Stability Operations in Syria

The Need for a Revolution in Civil-Military Affairs

Anthony H. Cordesman

Download the PDF

In an ideal world, the U.S. military would only have a military role. But, in practice, no one gets to fight the wars they want, and this is especially true today. The United States is deeply involved in wars that can only be won at the civil-military level, and where coming to grips with the deep internal divisions and tensions of the host country, and the pressures from outside states, are critical. Unless the United States adapts to this reality, it can easily lose the war at the civil level even when it wins at the military level. This is especially true in the case of the “failed states” where the United States is now fighting. The United States either has to hope for a near-miraculous improvement in the governance and capability of host-country partners, or focus on successful civil-military operations as being as important for success as combat.

So far, the United States has failed to recognize the sheer scale of the civil problems it faces in conducting military operations. It has failed to understand that it needs to carry out a revolution in civil-military affairs if it is to be successful in fighting failed-state wars that involve major counterinsurgency campaigns and reliance on host-country forces. The U.S. military role in Syria is a key case in point, and it illustrates all too clearly that any military effort to avoid dealing with the full consequences of the civil side of war can be a recipe for failure.

A Lack of Meaningful Directives and Doctrine

Part of the problem is that this is an area for which there is neither meaningful guidance nor doctrine. Department of Defense (DOD) Instruction Number 3000.05, Stability Operations, is so vague as to be meaningless.1 It defines stability operations as “an overarching term encompassing various military missions, tasks, and activities conducted outside the United States in coordination with other instruments of national power to maintain or reestablish a safe and secure environment, provide essential governmental services, emergency infrastructure reconstruction, and humanitarian relief.”2

The policy sections of Instruction 3000.05 call for virtually every activity imaginable without setting meaningful priorities or goals:

a. Stability operations are a core U.S. military mission that the Department of Defense shall be prepared to conduct with proficiency equivalent to combat operations. The Department of Defense shall be prepared to:

(1) Conduct stability operations activities throughout all phases of conflict and across the range of military operations, including in combat and non-combat environments. The magnitude of stability operations missions may range from small-scale, short-duration to large-scale, long-duration.

(2) Support stability operations activities led by other U.S. Government departments or agencies (hereafter referred to collectively as “U.S. Government agencies”), foreign governments and security forces, international governmental organizations, or when otherwise directed.

(3) Lead stability operations activities to establish civil security and civil control, restore essential services, repair and protect critical infrastructure, and deliver humanitarian assistance until such time as it is feasible to transition lead responsibility to other U.S. Government agencies, foreign governments and security forces, or international governmental organizations. In such circumstances, the Department will operate within U.S. Government and, as appropriate, international structures for managing civil-military operations, and will seek to enable the deployment and utilization of the appropriate civilian capabilities.

b. The Department shall have the capability and capacity to conduct stability operations activities to fulfill DOD Component responsibilities under national and international law. Capabilities shall be compatible, through interoperable and complementary solutions, to those of other U.S. Government agencies and foreign governments and security forces to ensure that, when directed, the Department can:

(1) Establish civil security and civil control.

(2) Restore or provide essential services.

(3) Repair critical infrastructure.

(4) Provide humanitarian assistance.

c. Integrated civilian and military efforts are essential to the conduct of successful stability operations. The Department shall:

(1) Support the stability operations planning efforts of other U.S. Government agencies.

(2) Collaborate with other U.S. Government agencies and with foreign governments and security forces, international governmental organizations, nongovernmental organizations, and private sector firms as appropriate to plan, prepare for, and conduct stability operations.

(3) Continue to support the development, implementation, and operations of civil-military teams and related efforts aimed at unity of effort in rebuilding basic infrastructure; developing local governance structures; fostering security, economic stability, and development; and building indigenous capacity for such tasks.

d. The Department shall assist other U.S. Government agencies, foreign governments and security forces, and international governmental organizations in planning and executing reconstruction and stabilization efforts, to include:

(1) Disarming, demobilizing, and reintegrating former belligerents into civil society.

(2) Rehabilitating former belligerents and units into legitimate security forces.

(3) Strengthening governance and the rule of law.

(4) Fostering economic stability and development.

e. The DoD Components shall explicitly address and integrate stability operations-related concepts and capabilities across doctrine, organization, training, materiel, leadership and education, personnel, facilities, and applicable exercises, strategies, and plans.3

… the grand strategic goal of warfighting is never just to produce a favorable military outcome or to defeat the enemy. It is to win as lasting a victory as possible in political, economic, and security terms.

The revised U.S. Army field manual on stability operations—Field Manual 3-07, Stability—provides much better general guidance, but it tacitly assumes that the host-country government is competent and willing to carry out all necessary reforms.4 It ignores the lessons of the Vietnam conflict, the campaigns in Afghanistan from 2001 to date, and the campaigns in Iraq from 2003 to the present. It ignores virtually all of the realities of dealing with real-world host-country governments, and what past and current conflicts have revealed about the problems in simply calling for a whole-of-government approach. As for the overlapping guidance in DOD Directive 2000.13, Civil Affairs, it is even more vague, general, and decoupled from the wars the United States is now fighting.5

While the United States did attempt something approaching nation building in Afghanistan between 2001 and 2014 and in Iraq between 2004 and 2011, few argue that these efforts produced effective civil-military coordination, and both largely failed. If anything, these failures have led the United States to try to both minimize the role of U.S. ground forces in failed-state wars and restrict stability operations to a minimum. The very term “nation building” is now one the United States seeks to avoid. In practice, stability operations are still being generally treated as only a passing phase in warfare. The key goal for military forces is to defeat the enemy, and dealing with civilians now occurs largely at the tactical level and consists largely of humanitarian relief.

This is a fundamentally unrealistic approach to modern U.S. military operations. It ignores the real-world nature of the wars in Vietnam, the Balkans, Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Yemen, and Syria—the case study that is the focus of this analysis. It also ignores just how often the U.S. military is forced to engage in stability and civil-military operations. As a Defense Science Board study, Transition To and From Hostilities, pointed out in 2004, “Since the end of the Cold War, the United States has conducted new stabilization and reconstruction operations every 18 to 24 months.”6 More importantly, the report revealed that the cost of these operations far outstrips the cost of major combat operations in both human resources and treasure.7

Like far too many cases in the past, it also ignores the fact that grand strategy can only succeed if the United States not only terminates a conflict successfully, but also creates conditions that provide lasting security and stability. All wars have an end, and the grand strategic goal of warfighting is never just to produce a favorable military outcome or to defeat the enemy. It is to win as lasting a victory as possible in political, economic, and security terms. The kind of thinking that led the Office of the Secretary of Defense to take a far more serious look at stability operations in its Biennial Assessment of Stability Operations Capabilities in 2012 is even more critical today, and cases like Syria illustrate the point.8

Conventional Wars Never Have a Conventional Ending

America’s military history provides a vital prelude to any case study of issues related to stability operations. Throughout American history, this aspect of war has presented major and lasting problems—even when wars were fought on territory in or nearby U.S. territory, even when they used tactics and strategy focused on conventional warfare, and even when the United States won decisive victories at the tactical and strategic levels.

The American colonies had no clear plan for peace when the United States won independence. Virtually every war with Native Americans ended in an unstable peace and unintended tragedy for Native Americans. The United States fought the Mexican-American War in an era of “manifest destiny,” but with no clear plan for its outcome, and Mexican Americans suffered for decades as a result. There was no plan for victory at the end of the Civil War, and the result was Reconstruction and nearly a century of racism.

The Spanish-American War was the first major U.S. military adventure distant from U.S. territory, but a victorious United States had no victory plan for Cuba. It subsequently annexed the Philippines almost by accident and then had to fight a counterinsurgency campaign against native Filipinos. And, in its next military conflict, the U.S. failure to create a stable end to World War I played a key role in causing World War II.

The United States ended World War II without any clear plan for its aftermath in either Europe or Japan. The initial U.S. efforts to enforce a rapidly improvised version of the Morgenthau Plan to limit the future role of Germany—and U.S. failure to focus on recovery and refugees—helped create a crisis that was only alleviated by the Marshall Plan and U.S. acceptance of the need to provide aid because of the advent of the Cold War.

The United States did improvise an effective occupation effort in Japan after World War II, but economic recovery and political stability came as much from the flood of U.S. spending triggered by the Korean War as from U.S. plans. Fortunately, the United States did provide aid to South Korea, but again because the war did not really end and aid was clearly critical.

Since that time, U.S. failures to develop a stable civil sector in Vietnam were ultimately as critical as the weaknesses in South Vietnamese forces. The United States first avoided dealing with the civil aftermath of the war with Iraq in 1991, then invaded without any civil and conflict termination plans in 2003. It indulged in nation building in Iraq from 2004 to 2011, and it now fights the Islamic State (IS) in both Iraq and Syria without any meaningful plan for what happen after IS’s defeat. The United States carried out similar operations in Afghanistan from 2001 to 2014. As reports by the Office of the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and World Bank make all too clear, most of the U.S. nation-building effort has been no more successful than in Iraq, and the United States again has no clear plans for the future.9

The Challenge of “Failed State” Wars

These lessons are particularly important now that the United States is committed to a series of wars, like that in Syria, which are anything but conventional. The United States is now fighting what are largely counterinsurgency campaigns, although they are sometimes labeled as fights against terrorism. It is fighting major campaigns—mixing airpower with train, advise, and assist units; Special Forces; and other small land-combat elements in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria. At the same time, the United States is playing a limited role in other conflicts in Libya, Yemen, Somalia, and parts of sub-Saharan Africa.

In all of these wars, the failures of the host country to meet their people’s needs in governance, development, and security—and their gross corruption and incompetence—is as much a threat as the enemy. They are all wars against an enemy with a hostile ideology—violent Islamic extremism—and the fight for hearts and mind is critical. They are all wars where outside powers like Iran and Turkey play a major role, where U.S. local and regional strategic partners are critical, and where combinations of rival ethnic, sectarian, and tribal groups compete for power, often to the point of near or actual civil war.

In practical terms, however, they are wars where the United States now lets the immediate tactical situation dominate, where there is no clear strategy for military victory, and where there is no grand strategy for full-conflict termination or for post-conflict stability and security. In these conflicts, the United States has largely turned away from any form of nation building. The limited U.S. military presence on the ground is not backed by major aid efforts or by a forward-deployed civilian presence, and the State Department and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) are no longer involved in civil-military operations. In one key case—Afghanistan—only a limited counterterrorism force plays a forward-combat role. In Iraq, the ground presence is deliberately limited and focused on tactical support. And in Syria, the United States relies on small detachments of Special Forces to support Syrian Kurdish and “moderate” Arab rebel forces, while other U.S. and allied forces train small elements in countries like Jordan and Iraq.

As a result, stability operations either do not exist or are narrowly focused on specific regions and small tactical areas of operation, and failed host governments are left to act on their own. There is no clear civil effort to bring lasting stability, and outside states like Iran, Russia, Turkey, and Pakistan play a more active civil-military role. If anything, the official U.S. posture toward the host governments in Afghanistan and Iraq is largely one of constantly claiming civil progress that is exaggerated or does not exist, or one of ignoring the full range of civil problems—effectively a strategy based on hope and denial.

Syria: The Worst Test Case?

It is an open question as to whether Syria is the worst test case in either strategic or humanitarian terms. In many ways, Syria is only of marginal strategic interest to the United States as long as it is not the center of some extremist “caliphate” and no longer exports terrorism. Afghanistan may only have limited strategic importance in absolute terms, but it has become a symbol of U.S. capability, and it too presents fewer host-country problems. Yemen has even less strategic importance than Syria unless it becomes a threat to maritime shipping or far more of a threat to Saudi Arabia and Oman. Even so, the situation in Yemen has deteriorated to the point where it rivals Syria as a humanitarian disaster.

Syria, however, cannot be decoupled from the war in Iraq. Iraq’s civil-military and host-country problems are not as severe as in the other wars the United States is now fighting, but Iraq is a major oil power that shares a border with Iran, and it has far more strategic importance to the United States. It is also hard to see how the United States can help Iraq achieve lasting stability unless Syria is stable. An unstable Syria also threatens allied and friendly states like Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey, and Syrian instability presents a serious risk that any defeat of IS elsewhere will simply lead to a new violent Islamist extremist movement in eastern Syria that could become a major threat to the interests of the United States and its allies.

More broadly, U.S. policy in Syria is widely seen as a failure and a sign of growing American weakness in the Middle East. U.S. diplomacy has so far failed to counter or balance Russian influence and has become a sideshow to other efforts to negotiate a ceasefire. While the United States plays a military role in the fight against IS in Syria, it conspicuously has failed to create effective, unified, and moderate Arab rebel forces.

The United States has avoided committing large ground forces to Syria and has avoided becoming involved in a serious air war with pro-Bashar al-Assad forces. However, this has come at the cost of far more decisive Russian, Iranian, and Hezbollah military intervention, and Turkish intervention as much against America’s Syrian Kurdish allies as against IS. The United States also may not have any clear civil-military program in Syria, but it has become one of the largest single aid donors, spending some $6 billion on humanitarian aid.10 It has effectively committed itself to open-ended humanitarian aid without any clear prospect of creating a state where that aid can go to help recovery and reconstruction.

Syria is Deeply Divided, and Syria’s Neighbors Present Further Critical Challenges

Syria is a grim study in just how important the civil dimension of war can be, and in just how difficult the challenge of stability operations (and nation building) can be in tactical, strategic, and grand strategic terms. Many argue that the United States could have intervened decisively early in the Syrian crisis and civil war, done so at acceptable risk, done so at much lower cost, and done so before Syria became a humanitarian disaster and before some three thousand to five thousand Syrian civilians were killed in the fighting. There are no reliable estimates of the seriously injured, but the numbers may well be higher.

USAID estimates provide all too clear a picture of Syrian suffering at a civil level, and highlight one aspect of the challenge of conducting stability operations. USAID estimates that there are 13.5 million people in need of humanitarian assistance in Syria in a country with a total remaining population of around 22 million. There are 6.1 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Syria, and U.S. aid is now critical to some 4 million people each month.11

No one has a full count of the number Syrian refugees outside Syria because many have stopped registering. Syrian refugees are, however, putting a far greater burden on neighboring states than on Europe or the token numbers that the United States may or may not admit. There are at least 4.8 million Syrian refugees in neighboring states: 2.7 million Syrian refugees in Turkey, 1 million Syrian refugees in Lebanon, 656,400 Syrian refugees in Jordan, and 225,500 Syrian refugees in Iraq.12

The situation inside Syria is already critical and is growing steadily worse. The United Nations (UN) Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) warned at the end of 2016 that—

Over half of the population has been forced from their homes, and many people have been displaced multiple times. Children and youth comprise more than half of the displaced, as well as half of those in need of humanitarian assistance. Parties to the conflict act with impunity, committing violations of international humanitarian and human rights law.

Among conflict-affected communities, life-threatening needs continue to grow. Neighboring countries have restricted the admission of people fleeing Syria, leaving hundreds of thousands of people stranded in deplorable conditions on their borders. In some cases, these populations are beyond the reach of humanitarian actors.

Civilians living in 13 besieged locations, 643,780 people in need of humanitarian assistance are denied their basic rights, including freedom of movement and access to adequate food, water, and health care. Frequent denial of entry of humanitarian assistance into these areas and blockage of urgent medical evacuations result in civilian deaths and suffering. 3.9 million people in need live in hard-to-reach areas that humanitarian actors are unable to reach in a sustained manner through available modalities.13

In the absence of a political solution to the conflict, intense and widespread hostilities are likely to persist in 2017. After nearly six years of senseless and brutal conflict, the outrage at what is occurring in Syria and what is being perpetrated against the Syrian people must be maintained. Now is the time for advocacy and now is the time for the various parties to come together and bring an end to the conflict in Syria.

U.S. Stability and Civil-Military Operations for Whom and for What

“Might have beens” are always studies in irrelevance. What these facts on the ground make all too clear is that today’s Syria is a steadily worsening and divided mess. The United States now seems to lack options for either security or stability, and the U.S. ability to link some kind of meaningful military operation to effective civil military operations, conflict termination, and reconstruction and recovery is dubious at best.

Syria’s problems go far beyond its humanitarian crises and simply trying to defeat one key enemy. Even if IS is largely defeated, large numbers of IS fighters are certain to escape and disperse, and Syria will still present extraordinarily difficult security and stability problems. Any broader ceasefire is likely to either collapse under the pressure of warring factions or see new power struggles in a divided Syria between elements of the Assad regime, the main Arab rebel factions that include large numbers of Islamist extremists, and the U.S.-backed Syrian Kurds.

The pro-Assad forces seem likely to win in the more populated areas in western Syria. Aleppo has fallen, and pro-Assad or Syrian Arab Republic forces dominate the populated areas of Western Syria with varying degrees of Russian, Iranian, and Hezbollah support and influence. Regime and allied forces have been responsible for the overwhelming majority of atrocities, civilian casualties, and collateral damage. At best, they can control and repress, but cannot bring lasting stability and unity.

No one can predict what will happen in eastern Syria or near the border with Iraq. While the Syrian Arab Republic forces try to preserve the image of unity in dealing with the outside world, there are serious divisions within them, and significant numbers of the current population are IDPs who have moved to obtain security and not because of any loyalty to the regime.

Eastern Syria is divided into competing and sometimes warring rebel, sectarian, and ethnic factions: the more secular and moderate Arab rebel factions in the Free Syrian Army, relatively more moderate Arab Islamist factions, and the largely Arab Islamist extremist factions in the Army of Conquest. There are also largely Kurdish forces in the Rojava region of northern Syria, along with the so-called Syrian Defense Forces. These forces predominantly consist of personnel from the Yekîneyên Parastina Gel (YPG, or the Kurdish People’s Protection Units). Estimates of their size range from forty thousand to seventy thousand fighters. While largely Kurdish, some estimates put the number of Arabs, Turkmens, Armenians, Assyrians, and other minorities as high as 40 percent of the fighters.

For all the talk of a “unified” Free Syrian Army, the Arab rebel movements are now deeply divided, and include large Islamic extremist elements like Jabhat Fatah al-Sham, Ahrar al-Sham, Fatah al-Islam, and Jordanian Salafi-jihadists. Many experts believe such extremist groups dominate the number of Arab fighters.

At the same time, the U.S.-backed Syrian Kurdish fighters pursue their own ethnic goals and territorial ambitions, with ties to the Partiya Karkerên Kurdistanê (PKK, or the Kurdistan Worker’s Party) in Turkey, and ties to the Kurds in Iraq. The key element in the Syrian Kurdish rebel force—the YPG—has proven to be the only effective rebel element in fighting IS. The YPG is the key U.S.-backed element in Syria—albeit with a strangely dysfunctional libertarian ideology that attempts to combine socialism with the views of social anarchists.

This has vastly complicated U.S. coordination with President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s government in Turkey, which sees the YPG as an ally to the PKK and a threat to Turkey. As Syria continued to deteriorate, Turkey became steadily more involved on a military level because of its own civil war with the Kurds within its own borders. Turkey desires to create a security zone in Syria on its southern border, and wants to keep Syria’s Kurds in the west divided from the Kurds in the east. Additionally, Erdoğan is using the war to help take a central role in governing Turkey by expanding his role as president to authoritarian levels.

So far, Ankara has been forced to temper its ambitions in the face of stiff resistance from IS fighters near al-Bab and from entrenched Kurdish forces in Manbij—two towns that are critical to the control of Aleppo Province and crucial for any future group operations against Raqqa, IS’s de facto capital. No one, however, can predict whether the Kurds will find some way to work with Arab Syrian rebels, the Turks, or other factions; how much U.S. civil and military aid they get and where; and how any stability and other civil aid will be provided. As of February 2017, the United States had made increases in the support it was providing by air, Special Forces, and other select combat elements, but it still had not decided on the military options for providing the Syrian Kurds and associated Arab forces with the weapons and support they needed to move on Raqqa.

All of these forces divide Syria along both military and civil fault lines. Virtually any form of victory against one faction tends to empower to remaining factions and lead to new forms of conflict. As for U.S. strategy, it was in a total state of flux at the time this analysis was written in early February. The Trump administration has made it clear that it does not endorse the military plans to strengthen U.S.-supported rebels forces in Syria formed under the Obama administration, but had not announced plans of its own. It did issue a presidential memorandum calling for a Plan to Defeat the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria.14 This memorandum, however, made no mention of any form of stability operations, any aspect of a civil campaign and effort to coordinate civil-military operations, or the need for resolve. Rather than deal with stability operations, or civil military affairs, the U.S. strategy called for in the text of the memorandum seemed to be one of “we’ll fight IS until we leave, and please don’t bother us with the end result.”

More broadly, the United States has never announced any plan or effort to use humanitarian aid and civil-military programs to try to stabilize the areas under Syrian Kurdish control and the rest of the border area near Iraq, find some modus vivendi between Syrian Kurd and Arab, and find a modus vivendi between Syria’s Kurds and Turkey. At least as of February, the Trump administration—like the Obama administration before it—has also failed to provide any indication of what it meant by talking about “safe zones,” although the new president has said on television that he “will absolutely do safe zones in Syria” for refugees fleeing violence in their country, devastated by years of civil war.15

So far, the United States has never came to grips with the real world civil-military problems in choosing locations for those safe zones and defining who such zones would protect. The Trump administration has not detailed how the sites could be secured in the air and on the ground; what kind of civilian facilities would be provided; how they would be resupplied; and what their structure and capacity structure could be in terms of the water, power, other infrastructure, education, and medical services needed by hundreds of thousands to millions of civilians.

What is all too clear, however, is that there is virtually no surplus housing, services, infrastructure, and the other essentials of stability operations anywhere in eastern Syria after more than a half decade of war. It is equally clear that almost any choice involves alienating some faction, possible attacks by the Assad regime, and possible attacks by Turkey, divided Kurdish factions, or hostile Arab rebel factions. There are all too many threats, both in the air and on the ground.

Leaving Syria’s Neighbors and its Border with Iraq without Either a Military or Civil Strategy

This vacuum in civil-military and stability operations goes much further than Syria. Syria’s other neighbors are forced to focus on their own security and stability. Israel must shape its own security and guard against a sweep of threats from under-governed or destabilized spaces, which include IS-linked Salafi-Jihadi threats in Egypt’s Sinai; potential instability tied to Hezbollah along the UN Blue Line with Lebanon; and threats on the Golan Heights from both Hezbollah and Iran’s Quds Force on the one hand, and al-Qaida affiliated groups on the other.

Lebanon and Jordan face similar challenges from potentially ungoverned and undergoverned spaces along their borders with Syria, and both—with U.S. and Western support—have responded by significantly expanding and reshaping their military’s border security and deterrence forces. Given their limited topography, smaller populations, and relatively weaker economies, Lebanon and Jordan also bear a disproportionately larger burden tied to the number of Syrian refugees.

The most critical problem from the viewpoint of classic stability operations, however, is that Iraq has an open and vulnerable border with Syria. It has its own Kurdish problems and has a deep division between its Sunni and Shiite populations. Even if the United States can avoid stability operations and a civil-military effort in most of Syria, it cannot defeat IS’s physical “caliphate” and ensure that no combination of other violent Islamist extremists that replace it can successfully challenge other neighboring states, or export terrorism, unless it takes such action.

In order to secure Iraq, the United States has to have a civil-military strategy for both eastern Syria and the border area with Iraq and Jordan. This strategy must ensure the defeat of IS in Syria as well as in Iraq, and it must make certain that the liberation of eastern Syria and western Iraq does not create a bloc of Sunni Arabs hostile to Syrian and Iraqi Kurds and the Iraqi central government. Such a strategy has to deal with civil stability and not simply with military security.

As of February 2017, the United States had not developed effective Arab rebel forces to defeat IS in Syria and had not given the Rojava, Syrian Defense Forces, or YPG the same mix of weapons, forward advisors, and combat support necessary to defeat IS in its Syrian capital in Raqqa. Neither the Obama nor the Trump administrations has ever made any unclassified statement of its overall strategy or plans for stability operations for dealing with the Iraqi border area and eastern Syria when—and if—IS is defeated, and the Obama administration left office without resolving any of the tension between Turkey and Syria’s Kurds.

The United States can solve part of this narrow “stability” problem by sustaining the present levels of aid to Iraq and by ensuring that Jordan and Lebanon can secure their borders with Syria. It must, however, work actively with the Iraqi central government to persuade it to provide the aid, support, political equity, and security to Iraqi Sunnis that will give them reason to be loyal to the Iraqi central government.

The United States may well have to broker some form of Syrian Kurdish security zone in Northeastern Syria that will give its Kurds and allied minorities the resources they need to preserve near-autonomy, and it may have to broker an arrangement with Turkey where it can accept that the Syrian Kurds will not actively back the PKK in the ongoing Turkish conflict. It may also have to work with Jordan and the Arab Gulf states to provide aid and resources to Arab Sunnis in the far east of Syria to limit Islamic extremist influence. This, however, is far easier to propose than to implement, and it is a further warning that successful operations in failed-state wars need both an integrated civil-military strategy and a civil effort that looks beyond the military dimension, humanitarian aid, and purely local and ephemeral stability operations.

The Ultimate Stability Challenge: Recovery and Reconstruction

It is far from clear how long the United States can avoid looking at the far more serious problem of recovery and reconstruction in Syria, both in terms of any broad form of conflict termination and creating any kind of lasting “victory.” As bad as the civil, governance, economic, and justice sectors are in Afghanistan and Iraq, Syria is truly a failed state in terms of governance, economic, and every aspect of recovery and reconstruction.

Estimates of the cost of reconstruction are highly uncertain, but estimates by World Vision and Frontier Economics have risen to over $275 billion today and indicate that the total could be over $1 trillion if the civil wars drag on to 2020.16 To put these kinds of figures in additional perspective, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) estimates that Syria’s GDP dropped by 70 percent between 2010 and 2016; it was only $24.6 billion in 2014 at the official exchange rate, and was only $55.8 billion in 2015, even in purchasing power parity terms. And, no one can begin to estimate what it will take to deal with what may well be a deeply divided country, to reduce corruption and misgovernment to workable levels, and to establish any stable pattern of income distribution and reconstruction efforts.17

The UN’s Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA) published a far more detailed study in November 2016, titled Survey of Economic and Social Developments in the Arab Region, 2015-2016. This study addressed the cost of the political upheavals and fighting in the Middle East and North Africa region that begin in 2011, and provided the following summary description of the longer-term cost of recovery and reconstruction in Syria.

Now in its sixth year, the Syrian civil war has led to one of the most severe humanitarian crises of the new millennium. The international community has failed to end the conflict or provide adequate aid. Recent estimates put the total death toll at 470,000.i The country’s population has decreased by one fifth, due to casualties and emigration. The war has been accompanied by atrocities, the rise of the so-called “Islamic State,” a regional and global refugee crisis, and external intervention that has only fueled hostilities.

The conflict has left a once middle-income economy in ruins. Various studies have been conducted on the impact of the war on the economy. However, official data have been scant since the war began and account only for activities in areas controlled by the Government. Data on other regions are more difficult to gather.

In this study, we make use of the most recent estimates of economic losses and look at potential post-war projections.

1. Pre-conflict situation and trajectory

According to the Government’s Eleventh Five-year Plan, GDP stood at $60.2 billion in 2010 and was set to grow steadily in the years to 2015 [Source: “Post-Conflict Challenges for the Macroeconomic Policies for Syria,” National Agenda for the Future of Syria (NAFS) (Beirut: ESCWA, 2016)]. Under the plan, public investment was to rise from SYP 309 billion to SYP 514 billion between 2011 and 2015, with major investments in public administration, transportation, water and electricity. In practice, those plans have been stripped back and funds have been diverted to military expenditure.

2. Impact of the conflict

According to NAFS estimations, the Syrian conflict has caused losses of $259 billion since 2011, including $169 billion from lost GDP as compared with pre-conflict projections, and $89.9 billion from accumulated physical capital loss. The Syrian Centre for Policy Research (SCPR) says that overall GDP loss has been three times the size of the country’s GDP in 2010.ii The degree of destruction has increased over time, and ramped-up bombing campaigns since late 2015 have begun targeting infrastructure and economically vital sectors such as energy, which had previously been largely immune. This will further diminish the productive capital stock left at the end of the war.

Building and industry have borne the brunt of destruction. Output of manufacturing, a key subsector for job and income creation and an indicator of economic transformation, now stands at one third of its 2010 level.

Despite farming losses, favorable weather, and the shift to smallholder agriculture during the conflict lifted agriculture’s share of GDP from 17.4 per cent before the crisis to 28.7 per cent in 2015. That has been matched by a fall in the GDP share of other sectors, particularly mining (an 11.6 percentage point drop) and internal trade (a 4.5 percentage point drop).iii Other subsectors, including tourism and utilities, have also been adversely affected.

Public and private sector consumption and investment continue to slide. Public consumption dropped by nearly one third from 2014 to 2015, and household consumption has fallen as consumer price index (CPI) inflation has risen.iv “Semi-public” consumption (that is, consumption in areas beyond the Government’s control) represented 13.2 per cent of GDP in 2015. For example, the so-called “Islamic State” controls three quarters of oil production.

Unemployment rose from 15 per cent in 2011 to 48 percent in 2014. Some three million Syrians, responsible for 12.2 million dependent family members, have lost their jobs during the course of the conflict.v More than 80 per cent of the Syrian population were living below the poverty line at the end of 2015, as opposed to 28 per cent in 2010.vi Areas with the highest poverty rates include Al-Raqqa, Idlib, Deir El Zor, Homs and the rural area around Damascus, all of which have witnessed some of the most brutal and prolonged battles of the conflict so far. The deep descent into poverty has been fueled by rising unemployment, the loss of property and assets by large numbers of IDPs and sharp cuts in food and fuel subsidies.

The continuing economic destruction will translate into a new lower level and trajectory for the Syrian economy, with greater dependence on imports and aid. Debt, unemployment, inflation and other negative indicators are all worsening, and any gains in terms of remittances and informal trade are vastly offset by the physical losses and opportunity costs of the war. So, although theory posits that countries in long-term conflict may adjust to the economic consequences, the situation in the Syrian Arab Republic is worsening every year according to most economic indicators.

The conflict has triggered an unprecedented refugee crisis. The plight of refugees has been documented but global humanitarian assistance and legal allowances for displaced persons remain inadequate. Under an agreement reached in London between European and Arab partners in February 2016, it was decided to open markets for manufactured goods, such as textiles, from Jordan because of the refugee burden that country is bearing.vii According to the ILO, 28 per cent of Syrian refugees in Jordan had work in early 2014. Unemployment in that country had, however, soared from 14.5 per cent in March 2011 to 22 per cent in 2014.18

The study goes on to describe the high cost of the war to Syria’s neighbors and the impact of its refugee issues on their economies. It then summarizes the key conclusions of an economic model for reconstruction that assumes a full and immediate solution to the conflict, national unity, and massive outside investment and aid.

The NAFS scenario for rebuilding the economy of the Syrian Arab Republic, supposing that hostilities will end in 2016, uses a financial programming model to calculate what will be needed to return the country’s GDP to its 2010 level by 2025.

… Under the scenario, a minimum public investment of $183.5 billion will be needed to rebuild the country. This equals the sum of cumulative capital loss during the conflict and the investments intended under the 2011 five-year plan, and will boost growth through multiplier effects and stimulate private investment.

… Reconstruction could be divided into two phases … a peacebuilding phase (2016-2018), with a focus on basic needs, ending violence and initiating economic recovery, and a State-building phase (2019-2025), expanding investments to productive sectors and activities, with sectoral allocations presumably based on the five-year plan. The process will require major and expanding investment, particularly from the private sector. Success will depend greatly on the sources and reliability of, and conditions attached to, the available financing options.

An alternative exercise utilizes a computable general equilibrium (CGE) model, based on the assumption that hostilities end in 2016 and implementation of Eleventh National Development Plan, with a focus on rebuilding destroyed capital and restoring public investment.viii

This yields interesting projections, including a steady increase in GDP similar to the NAFS calculations, but with a spike of 40.6 percent GDP growth in 2016 due to the immediate infusion of capital and assistance, before it levels off to an average of between 11 and 15 percent. Capital stock would grow at its pre-crisis rate to reach 2011 levels by 2017 in an optimistic projection. Public investment would spike in 2016 and continue to grow as well, triggering private sector investment. Exports would increase slowly, reaching a value of 20 percent of GDP by 2020, while imports would boom at 57 percent of GDP in 2016, later stabilizing at 43 percent. In the absence of grants, the public deficit and debt would increase to 50 and 200 percent of GDP respectively. This highlights the importance of tapping into a broad range of alternative financing options. With so many Syrians displaced externally, remittances will play an important role in rebuilding as many of those who find work will remain abroad and continue to work and send money home.

Post-conflict macroeconomic policy will have to go beyond stabilization and tackle problems resulting from the loss of physical and human capital, brain drain, deep political and geographical divisions, as well as factoring in peacebuilding. The approach to post-war reconstruction in Lebanon offers some cautionary lessons. The economic policies and political arrangements arrived at, although they helped the country to emerge from conflict, did not prove sustainable in the longer term.19

The IMF has issued a series of assessments of the impact of Syrian conflict and the problems it creates for reconstruction. One such assessment was issued in June 2016, and it joins the UN study in warning just how serious the recovery and reconstruction challenge is, although the IMF study seems less optimistic than the UN ESCWA study about the speed with which recovery is possible:

The conflict has set the country back decades in terms of economic, social, and human development. Syria’s GDP today is less than half of what it was before the war started. Inflation is high double digits, and there has been a large depreciation of the exchange rate. International reserves have been depleted to finance large fiscal and current account deficits, while public debt has more than doubled. Syria’s people are struggling with the devastating effects of the conflict, including widespread unemployment and poverty, homelessness, food and medicine shortages, and destruction of public services and infrastructure. The situation for those who have stayed in Syria is dire: half of the population is displaced, the social fabric is torn, many children are no longer schooled, access to medicine, food and clean water is limited, and many people of all ages are traumatized by the war.

Rebuilding the country will be a complex and monumental task. Reconstructing damaged physical infrastructure will require substantial international support and prioritization. Rebuilding Syria’s human capital and social cohesion will be an even greater and lasting challenge. Considerable resources will need to go to rebuilding the lives of internally displaced people, and to encouraging the return and reintegration of refugees along with reducing the divisions and tensions between various sectarian communities. Far-reaching economic reforms will be needed to create stability, growth, and job prospects. The immediate focus would need to be on urgent humanitarian assistance, restoring macroeconomic stability and rebuilding institutional capacity to implement cohesive and meaningful reforms. In the medium term, the reform agenda could include diversifying the economy, creating jobs for the young and displaced, tackling environmental issues, and addressing long-standing issues such as the regional disparities in income and greater political and social inclusion.20

Key points in the IMF study include:

Many factors will determine the extent and speed of rebuilding the country. Most importantly, the timeframe and success of any reconstruction will hinge on when and how the conflict is resolved. This, in turn, will shape the scope and pace of political and economic reforms. And it will determine how much external assistance is forthcoming, including whether Syria will be able to attract private investment. It will be critical to establish quick wins, including in the energy sector and agriculture, as well as in labor intensive industries such as textile or food processing, which could become drivers of growth.

The recovery will likely take a long time. The literature on post-conflict recovery shows that a longer-lasting conflict will have a more negative impact on the economy and institutions, and prolong the recovery.ix For instance, it took Lebanon, which experienced 16 years of conflict, 20 years to catch up to the real GDP level it enjoyed before the war, while it took Kuwait, which endured two years of conflict, seven years to regain its pre-war GDP level. Given the unprecedented scale of devastation, it may be difficult to compare Syria with other post conflict cases. That said, if we hypothetically assume that for Syria the post-conflict rebuilding period will begin in 2018 and the economy grows at its trend rate of about 4 1/2 percent, it would take the country about 20 years to reach its pre-war real GDP level.x Achieving a higher growth rate would allow the country to achieve a faster recovery.xi This assumes that the country can quickly restore its production capacity and human capital levels and remains intact as a sovereign territory. Any break-up of the country would affect potential growth and might require creating new institutions and governance structures.

Rebuilding damaged physical infrastructure will be a monumental task, with reconstruction cost estimates in the range of $100 to $200 billion. SCPR estimates that the destruction of physical infrastructure between 2011 and 2014 amounted to US$72–75 billion, equivalent to about 120 percent of 2010 GDP. The MPMR estimated in early 2015 that the conflict has cost the oil industry alone US$27 billion from the destruction of wells, pipelines, and refineries.xii Similarly, the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) suggests that it will take years for Syrian’s domestic energy system to return to its pre-conflict operating status, even after the conflict subsides. xiii With the escalation of the conflict since the second half of 2015, the rebuilding estimates are likely to be much higher. More recently, the UN Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA) estimated that Syria would require about $180 to $200 billion—three times the 2010 GDP.xiv

Syria will also have to grapple with deep-rooted socioeconomic challenges. The extreme rise in mass poverty, destruction of health and education services, and large-scale displacement of Syrians will pose huge challenges. Syria’s population has shrunk by 20–30 percent, with 50 percent of the population internally displaced, destroyed homes, and many highly skilled workers and entrepreneurs having left the country. Moreover, the currently low school enrollment rate of children will negatively impact the country’s potential output for years to come. SCPR estimated in 2014 that the loss of years of schooling by children represents a human capital deficit of $5 billion in education investment. A recent United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) report placed the loss in human capital at $10.5 billion from the loss of education of Syrian children and youth.xv Many children have been born into conflict and exposed to violence, and studies show that exposure to violent conflicts has long-term effects on generations to come. Therefore, considerable resources will need to go to rebuilding the lives of internally displaced people, and to encouraging the return and reintegration of refugees. Further, the conflict has exacerbated existing, and created new, divisions and tensions between various sectarian communities across the country that will need to be addressed in a meaningful way to promote social and political cohesion.21

The IMF study focuses on the IMF’s mission, and fiscal reform and stability as the path to recovery and reconstruction. It notes that there are serious problems in getting the data needed for even an assessment, and its reform suggestions give priority to fiscal issues over political needs and conflict resolution. At the same time, the study makes it make it clear that there is a very real political and human dimension:

The post-conflict reconstruction efforts should seek to address regional disparities in income and social inclusion. Poverty and extreme poverty, according to SCPR, have worsened further with the conflict, and are highest in governorates that have been most affected by the conflict and that were historically the poorest in the country. Addressing the underpinnings of these disparities should be central to any policy package intended to bring about peace and prosperity. Innovative approaches will be required to improve the provision of public services, including reconstruction of damaged water pipelines, farm irrigation and drainage, roads, schools and hospitals, employment prospects, and access to finance at the regional levels. Institutional and governance arrangements should be considered to give local authorities greater controls over service delivery, including greater forms of fiscal decentralization.xvi However, for fiscal decentralization to work, certain critical governance conditions will need to be in place, including ensuring local authorities are held accountable and resources are spent in a transparent manner. Therefore, any decentralization efforts have to take into account Syria’s new governance model, as well as the state of its institutions.

Rebuilding public institutions and improving governance will be key. This includes making fiscal policy and fiscal management effective, fair, and transparent; developing the rule of law and judiciary independence; and re-establishing and strengthening the capacity for monetary operations and banking supervision, and reforming the bank regulatory framework, including the anti-money laundry and combating terrorist financing (AML/CFT) regime. xvii These efforts would help address governance issues that plagued the country prior to the start of the conflict and contributed to regional and income disparities, and that likely have further deteriorated. They would also help facilitate the re-integration of the domestic financial system into the global economy, lower transaction costs, and reduce the size of the informal sector. Lessons from other post conflict countries show that framing an overall consistent technical assistance strategy at the outset of the post-conflict phase and securing donor coordination are critical for successful implementation of economic and institutional reforms.22

The World Bank has also addressed the challenge of Syrian recovery and reconstruction. Its work also highlights the sheer scale of the recovery and reconstruction effort that will be needed, and an October 2016 update of its work highlights and updates its assessments of several important issues:

The conflict has had severe macroeconomic implications. Real GDP contracted sharply in 2012-15, including some 12 percent in 2015. After increasing by nearly 90 percent in 2013, inflation eased but remained high at nearly 30 percent in 2014-15. The severe decline in oil receipts since the second half of 2012 and disruptions of trade due to the conflict has put pressure on the balance of payments and the exchange rate. Revenues from oil exports decreased from US$4.7 billion in 2011 to an estimated US$0.14 billion in 2015 as most of Syria’s oil fields are outside government control. The current account deficit reached 19 percent of GDP in 2014 but declined markedly to 8 percent of GDP in 2015. International reserves declined from US$20 billion at end-2010 to US$1.1 billion at end-2015, while the Syrian pound depreciated from 47 pounds per USD in 2010 to 517 pounds per USD at end-August 2016. The overall fiscal deficit increased sharply, reaching 20 percent of GDP in 2015, with revenues falling to an all-time low of below 7 percent of GDP during 2014-15 due to a collapse of oil and tax revenues. In response, the government cut spending, including on wages and salaries, but this was not enough to offset the fall in revenues and higher military spending.

Macroeconomic and poverty projections are complicated by the uncertainty about the duration and severity of the conflict. Nevertheless, real GDP is estimated to continue to contract in 2016 by around 4 percent on account of a worsening of the conflict in key centers of economic activity such as Aleppo and as oil and gas production and non-oil economic activity continue to suffer from the conflict. Inflation is likely to remain very high at around 25 percent in 2016, because of continued ex-change rate depreciation, trade disruptions, and shortages. Current account and fiscal deficits are also projected to remain large, broadly around the levels of 2015. Medium-term macroeconomic prospects hinge on containing the war and finding a political resolution to the conflict, and rebuilding the damaged infrastructure and social capital.

The key challenges are clearly to end the conflict and restore basic public services along with other measures to address the humanitarian crisis.23

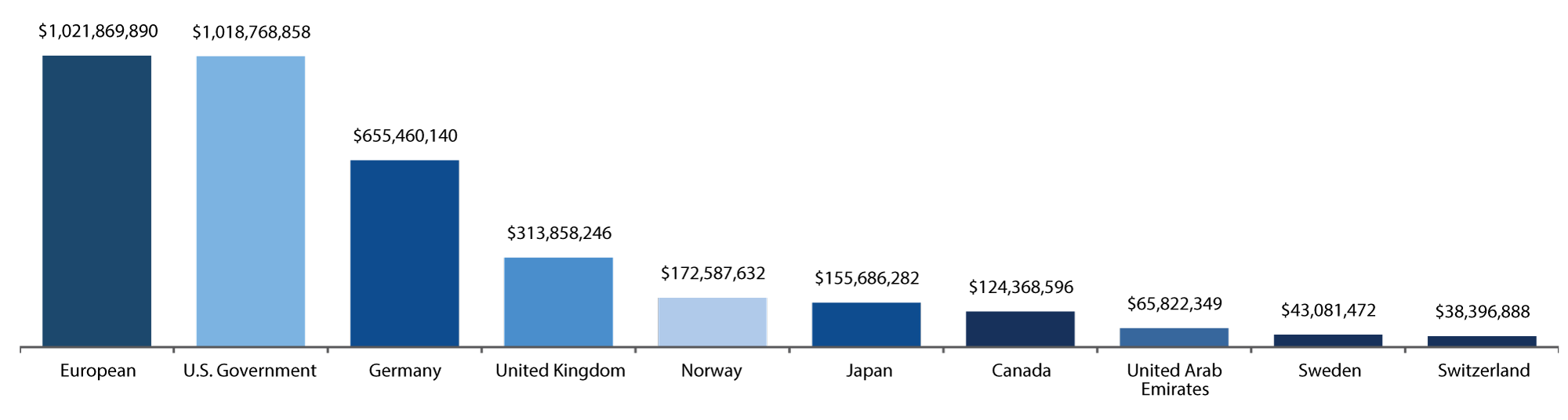

Funding figures are as of 13 July 2016. All international figures are according to the United Nation’s Financial Tracking Service and based on international commitments during the current calendar year, while U.S. Government (USG) figures are according to the USG and reflect the most recent USG commitments based on the fiscal year, which began on 1 October 2015.

As horrifying as the potential human cost of failing to address these issues would be, the practical costs in dollars of any recovery and reconstruction effort to put Syria back on the path to recovery after any successful conflict resolution would present a massive potential drain on global international aid for a country with otherwise limited strategic importance to the United States.

Such an effort would also force outside powers to go far beyond some narrow definition of stability operations and fully address the issue of nation building. Moreover, the previous studies only deal with the current size of the problem. As long as the fighting and large-scale instability persist, Syria will continue to deteriorate and the suffering of the Syrian people will increase. Here again, it is critical to understand that short-term goals do not solve any key problems. A cease-fire is not a substitute for peace, nor a base for recovery and reconstruction.

Syria may lack a meaningful stable base for recovery and reconstruction even if the Assad regime and rebels can agree on halting the fighting; if the Assad government, Russia, Iran, Turkey, and key factions including Hezbollah can agree on their respective roles in western Syria; and if the different Arab rebel factions and Kurds can agree on areas of control, some form of federation, or some form of independence in eastern Syria. None of these options necessarily creates an effective structure of governance or economy, deals with the refugee and IDP problem, or offers any clear path to recovery and a return to development.

This leaves the United States with very limited grand strategic options to deal with the most important single challenge in stability operations. One U.S. option is to try to dodge the issue of creating some form of stability operations that can create a basis for postconflict recovery and reconstruction entirely by taking the position that Russian, Iranian, and Turkish military interventions in Syria create responsibility by these countries for taking the lead in aid, recovery, and reconstruction. This option reflects real-world U.S. strategic priorities.

This option also reflects the reality that the de facto division of the country and survival of the Assad regime—whose past record for governance, development, and corruption led to the upheavals that began in 2011—make effective reform and reconstruction dubious prospects at best. From a humanitarian viewpoint, however, the crisis in Syria is so great that there is a strong moral and ethical case for intervention regardless of U.S. strategic priorities. However, from a practical, or “realist,” view point, that argument only applies if some form of intervention can clearly work, if there is enough governance and stability to ensure that aid is used effectively, and if intervention and aid help all of Syria’s people—not just some faction or sectarian and ethnic group.

At the same time, the United States cannot ignore the real-world problems of trying to support lasting conflict resolution and nation building. Throwing good money at bad leaders will not serve either strategic or humanitarian interests, and aiding some factions or excluding other does not lay the groundwork for stability and lasting peace. The Assad regime is, and always has been, a bad government. The World Bank governance indicators reflect a long history of incompetence by the government of the Syrian Arab Republic (the Assad regime) in all six measures of governance and shows its capabilities have crashed to the bottom of the world since 2011.24

The World Bank’s six measures include voice and accountability, political stability and the absence of violence, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law, and control of corruption.25 All six focus on practical governance and not on more idealistic values like human rights and democracy. About the most that can be said for the Assad regime is that the World Bank has rated Afghanistan, Iraq, and Yemen as near the bottom of world performance as Syria during the entire period from 1996-2015, regardless of changes in regime during this period and U.S. aid and nation-building efforts.26 A look at CIA, UN, IMF, Arab Human Development, and World Bank economic development and governance reports over the period from 2000 to 2016 for Syria—and for Afghanistan, Iraq, and Yemen—reveals the same broad patterns. “Failed-state wars” is not an exaggeration: host governments really can be as much of a threat as the enemy, insurgencies do have major material as well as ideological causes, and the civil dimensions of war really are critical.

As a result, the United States has two more positive real-world options for this far broader aspect of stability operations. One is to concentrate solely on the more limited kinds of humanitarian aid that pass through international hands and help ordinary Syrians regardless of their location, faction, sect, or ethnic background, and to press other states to provide such aid as well.

As has been noted earlier, USAID reports that the United States has allocated some $6 billion in such aid as of January 2016, and the figure (page 17) shows that there are many other donors.27 The USAID report is further backed up by the data provided by OCHA as depicted in tables 1 (page 18) and 2.28 Providing such aid through bodies like the UN’s OCHA, the International Syria Support Group Humanitarian Assistance Task Force, the Syrian Arab Red Crescent, and the UN World Food Programme bypasses both the Syrian government and rebel factions and can achieve significant humanitarian goals.

Such humanitarian aid does not meet more lasting needs like recovery and development, but it is far from clear that there is a credible option for such action. In contrast, there are many different countries providing direct humanitarian aid to Syria and to Syrian refugees. The figure (page 17) does make it clear that the U.S. share of such aid is likely to be relatively large, and any contributions by Russia and Iran may be slow to come if ever. Such choice does not tie the United States to what may be “mission impossible” for years to come, or make the United States seem responsible for a Syria that will not or cannot help itself.

A second, and more positive, option reflects both the real-world limits of outside nation-building efforts that became all too clear in Afghanistan and Iraq, and the real-world limits imposed by U.S. politics and public willingness to repeat the immense cost and waste that occurred in both countries. The U.S. public and Congress might accept a major U.S. contribution to the equivalent of an international Marshall Plan—a plan in which other states pay a very substantial part of the cost, clear conditions are laid down for allocating the money with clearly defined auditing and measures of effectiveness, and the administration and support was accomplished by a competent international body with real integrity like the IMF or the World Bank.29

Although the U.S. government has already shown it lacks both the will and the competence to implement such a plan, as was the case with the original Marshall Plan, even putting such an option on the table could have a powerful effect in bringing civil stability and creating some incentive for a real peace. The plan could also be offered to other conflict states with funding awarded on a competitive basis.

One thing is all too clear, however, from both a Syrian case study and the related lessons of Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, and Yemen. Revolutions in military affairs are not a substitute for revolutions in civil-military affairs. Being the best warfighter in the world is not enough. Neither is treating stability operations and civil-military affairs as a sideshow. Grand strategy means shaping the way in which wars end and their aftermath, not simply defeating the enemy.

Notes

- Department of Defense (DOD) Instruction Number 3000.05, Stability Operations, 16 September 2009, accessed 8 February 2017, http://www.dtic.mil/whs/directives/corres/pdf/300005p.pdf.

- Ibid., 1.

- Ibid., 2-3.

- U.S. Army Field Manual 3-07, Stability (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Publishing Office, 2014), accessed 8 February 2017, http://pksoi.army.mil/default/assets/File/fm3_07(1).pdf.

- DOD Instruction Number 2000.13, Civil Affairs, 11 March 2014, accessed 8 February 2017, http://www.dtic.mil/whs/directives/corres/pdf/200013_2014_correction_b.pdf.

- Defense Science Board, Transition To and From Hostilities (Washington, DC: Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics, December 2004), iv, accessed 8 February 2017, http://www.acq.osd.mil/dsb/reports/ADA430116.pdf.

- Ibid., app. D.

- Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, Biennial Assessment of Stability Operations Capabilities, February 2012, https://publicintelligence.net/ufouo-dod-stability-operations-capabilities-assessment-2012/.

- John F. Sopko, High-Risk List, Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction report, January 2017, accessed 27 February 2017, https://www.sigar.mil/pdf/spotlight/2017_High-Risk_List.pdf; “Program Note: Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, International Monetary Fund website, last updated 11 April 2016, accessed 27 February 2017, http://www.imf.org/external/np/country/notes/afghanistan.htm; Omar Joya et al., Afghanistan Development Update, World Bank report, April 2016, accessed 27 February 2017, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/953921468196145402/Afghanistan-development-update.

- U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), “Syria Complex Emergency – Fact Sheet #5,” 30 September 2016, accessed 10 February 2017, https://www.usaid.gov/crisis/syria/fy16/fs05.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- “About the Crisis,” United Nations (UN) Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) website, accessed 10 February 2017, http://www.unocha.org/syrian-arab-republic/syria-country-profile/about-crisis; “Syrian Arab Republic: Overview of Hard-to-Reach and Besieged Locations (as of 26 Jan 2016),” ReliefWeb website, accessed 10 February 2017, http://www.reliefweb.int/map/syrian-arab-republic/syrian-arab-republic-overview-hard-reach-areas-and-besieged-communities-26.

- Office of the Press Secretary, Presidential Memorandum Plan to Defeat the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, The White House website, 28 January 2017, accessed 13 February 2017, https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2017/01/28/plan-defeat-islamic-state-iraq.

- Tim Lister, “Trump Wants ‘Safe Zones’ Set Up in Syria. But Do They Work?” CNN website, 27 January 2017, accessed 13 February 2017, http://www.cnn.com/2017/01/27/middleeast/trump-syria-safe-zone-explained/.

- Frontier Economics and World Vision International, The Cost of Conflict for Children: Five Years of the Syria Crisis, World Vision International website, 7 March 2016, 1, accessed 22 February 2017, http://www.wvi.org/syriacostofconflict.

- “Syria,” World Factbook, Central Intelligence Agency website, last updated 12 January 2017, accessed 13 February 2017, https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/syria/.

- UN Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia, Survey of Economic and Social Developments in the Arab Region 2015-2016 (Beirut: UN, November 2016), 83–85, accessed 13 February 2017, https://www.unescwa.org/sites/www.unescwa.org/files/publications/files/survey-economic-social-development-arab-region-2015-2016-english.pdf. Notes from original document identified in roman numerals: (i) Rabie Nasser et al., “Confronting Fragmentation—Impact of Syrian Crisis Report 2015, Syrian Centre for Policy Research, February 2016, accessed 13 February 2017, http://scpr-syria.org/publications/policy-reports/confronting-fragmentation/; (ii) Ibid.; (iii) Ibid.; (iv) Ibid.; (v) Ibid.; “Overview, Syria,” The World Bank website, 2015, accessed 13 February 2017, http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/syria/overview; (vi) Khalid Abu-Ismail et al., “Five Years Syria at War,” ESCWA and University of St. Andrews, 2016, accessed 13 February 2017, https://www.unescwa.org/sites/www.unescwa.org/files/publications/files/syria-war-five-years.pdf; (vii) “Syrian Refugees in Jordan: Peace, Bread, and Work,” The Economist, 5 May 2016, accessed 13 February 2017, http://www.economist.com/news/middle-east-and-africa/21698260-jobs-syrian-refugees-help-them-and-their-hosts-and-slow-their-exodus-peace.

- Ibid., 96-98. Notes from original document identified in roman numerals: (viii) Abdallah al-Dardari and Mohamed Hedi Bchir, “Assessing the Impact of the Conflict on the Syrian Economy and Looking Beyond,” United Nations report, 2014, accessed 13 February 2017, http://haqqi.info/en/haqqi/research/assessing-impact-conflict-syrian-economy-and-looking-beyond.

- Jeanne Gobat and Kristina Kostial, IMF Working Paper: Syria’s Conflict Economy, International Monetary Fund website, June 2016, 23-24, accessed 13 February 2017, http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2016/wp16123.pdf.

- Ibid., 19–20. Excerpted and adapted from Syria’s Conflict Economy. Notes from original document identified in roman numerals: (ix) Randa Sab “Economic Impact of Selected Conflicts in the Middle East: What Can We Learn from the Past?” IMF Working Paper No. 14/100 (Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund [IMF], 2014); (x) [This assumes] a peace agreement and new government are in place by the end of 2017 and that conditions permit investors and international donors to safely engage in the country’s rebuilding efforts. [Regarding economic growth], this is a conservative assumption. The catching up could be faster if in the immediate post conflict reconstruction phase, international financial assistance is large and there is capacity to implement the reconstruction strategy; (xi) With a one-standard deviation higher growth rate relative to trend, it would take Syria ten years to catch up to 2010 GDP levels; (xii) This figure includes the cost of looting and the foregone revenue from significantly lower production levels. According to MPMR, many oil wells in areas not under state control have been set on fire; (xiii) “Syria,” U.S. Energy Information Administration Beta website, accessed 14 February 2017, http://www.eia.gov/beta/international/analysis.cfm?iso=SYR; (xiv) Bassem Awadallah, “The Challenge of a New Regional Political Economy,” Huffington Post website, 21 May 2015, accessed 14 February 2017, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/bassem-awadallah/the-challenge-of-a-new-regional-political-economy-_b_7348502.html; (xv) “Economic Loss from School Dropout Due to the Syria Crisis: A Cost-Benefit Analysis of the Impact of the Syria Crisis on the Education Sector,” UNICEF report, December 2015, accessed 14 February 2017, http://allinschool.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Cost-benefit_analysis_report_English_final.pdf.

- Ibid., 22-23. Notes from original document identified in roman numerals: (xvi) Ehtisham Ahmad and Adnan Mazarei, “Can Fiscal Decentralization Help Resolve Regional Conflicts in the Middle East?” IMF blog, January 2015, accessed 14 February 2017, http://www.imf.org/external/np/blog/nafida/012315.pdf; (xvii) “Rebuilding Fiscal Institutions in Post-Conflict Countries,” IMF report, 10 December 2004, accessed 14 February 2017, http://www.imf.org/external/np/fad/2005/022505.htm.

- “Syrian Arab Republic,” World Bank report, October 2016, accessed 14 February 2017, http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/925291475460799367/Syria-MEM-Fall-2016-ENG.pdf.

- “Worldwide Governance Indicators,” World Bank website, 1996-2015, accessed 22 February 2017, http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/#home.

- Ibid.

- “Worldwide Governance Indicators—Interactive Data Access,” World Bank website, 1996-2015, accessed 22 February 2017, http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/#reports.

- “Syria–Complex Emergency: Fact Sheet #4, Fiscal Year (FY) 2016,” USAID website, 13 July 2016, accessed 22 February 2017, https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1866/07.13.16-USGSyriaComplexEmergencyFactSheet04.pdf.

- “Financial Tracking Service: Tracking Humanitarian Aid Flows,” UN OCHA website, as of 17 January 2017, accessed 27 February 2017, https://ftsarchive.unocha.org/pageloader.aspx?page=emerg-emergencyDetails&emergID=16589.

- The Marshall Plan was a large-scale economic recovery program to help Western European countries rebuild after World War II. The United States contributed over $12 billion over the four years the program was in effect. Funds were distributed on a per capita basis.

Anthony H. Cordesman is the Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy Emeritus at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). During his time at CSIS, Cordesman has been director of the Gulf Net Assessment Project and the Gulf in Transition Study, as well as principal investigator of the CSIS Homeland Defense Project. He has led studies on national missile defense, asymmetric warfare and weapons of mass destruction, and critical infrastructure protection. He directed the CSIS Middle East Net Assessment Project and codirected the CSIS Strategic Energy Initiative. He is the author of a wide range of studies on U.S. security policy, energy policy, and Middle East policy and has served as a consultant to the Departments of State and Defense during the Afghan and Iraq wars. He served as part of Gen. Stanley McChrystal’s civilian advisory group during the formation of a new strategy in Afghanistan and has since acted as a consultant to various elements of the U.S. military and NATO.