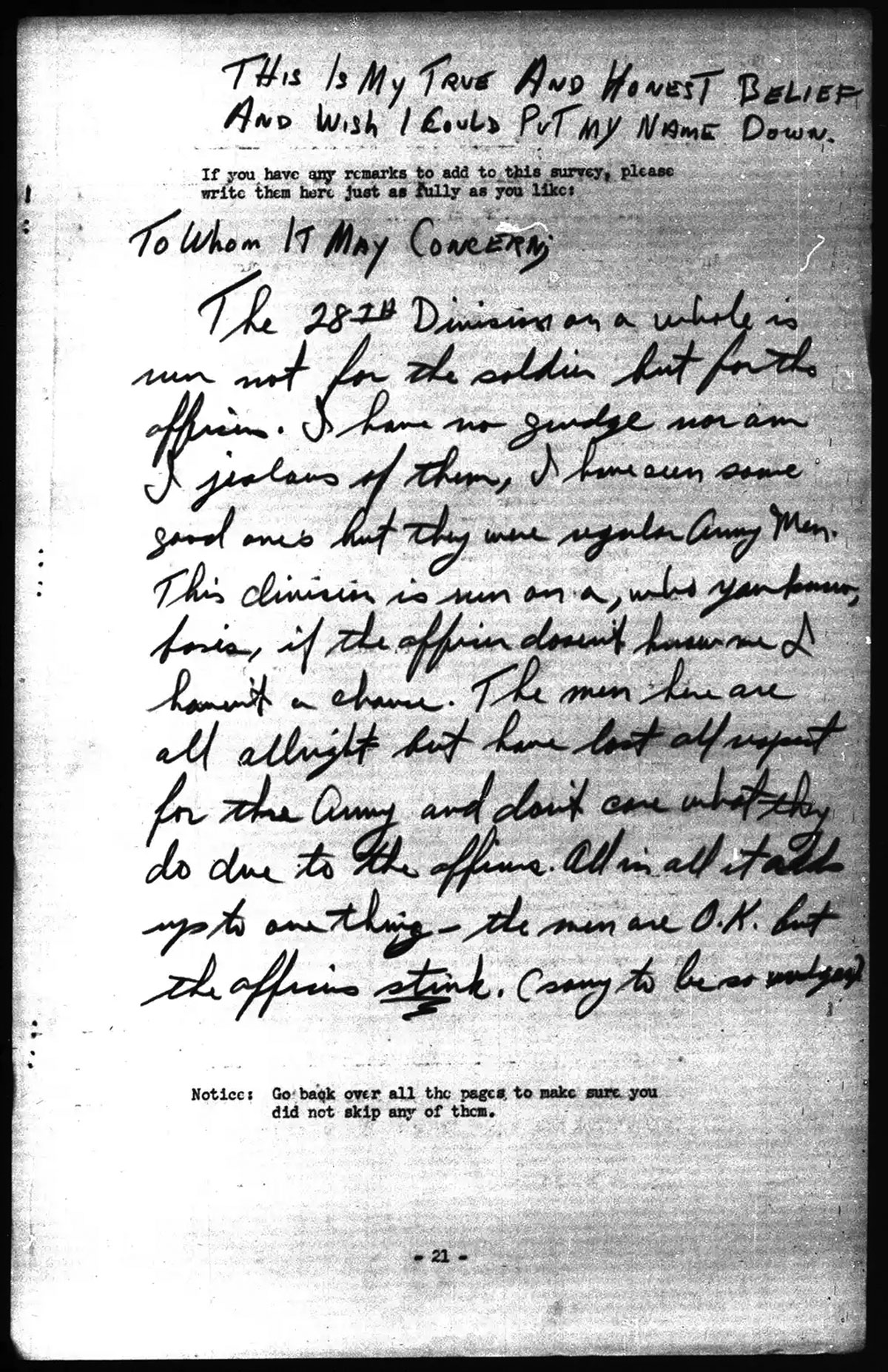

In one example of survey comment, an anonymous U.S. Army soldier opined a “true and honest belief” that “the 28th Division on a whole is run not for the soldier but for the officers.” The writer concludes, “All in all it adds up to one thing: the men are O.K. but the officers stink.”

Farsighted Army: World War II Social and Historical Research

Early in World War II, the U.S. War Department created the Army Research Branch, a social and behavioral sciences unit that surveyed and interviewed approximately half a million soldiers over the course of the war. Participating service members were promised anonymity.

Tens of thousands of those soldiers filled out the lengthy surveys and provided handwritten commentary.

While the quantitative data was digitized and made available through the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration and Cornell University’s Roper Center for Public Opinion Research, until 2018, the comments were available only to those who could view them on microfilm rolls on-site at the National Archives building in College Park, Maryland. Working closely with Virginia Technical University, The National Endowment for the Humanities provided grants to create searchable digital archives of the soldiers’ personal insights into their military service. More detail is available at https://liberalarts.vt.edu/news/articles/2018/04/insights-of-american-soldiers-during-world-war-ii-to-be-made-ava.html.

Their academic backgrounds reinforced a commitment to rigorous objectivity, a professional standard the fledgling Historical Section embraced. As Pogue later commented, “The field commanders stood by us when we took the point of view that we did not write history for the purpose of selling the Army as an all-perfect organization.”24 They were determined to keep official history honest. The recruitment process provided a critical injection of “energy, fresh approaches … innovation, and determination” into a historical branch suffering in the beginning from vague objectives and bureaucratic infighting.25 Finding their way through various channels to their respective positions, their recruitment began, in official historian Stetson Conn’s words, the “honest cooperation between two professional groups, the professional officers of the Army and the professional historians of the nation, each recognizing and respecting the needs and interests of the Army.”26

Training for the Field

Even in the months before the advent of the Historical Section, many combat historians gleaned a great deal of knowledge about the Army’s organization from basic training and boot camp. During his first year of training as a private, Pogue frequently went to the camp library to digest books about the mechanics of military operations, helping him better understand those he later interviewed.27 Likewise, despite his Ivy League pedigree, Hechler enlisted as a private to, in his words, “learn a little bit about the army from the bottom up.”28 As their training became more formalized, their background knowledge of military structures, processes, and responsibilities lent insight into the quotidian existence of their historical subjects.

Building on Marshall’s pioneering use of the combat interview in the Pacific, several of the newly formed teams of combat historians initially met in Washington to receive a more academically rigorous training under Col. Hugh M. Cole.29 There, combat historians spent several weeks receiving an indoctrination in military history and were briefed on the nature of after action reports and official records.30 Using documents sourced from the Papuan campaign in the Pacific, one group reconstructed a narrative history of the battle for New Guinea. Teaching them to identify the types of documents required to compose a balanced history, the practice exposed them to another reality: Pogue soon observed that while “modern war was better documented than conflicts of the past, the task of piecing together the truth was just as difficult.”31 It was “locating and remedying those voids in the historical evidence,” according to Edward Drea, that “became an integral part of the expanding demands of their work.”32

Serving as an editorial analyst in the field during World War II, African American scholar Capt. Ulysses Lee, PhD, later wrote The Employment of Negro Troops while serving as a member of the Office of the Chief of Military History from 1946 to 1952. Drawing upon both exhaustive research as well as his personal interactions with African American soldiers during the war, this volume provides both a candid history as well as biting social analysis and commentary pertaining to the social factors necessary for minority soldiers to serve optimally in the U.S. Armed Forces. It has long be regarded as the definitive U.S. Army standard work on the subject. To view this publication, visit https://history.army.mil/html/books/011/11-4/CMH_Pub_11-4-1.pdf.

The TRADOC historical monograph SLAM—The Influence of S.L.A. Marshall on the United States Army provides a brief biographical overview of the individual generally regarded as the originator of modern-day Army combat research methodology. This volume touches upon the many facets of the career of Marshall and his contributions to each as a World War I soldier, a newspaper reporter, a war correspondent, a combat historian, and ultimately, a war critic. Marshall’s pioneering methodology for collecting interviews directly from combat soldiers who had just participated in battles is generally regarded among current military historians as the foundation for one of the most important dimensions of today’s U.S. Army standard historical collection operating procedures.

To view this monograph, visit https://history.army.mil/html/books/070/70-64/cmhPub_70-64.pdf.

Combat historians were soon flown to their theaters of operation to undergo additional training. In-field training was less rigorous. Stationed in England on the eve of D-Day, Pogue and his fellow historians spent hours each day studying Army tactics and organization. They were, however, also free to roam and explore. On any given walk, Pogue recalled, “one could meet people from every sort of background.”33 Their informal walks gave them the opportunity to hear personal wartime experiences from a variety of individuals by starting open, honest conversations—a practice that soon became become a hallmark of their wartime service.

While abroad, Pogue and his fellow historians in the European theater of operations thirsted for “access to ‘the big picture.’”34 Only after the implementation of Allied deception plans, the conferral of security clearances, and proximity to the cross-channel invasion were the Army’s field historians granted the ability to work with classified documents. Soon, their newfound appreciation for the magnitude of Allied D-Day plans ushered them into the final phase of their preparation for fieldwork: the feverish digestion of operational planning materials. “Much time has been spent in reading through plans and annexes for the coming operation. Time is terribly short,” one historian noted. “The entire team should have been with the Army headquarters months ago.”35

Prior to D-Day, Pogue’s section of combat historians were assigned equipment, slept outside among the soldiers, and for the first time began experiencing “the real feel of war.”36 Their formal and informal preparation cultivated the strategic awareness and interpersonal skills needed to interview others, contextualize battlefield developments, operate within a command hierarchy, adapt to the chaos of operational developments, and synthesize fragmented battlefield data into manageable, streamlined accounts. Operating under strict time constraints, the preparation process was overwhelming, but paled in comparison to the task ahead. “We asked each other,” Pogue recalled, “if we can’t even read the [D-Day] plan in a month, how can we expect in length to get a story of what happened?”37

Preserving History “While It’s Hot”

In the fall of 1944, combat historians in the European theater lived in the field—exposed to the elements alongside the men whose stories they sought to preserve. German snipers on the Allied perimeter for months had been targeting officers whose bars on their helmets would “glisten in the sun.” Hechler, following the lead of those around him, covered his own bars with cosmoline, a “sticky, greasy” waterproof material. One day, a jeep bedecked with American flags careened into the camp where he was stationed. Hechler recalled being summoned by the jeep’s primary occupant—Gen. George S. Patton—who roared, “God damn it, are you proud of your rank?” Replying in the affirmative, Patton rebuffed Hechler: “Well, then dig that goddamn stuff off your helmet or I’ll rip that insignia off of your uniform right here and now!”38 For combat historians as any other soldier, anything could happen in the field.

Fieldwork required adaptability; each campaign was an ever-unfolding learning experience. Sometimes combat historians slept in the open through rainstorms and random artillery bursts. Those coming ashore after D-Day dug their own foxholes. Frequently within hearing distance of the front, occasionally, as the battle lines shifted, they even took enemy fire. “I had the happy opportunity of being sniped at once,” Maj. Jerry O’Sullivan, a member of Pogue’s team in France, recorded two weeks after D-Day. “It is pretty noisy and rugged [near the front], but I must confess I’d have liked nothing better than to have stayed on.”39 Lt. John S. Howe labeled frontline operations “a welter of confusion and mystery.”40 They rarely had special amenities: It was D+29, or 5 July 1944, when Pogue finally noted his first change of clothes into his diary; he had not changed trousers since leaving London for his unit on 28 April, nor cleaned them since leaving Memphis in March.41

Like their combat environment, interactions with peers often proved unpredictable. Some interviews unfolded spontaneously over the course of a few minutes. Consulting maps, written records, and multiple eyewitnesses, other sessions lasted several hours. While most interviews were cordial, reactions from certain uncooperative commanders ranged from belligerently blowing off historians they viewed as interlopers to gently encouraging them to act “contrary to their original instructions.”42 Aware their reputations were on the line, commanders and soldiers were often reluctant to open up about their combat experience, forcing historians to reconcile misaligned memories and mediate arguments between irritated divisional chiefs of staff and other personnel over their interpretation of specific events. Drea wrote how historians’ personalities proved crucial in guiding their historical efforts as “resourcefulness, imagination, and talent” were often required to convince superior officers they were worth the time.43 Where these skills failed, cigarettes and flattery went a long way.

Operating within a friction-filled battlespace, combat historians spent their days moving and interviewing, compiling notes to supplement after action reports, and later, drafts of their campaign narratives. They carried portable typewriters with them, writing on desks in tents, trailers, or the great outdoors. With one pair of historians assigned to each of the Army’s combat corps, the duos acquired strategic plans, maps, and overlays to contextualize the unit engagements unfolding before them—“down to the division, regiment, battalion, company, and platoon levels.”44 According to Hechler, historians added individual testimonies to their narrative analyses to make the after action reports more “meaningful,” all in an attempt “to catch these things while they were still hot in the minds of the people.”45

Writing after the war, Chief Historian of the Army Kent Greenfield argued that “oral history and interviewing techniques” tended to “yield diminishing returns as time passes.”46 Because memory becomes more selective and fragile over time, “obtaining on the ground and at the time those happenings and statements which have a chance of being lost or distorted later” ultimately became one of the foremost contributions of the Army’s combat historians.47 Observations litter the Historical Section’s wartime records citing the importance of conducting their work in a timely manner. As one example, as Maj. Jerry O’Sullivan walked the Normandy beachhead on D+11, he recognized “a crying need for a draftsman” to sketch the unfolding scenes “because this beach changes from day to day, hour to hour.” “My idea in getting this thing on paper,” he told his superior, “is that if it isn’t done soon, the whole thing will be lost.”48 Such observations reflect the degree to which combat historians hoped to preserve firsthand memories of events while they were yet unfolding.

Conclusion

Today, as the last members of the war generation pass away, personal access to firsthand memories of World War II are in increasingly short supply. Thanks to the enduring corpus of published work created by the historians of the Army’s Historical Section in the conflict’s aftermath, members of the public today can freely learn about every aspect of the United States’ civil-military involvement in the war.

The legacy of the Army’s combat historians, however, reverberates beyond the “Green Books” and their fingerprint on future official histories. Such work possessed obvious utility as a guide to future leaders, “so that, when we are again involved in war, this country may be prepared to repeat that which proved to be successful, and avoid that which has caused us trouble.”49 In their professional lives, individuals like Pogue and Hechler, among others, pursued illustrious academic and public service careers after the war; to this day, the Organization of American Historians continues to confer an annual “Forrest C. Pogue” award due to his wartime use of oral history in combat and subsequent efforts to champion its utility within the academy. Modeling contemporary historical endeavors on their original work, the Army’s Military History Detachment today still employs combat historians in battlefield operations—many of them civilian academics—and has in every major conflict since World War II.

Arguably, however, their biggest contribution remains housed in archives around the world. Merging academic standards of objectivity with their mandate to produce digestible narrative histories, thousands of firsthand interviews conducted during their time overseas form the backbone of a priceless repository of wartime memories preserved on microfilm designed to survive millennia. By preserving the human face of World War II, these combat historians facilitated the creation of official histories that never lost sight of the men and women who lived them, inspiring future generations to do the same.

Military Review expresses its great appreciation to the following individuals who conducted research and facilitated acquiring rare photo imagery in the development of this article: LaDonna Hamontree, Pogue Library, Murray State University, Kentucky; Kenny Kemp, visual editor/chief photographer, Charleston Gazette-Mail, West Virginia; Dan Barbuto and Cynthia Leighton, Ike Skelton Combined Arms Research Library, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas; and Gregory Statler, U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

Notes

- Epigraph. Forrest C. Pogue and Holly C. Schulman, “Forrest C. Pogue and the Birth of Public History in the Army,” The Public Historian 15, no. 1 (Winter 1993): 35, accessed 23 September 2021, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3378031.

- Forrest C. Pogue, Pogue’s War: Diaries of a WWII Combat Historian (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2001), 54–55.

- Ibid., 56.

- Ibid., 58.

- Pogue and Schulman, “Forrest C. Pogue and the Birth of Public History in the Army,” 31.

- Edward J. Drea, “Change Becomes Continuity: The Start of the U.S. Army Green Book Series,” in The Last Word? Essays on Official History in the United States and British Commonwealth, ed. Jeffrey Grey (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2003), 83–104; “Military History of the Second World War,” Memorandum No. W345-21-43, August 3, 1943, Historical Directives (National Archives Microfilm Publication 63-9, Roll 23), U.S. Army, U.S. Forces, European Theater, Historical Division: Records, 1941–1946, Record Group [RG] 498, National Archives and Records Administration II [NARA II], College Park, Maryland, 1.

- Kent Roberts Greenfield, The Historian and the Army (New York: Kennikat Press, 1953), 6.

- Carol Reardon, Soldiers and Scholars: The U.S. Army and the Uses of Military History, 1865-1920 (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1990), 165. Col. William Ganoe, Chief of the Historical Section, G-3, European theater of operations during World War II, observed how the Army’s new endeavor differed from past official military histories: “War data in America … has been particularly scant because we had to dig what was left from the termites years later. It too often was without life, truth or its main parts. What good does it do the student at Leavenworth or the War College to know that Hooker suddenly went into a defensive position at Chancelorsville or that the First Division crunched the tail of Dickman’s Corps. The illuminating, revealing and educationally helpful thing is why the commanders did what they did. That is the missing mortar. With bricks alone (after fragments), we can’t build worthwhile experience tables.” See Untitled, n.d., Administrative History Collection, Historical Section, ETOUSA, Folder 161, (National Archives Microfilm Publication 63-9, Roll 22), U.S. Army, U.S. Forces, European Theater, Historical Division: Records, 1941–1946, RG 498, NARA II.

- John Whiteclay Chambers II, Oxford Companion to American Military History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 224, 316.

- As an example, the promised documentary compendiums on America’s involvement in World War I would not be published until 1948. See Bell I. Wiley, Historical Program of the U.S. Army 1939 to Present [1945] (Washington, DC: Office of the Chief of Military History, U.S. Army, 1945), 1–3.

- Ibid., 8–9.

- Greenfield, The Historian and the Army, 6.

- Stetson Conn, “Launching ‘The United States Army in World War II,’” Army History, no. 31 (1994): 37, accessed 13 October 2021, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26304192.

- “Notes on Importance and Possible Extension of this Section,” May 27, 1943, Administrative History Collection, Historical Section, ETOUSA, Folder 161, (National Archives Microfilm Publication 63-9, Roll 22), U.S. Army, U.S. Forces, European Theater, Historical Division: Records, 1941–1946, RG 498, NARA II.

- Drea, “Change Becomes Continuity,” 85; Jamie W. Moore, “History, the Historian, and the Corps of Engineers,” The Public Historian 3, no. 1 (Winter 1981): 64, accessed 23 September 2021, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3377162; Wiley, Historical Program of the U.S. Army 1939 to Present [1945], 9–14.

- Ken Hechler, interview by Niel M. Johnson, “Oral History Interview with Ken Hechler,” Harry S. Truman Library and Museum, 29 November 1985, 57–60, accessed 23 September 2021, https://www.trumanlibrary.org/oralhist/hechler.htm.

- Ibid.

- Pogue and Schulman, “Forrest C. Pogue and the Birth of Public History in the Army,” 30.

- Chambers, Oxford Companion to American Military History, 420; F. D. G. Williams, SLAM: The Influence of S.L.A. Marshall on the United States Army, ed. Susan Canedy (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command, 1999), v, accessed 23 September 2021, https://history.army.mil/html/books/070/70-64/cmhPub_70-64.pdf.

- Wiley, Historical Program of the U.S. Army 1939 to Present [1945], 40, 43.

- Drea, “Change Becomes Continuity,” 87.

- Rebecca Conard, Benjamin Shambaugh and the Intellectual Foundations of Public History (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2001), 156.

- Stetson Conn, Historical Work in the United States Army 1862-1954 (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History), 190; “Military History of the Second World War,” 2.

- See Ulysses Lee, United States Army in World War II Special Studies: The Employment of Negro Troops (Washington, DC: Office of the Chief of Military History, U.S. Army, 1966).

- Conard, Benjamin Shambaugh, 156. For more on the professionalization of history in the United States and the discipline’s quest for objectivity, see Peter Novick, That Noble Dream: The ‘Objectivity Question’ and the American Historical Profession (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988).

- Drea, “Change Becomes Continuity,” 86.

- Conn, “Launching ‘The United States Army in World War II,’” 41.

- Pogue, Pogue’s War, 5.

- Johnson, “Oral History Interview with Ken Hechler,” 57–60.

- G. Kurt Piehler, “Veterans Tell Their Stories and Why Historians and Others Listened,” in The United States and the Second World War: New Perspectives on Diplomacy, War, and the Home Front, ed. G. Kurt Piehler and Sidney Pash (New York: Fordham University Press, 2010), 222.

- Pogue, Pogue’s War, 2.

- Ibid.

- Drea, “Change Becomes Continuity,” 88.

- Pogue, Pogue’s War, 8.

- Ibid.

- “Report of Activities, 7–15 May 1944,” Memorandum to Colonel William A. Ganoe, May 25, 1944, Historical Section, ETO (1943–1945), (National Archives Microfilm Publication 63-9, Roll 23), U.S. Army, U.S. Forces, European Theater, Historical Division: Records, 1941–1946, RG 498, NARA II, 1–3; Pogue, Pogue’s War, 27.

- Pogue, Pogue’s War, 23.

- Ibid., 30–31.

- Johnson, “Oral History Interview with Ken Hechler,” 70–71.

- Sgt. Major Jerry O’Sullivan to Colonel William A. Ganoe, Chief of the Historical Section, European theater of operations, June 17, 1944, Historical Team Reports (National Archives Microfilm Publication 63-9, Roll 23), U.S. Army, U.S. Forces, European Theater, Historical Division: Records, 1941–1946, RG 498, NARA II, 1–2; H. Lew Wallace, “Forrest C. Pogue: A Biographical Sketch,” The Filson Club Quarterly 60, no. 3 (July, 1986): 383–84.

- John S. Howe, “Report of Activities, 19–26 June 1944,” June 26, 1944, Historical Section HQ, First U.S. Army, (National Archives Microfilm Publication 63-9, Roll 23), RG 498, NARA II.

- Pogue, Pogue’s War, 140.

- Ibid., 9; “Diary—Team #I—HQ, ETOUSA,” May 15, 1944, Historical Section HQ, First U.S. Army, (National Archives Microfilm Publication 63-9, Roll 23), RG 498, NARA II, 13.

- Drea, “Change Becomes Continuity,” 88–89. O’Sullivan noted how Pogue found “Colonels and Generals eager to talk to him,” adding from his own experience “that if those men find you know what you want and are sincere about what you are doing they will go out of their way to cooperate.” O’Sullivan to Ganoe, 1.

- Johnson, “Oral History Interview with Ken Hechler,” 64–65.

- Ibid.

- Greenfield, The Historian and the Army, 10.

- “Record of Oral Material,” Memorandum to Brigadier General Julius C. Holmes, Deputy Assistant Chief of Staff, G-5, SHAEF, n.d., (National Archives Microfilm Publication 63-9, Roll 23), RG 498, NARA II.

- O’Sullivan to Ganoe, 2.

- “History of the Services of Supply, European Theater of Operations, United States Army,” June 23, 1943, Historical Directives, (National Archives Microfilm Publication 63-9, Roll 23), RG 498, NARA II, 1.

Carson Teuscher specializes in military history at Ohio State University. Teuscher received his BA in history from Brigham Young University in 2016 and an MSt in U.S. history from the University of Oxford in 2017.

Back to Top