Learning Counterinsurgency:

Observations from Soldiering in Iraq

Lieutenant General David H. Petraeus, U.S. Army

Original article published in January-February 2006

Download the PDF

The Army has learned a great deal in Iraq and Afghanistan about the conduct of counterinsurgency operations, and we must continue to learn all that we can from our experiences in those countries.

The insurgencies in Iraq and Afghanistan were not, in truth, the wars for which we were best prepared in 2001; however, they are the wars we are fighting and they clearly are the kind of wars we must master. America’s overwhelming conventional military superiority makes it unlikely that future enemies will confront us head on. Rather, they will attack us asymmetrically, avoiding our strengths—firepower, maneuver, technology—and come at us and our partners the way the insurgents do in Iraq and Afghanistan. It is imperative, therefore, that we continue to learn from our experiences in those countries, both to succeed in those endeavors and to prepare for the future.

Soldiers and Observations

Writing down observations and lessons learned is a time-honored tradition of Soldiers. Most of us have done this to varying degrees, and we then reflect on and share what we’ve jotted down after returning from the latest training exercise, mission, or deployment. Such activities are of obvious importance in helping us learn from our own experiences and from those of others.

In an effort to foster learning as an organization, the Army institutionalized the process of collection, evaluation, and dissemination of observations, insights, and lessons some 20 years ago with the formation of the Center for Army Lessons Learned.1 In subsequent years, the other military services and the Joint Forces Command followed suit, forming their own lessons learned centers. More recently, the Internet and other knowledge-management tools have sped the processes of collection, evaluation, and dissemination enormously. Numerous products have already been issued since the beginning of our operations in Afghanistan and Iraq, and most of us have found these products of considerable value as we’ve prepared for deployments and reviewed how different units grappled with challenges our elements were about to face.

For all their considerable worth, the institutional structures for capturing lessons are still dependent on Soldiers’ thoughts and reflections. And Soldiers have continued to record their own observations, particularly in recent years as we have engaged in so many important operations. Indeed, my own pen and notebook were always handy while soldiering in Iraq, where I commanded the 101st Airborne Division during our first year there (during the fight to Baghdad and the division’s subsequent operations in Iraq’s four northern provinces), and where, during most of the subsequent year-and-a-half, I helped with the so-called “train and equip” mission, conducting an assessment in the spring of 2004 of the Iraqi Security Forces after their poor performance in early April 2004, and then serving as the first commander of the Multi-National Security Transition Command-Iraq and the NATO Training Mission-Iraq.

What follows is the distillation of a number of observations jotted down during that time. Some of these observations are specific to soldiering in Iraq, but the rest speak to the broader challenge of conducting counterinsurgency operations in a vastly different culture than our own. I offer 14 of those observations here in the hope that others will find them of assistance as they prepare to serve in Iraq or Afghanistan or in similar missions in the years ahead.

Observations from Soldiering in Iraq

| |

|

|

|

- “Do not try to do too much with your own hands.”

- Act quickly, because every Army of liberation has a half-life.

- Money is ammunition.

- Increasing the number of stakeholders is critical to success.

- Analyze “costs and benefits” before each operation.

- Intelligence is the key to success.

- Everyone must do nation-building.

- Help build institutions, not just units.

- Cultural awareness is a force multiplier.

- Success in a counterinsurgency requires more than just military operations.

- Ultimate success depends on local leaders.

- Remember the strategic corporals and strategic lieutenants.

- There is no substitute for flexible, adaptable leaders.

- A leader’s most important task is to set the right tone.

|

Fourteen Observations

Observation Number 1 is “Do not try to do too much with your own hands.” T.E. Lawrence offered this wise counsel in an article published in The Arab Bulletin in August 1917. Continuing, he wrote: “Better the Arabs do it tolerably than that you do it perfectly. It is their war, and you are to help them, not win it for them. Actually, also, under the very odd conditions of Arabia, your practical work will not be as good as, perhaps, you think it is. It may take them longer and it may not be as good as you think, but if it is theirs, it will be better.”2

Lawrence’s guidance is as relevant in the 21st century as it was in his own time in the Middle East during World War I. Like much good advice, however, it is sometimes easier to put forward than it is to follow. Our Army is blessed with highly motivated Soldiers who pride themselves on being action oriented. We celebrate a “can do” spirit, believe in taking the initiative, and want to get on with business. Yet, despite the discomfort in trying to follow Lawrence’s advice by not doing too much with our own hands, such an approach is absolutely critical to success in a situation like that in Iraq. Indeed, many of our units recognized early on that it was important that we not just perform tasks for the Iraqis, but that we help our Iraqi partners, over time enabling them to accomplish tasks on their own with less and less assistance from us.

Empowering Iraqis to do the job themselves has, in fact, become the essence of our strategy—and such an approach is particularly applicable in Iraq. Despite suffering for decades under Saddam, Iraq still has considerable human capital, with the remnants of an educated middle class, a number of budding entrepreneurs, and many talented leaders. Moreover, the Iraqis, of course, know the situation and people far better than we ever can, and unleashing their productivity is essential to rebuilding infrastructure and institutions. Our experience, for example, in helping the Iraqi military reestablish its staff colleges and branch-specific schools has been that, once a good Iraqi leader is established as the head of the school, he can take it from there, albeit with some degree of continued Coalition assistance. The same has been true in many other areas, including in helping establish certain Army units (such as the Iraqi Army’s 9th Division (Mechanized), based north of Baghdad at Taji, and the 8th Division, which has units in 5 provinces south of Baghdad) and police academies (such as the one in Hillah, run completely by Iraqis for well over 6 months). Indeed, our ability to assist rather than do has evolved considerably since the transition of sovereignty at the end of late June 2004 and even more so since the elections of 30 January 2005. I do not, to be sure, want to downplay in the least the amount of work still to be done or the daunting challenges that lie ahead; rather, I simply want to emphasize the importance of empowering, enabling, and assisting the Iraqis, an approach that figures prominently in our strategy in that country.

Observation Number 2 is that, in a situation like Iraq, the liberating force must act quickly, because every Army of liberation has a half-life beyond which it turns into an Army of occupation. The length of this half-life is tied to the perceptions of the populace about the impact of the liberating force’s activities. From the moment a force enters a country, its leaders must keep this in mind, striving to meet the expectations of the liberated in what becomes a race against the clock.

This race against the clock in Iraq has been complicated by the extremely high expectations of the Iraqi people, their pride in their own abilities, and their reluctant admission that they needed help from Americans, in particular.3 Recognizing this, those of us on the ground at the outset did all that we could with the resources available early on to help the people, to repair the damage done by military operations and looting, to rebuild infrastructure, and to restore basic services as quickly as possible—in effect, helping extend the half-life of the Army of liberation. Even while carrying out such activities, however, we were keenly aware that sooner or later, the people would begin to view us as an Army of occupation. Over time, the local citizenry would feel that we were not doing enough or were not moving as quickly as desired, would see us damage property and hurt innocent civilians in the course of operations, and would resent the inconveniences and intrusion of checkpoints, low helicopter flights, and other military activities. The accumulation of these perceptions, coupled with the natural pride of Iraqis and resentment that their country, so blessed in natural resources, had to rely on outsiders, would eventually result in us being seen less as liberators and more as occupiers. That has, of course, been the case to varying degrees in much of Iraq.

The obvious implication of this is that such endeavors—especially in situations like those in Iraq—are a race against the clock to achieve as quickly as possible the expectations of those liberated. And, again, those expectations, in the case of Iraqi citizens, have always been very high indeed.4

Observation Number 3 is that, in an endeavor like that in Iraq, money is ammunition. In fact, depending on the situation, money can be more important than real ammunition—and that has often been the case in Iraq since early April 2003 when Saddam’s regime collapsed and the focus rapidly shifted to recon-struction, economic revival, and restoration of basic services. Once money is available, the challenge is to spend it effectively and quickly to rapidly achieve measurable results. This leads to a related observation that the money needs to be provided as soon as possible to the organizations that have the capability and capacity to spend it in such a manner.

So-called “CERP” (Commander’s Emergency Reconstruction Program) funds—funds created by the Coalition Provisional Authority with captured Iraqi money in response to requests from units for funds that could be put to use quickly and with minimal red tape—proved very important in Iraq in the late spring and summer of 2003. These funds en-abled units on the ground to complete thousands of small projects that were, despite their low cost, of enormous importance to local citizens.5 Village schools, for example, could be repaired and refurbished by less than $10,000 at that time, and units like the 101st Airborne Division carried out hundreds of school repairs alone. Other projects funded by CERP in our area included refurbishment of Mosul University, repairs to the Justice Center, numerous road projects, countless water projects, refurbishment of cement and asphalt factories, repair of a massive irrigation system, support for local elections, digging of dozens of wells, repair of police stations, repair of an oil refinery, purchase of uniforms and equipment for Iraqi forces, construction of small Iraqi Army training and operating bases, repairs to parks and swimming pools, support for youth soccer teams, creation of employment programs, refurbishment of medical facilities, creation of a central Iraqi detention facility, establishment of a small business loan program, and countless other small initiatives that made big differences in the lives of the Iraqis we were trying to help.

The success of the CERP concept led Congress to appropriate additional CERP dollars in the fall of 2003, and additional appropriations have continued ever since. Most commanders would agree, in fact, that CERP dollars have been of enormous value to the effort in Iraq (and in Afghanistan, to which the concept migrated in 2003 as well).

Beyond being provided money, those organizations with the capacity and capability to put it to use must also be given reasonable flexibility in how they spend at least a portion of the money, so that it can be used to address emerging needs—which are inevitable. This is particularly important in the case of appropriated funds. The recognition of this need guided our requests for resources for the Iraqi Security Forces “train and equip” mission, and the result was a substantial amount of flexibility in the 2005 supplemental funding measure that has served that mission very well, especially as our new organization achieved the capability and capacity needed to rapidly put to use the resources allocated to it.6

Observation Number 4 reminds us that in-creasing the number of stakeholders is critical to success. This insight emerged several months into our time in Iraq as we began to realize that more important than our winning Iraqi hearts and minds was doing all that we could to ensure that as many Iraqis as possible felt a stake in the success of the new Iraq. Now, I do not want to downplay the importance of winning hearts and minds for the Coalition, as that extends the half-life I described earlier, something that is of obvious desirability. But more important was the idea of Iraqis wanting the new Iraq to succeed. Over time, in fact, we began asking, when considering new initiatives, projects, or programs, whether they would help increase the number of Iraqis who felt they had a stake in the country’s success. This guided us well during the time that the 101st Airborne Division was in northern Iraq and again during a variety of initiatives pursued as part of the effort to help Iraq reestablish its security forces. And it is this concept, of course, that undoubtedly is behind the reported efforts of the U.S. Ambassador in Iraq to encourage Shi’ia and Kurdish political leaders in Iraq to reach out to Sunni Arab leaders and to encourage them to help the new Iraq succeed.

The essence of Observation Number 5—that we should analyze costs and benefits of operations before each operation—is captured in a question we developed over time and used to ask before the conduct of operations: “Will this operation,” we asked, “take more bad guys off the street than it creates by the way it is conducted?” If the answer to that question was, “No,” then we took a very hard look at the operation before proceeding.

In 1986, General John Galvin, then Commander in Chief of the U.S. Southern Command (which was supporting the counterinsurgency effort in El Salvador), described the challenge captured in this observation very effectively: “The . . . burden on the military institution is large. Not only must it subdue an armed adversary while attempting to provide security to the civilian population, it must also avoid furthering the insurgents’ cause. If, for example, the military’s actions in killing 50 guerrillas cause 200 previously uncommitted citizens to join the insurgent cause, the use of force will have been counterproductive.”7

To be sure, there are occasions when one should be willing to take more risk relative to this question. One example was the 101st Airborne Division operation to capture or kill Uday and Qusay. In that case, we ended up firing well over a dozen antitank missiles into the house they were occupying (knowing that all the family members were safely out of it) after Uday and Qusay refused our call to surrender and wounded three of our soldiers during two attempts to capture them.8

In the main, however, we sought to carry out operations in a way that minimized the chances of creating more enemies than we captured or killed. The idea was to try to end each day with fewer enemies than we had when it started. Thus we preferred targeted operations rather than sweeps, and as soon as possible after completion of an operation, we explained to the citizens in the affected areas what we’d done and why we did it.

This should not be taken to indicate that we were the least bit reluctant about going after the Saddamists, terrorists, or insurgents; in fact, the opposite was the case. In one night in Mosul alone, for example, we hit 35 targets simultaneously, getting 23 of those we were after, with only one or two shots fired and most of the operations requiring only a knock on a door, vice blowing it down. Such operations obviously depended on a sophisticated intelligence structure, one largely based on human intelligence sources and very similar to the Joint Interagency Task Forces for Counter-Terrorism that were established in various locations after 9/11.

That, logically, leads to Observation Number 6, which holds that intelligence is the key to success. It is, after all, detailed, actionable intelligence that enables “cordon and knock” operations and precludes large sweeps that often prove counterproductive. Developing such intelligence, however, is not easy. Substantial assets at the local (i.e., division or brigade) level are required to develop human intelligence networks and gather sufficiently precise information to allow targeted operations. For us, precise information generally meant a 10-digit grid for the target’s location, a photo of the entry point, a reasonable description of the target, and directions to the target’s location, as well as other information on the neighborhood, the target site, and the target himself. Gathering this information is hard; considerable intelligence and operational assets are required, all of which must be pulled together to focus (and deconflict) the collection, analytical, and operational efforts. But it is precisely this type of approach that is essential to preventing terrorists and insurgents from putting down roots in an area and starting the process of intimidation and disruption that can result in a catastrophic downward spiral.

Observation Number 7, which springs from the fact that Civil Affairs are not enough when undertaking huge reconstruction and nation-building efforts, is that everyone must do nation-building. This should not be taken to indicate that I have anything but the greatest of respect for our Civil Affairs personnel—because I hold them in very high regard. I have personally watched them work wonders in Central America, Haiti, the Balkans, and, of course, Iraq. Rather, my point is that when undertaking industrial-strength reconstruction on the scale of that in Iraq, Civil Affairs forces alone will not suffice; every unit must be involved.

Reopening the University of Mosul brought this home to those of us in the 101st Airborne Division in the spring of 2003. A symbol of considerable national pride, the University had graduated well over a hundred thousand students since its establishment in 1967. Shortly after the seating of the interim Governor and Province Council in Nineveh Province in early May 2003, the Council’s members established completion of the school year at the University as among their top priorities. We thus took a quick trip through the University to assess the extent of the damage and to discuss reopening with the Chancellor. We then huddled with our Civil Affairs Battalion Commander to chart a way ahead, but we quickly found that, although the talent inherent in the Battalion’s education team was impressive, its members were relatively junior in rank and its size (numbering less than an infantry squad) was simply not enough to help the Iraqis repair and reopen a heavily-looted institution of over 75 buildings, some 4,500 staff and faculty, and approximately 30-35,000 students. The mission, and the education team, therefore, went to one of the two aviation brigades of the 101st Airborne Division, a brigade that clearly did not have “Rebuild Foreign Academic Institutions” in its mission essential task list. What the brigade did have, however, was a senior commander and staff, as well as numerous subordinate units with commanders and staffs, who collectively added up to considerable organizational capacity and capability.

Seeing this approach work with Mosul University, we quickly adopted the same approach in virtually every area—assigning a unit or element the responsibility for assisting each of the Iraqi Ministries’ activities in northern Iraq and also for linking with key Iraqi leaders. For example, our Signal Battalion incorporated the Civil Affairs Battalion’s communications team and worked with the Ministry of Telecommunications element in northern Iraq, helping reestablish the local telecommunications structure, including assisting with a deal that brought a satellite downlink to the central switch and linked Mosul with the international phone system, producing a profit for the province (subscribers bore all the costs). Our Chaplain and his team linked with the Ministry of Religious Affairs, the Engineer Battalion with the Ministry of Public Works, the Division Support Command with the Ministry of Youth and Sports, the Corps Support Group with the Ministry of Education, the Military Police Battalion with the Ministry of Interior (Police), our Surgeon and his team with the Ministry of Health, our Staff Judge Advocate with Ministry of Justice officials, our Fire Support Element with the Ministry of Oil, and so on. In fact, we lined up a unit or staff section with every ministry element and with all the key leaders and officials in our AOR, and our subordinate units did the same in their areas of responsibility. By the time we were done, everyone and every element, not just Civil Affairs units, was engaged in nation-building.

Observation Number 8, recognition of the need to help build institutions, not just units, came from the Coalition mission of helping Iraq reestablish its security forces. We initially focused primarily on developing combat units—Army and Police battalions and brigade headquarters—as well as individual police. While those are what Iraq desperately needed to help in the achievement of security, for the long term there was also a critical need to help rebuild the institutions that support the units and police in the field—the ministries, the admin and logistical support units, the professional military education systems, admin policies and procedures, and the training organizations. In fact, lack of ministry capability and capacity can undermine the development of the battalions, brigades, and divisions, if the ministries, for example, don’t pay the soldiers or police on time, use political rather than professional criteria in picking leaders, or fail to pay contractors as required for services provided. This lesson underscored for us the importance of providing sufficient advisors and mentors to assist with the development of the security ministries and their elements, just as we provided advisor teams with each battalion and each brigade and division headquarters.9

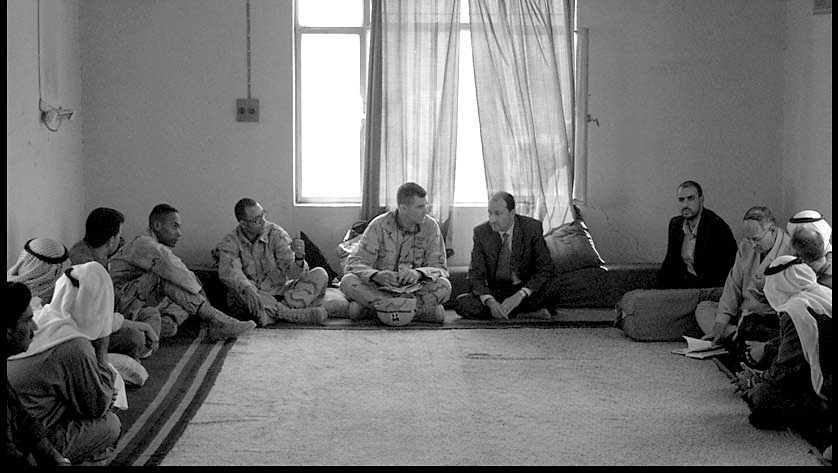

Observation Number 9, cultural awareness is a force multiplier, reflects our recognition that knowledge of the cultural “terrain” can be as important as, and sometimes even more important than, knowledge of the geographic terrain. This observation acknowledges that the people are, in many respects, the decisive terrain, and that we must study that terrain in the same way that we have always studied the geographic terrain.

Working in another culture is enormously difficult if one doesn’t understand the ethnic groups, tribes, religious elements, political parties, and other social groupings—and their respective viewpoints; the relationships among the various groups; governmental structures and processes; local and regional history; and, of course, local and national leaders. Understanding of such cultural aspects is essential if one is to help the people build stable political, social, and economic institutions. Indeed, this is as much a matter of common sense as operational necessity. Beyond the intellectual need for the specific knowledge about the environment in which one is working, it is also clear that people, in general, are more likely to cooperate if those who have power over them respect the culture that gives them a sense of identity and self-worth.

In truth, many of us did a lot of “discovery learning” about such features of Iraq in the early months of our time there. And those who learned the quickest—and who also mastered some “survival Arabic”—were, not surprisingly, the most effective in developing productive relationships with local leaders and citizens and achieved the most progress in helping establish security, local governance, economic activity, and basic services. The importance of cultural awareness has, in fact, been widely recognized in the U.S. Army and the other services, and it is critical that we continue the progress that has been made in this area in our exercises, military schools, doctrine, and so on.10

Observation Number 10 is a statement of the obvious, fully recognized by those operating in Iraq, but it is one worth recalling nonetheless. It is that success in a counterinsurgency requires more than just military operations. Counterinsurgency strategies must also in-clude, above all, efforts to establish a political environment that helps reduce support for the insurgents and undermines the attraction of whatever ideology they may espouse.11 In certain Sunni Arab regions of Iraq, establishing such a political environment is likely of greater importance than military operations, since the right political initiatives might undermine the sanctuary and assistance provided to the insurgents. Beyond the political arena, other important factors are economic recovery (which reduces unemployment, a serious challenge in Iraq that leads some out-of-work Iraqis to be guns for hire), education (which opens up employment possibilities and access to information from outside one’s normal circles), diplomatic initiatives (in particular, working with neighboring states through which foreign fighters transit), improvement in the provision of basic services, and so on. In fact, the campaign plan developed in 2005 by the Multinational Force-Iraq and the U.S. Embassy with Iraqi and Coalition leaders addresses each of these issues.

Observation Number 11—ultimate success depends on local leaders—is a natural reflection of Iraqi sovereignty and acknowledges that success in Iraq is, as time passes, increasingly dependent on Iraqi leaders—at four levels:

- Leaders at the national level working together, reaching across party and sectarian lines to keep the country unified, rejecting short-term expedient solutions such as the use of militias, and pursuing initiatives to give more of a stake in the success of the new Iraq to those who feel left out;

- Leaders in the ministries building the capability and capacity necessary to use the tremendous resources Iraq has efficiently, transparently, honestly, and effectively;

- Leaders at the province level resisting temptations to pursue winner-take-all politics and resisting the urge to politicize the local police and other security forces, and;

- Leaders in the Security Forces staying out ofpolitics, providing courageous, competent leadership to their units, implementing policies that are fair to all members of their forces, and fostering loyalty to their Army or Police band of brothers rather than to specific tribes, ethnic groups, political parties, or local militias.

Iraqi leaders are, in short, the real key to the new Iraq, and we thus need to continue to do all that we can to enable them.

Observation Number 12 is the admonition to remember the strategic corporals and strategic lieutenants, the relatively junior commissioned or noncommissioned officers who often have to make huge decisions, sometimes with life-or-death as well as strategic consequences, in the blink of an eye.

Commanders have two major obligations to these junior leaders: first, to do everything possible to train them before deployment for the various situations they will face, particularly for the most challenging and ambiguous ones; and, second, once deployed, to try to shape situations to minimize the cases in which they have to make those hugely important decisions extremely quickly.

The best example of the latter is what we do to help ensure that, when establishing hasty checkpoints, our strategic corporals are provided sufficient training and adequate means to stop a vehicle speeding toward them without having to put a bullet through the windshield. This is, in truth, easier said than it is done in the often chaotic situations that arise during a fast-moving operation in such a challenging security environment. But there are some actions we can take to try to ensure that our young leaders have adequate time to make the toughest of calls—decisions that, if not right, again, can have strategic consequences.

My next-to-last observation, Number 13, is that there is no substitute for flexible, adaptable leaders. The key to many of our successes in Iraq, in fact, has been leaders—especially young leaders—who have risen to the occasion and taken on tasks for which they’d had little or no training,12 and who have demonstrated enormous initiative, innovativeness, determination, and courage.13 Such leaders have repeatedly been the essential ingredient in many of the achievements in Iraq. And fostering the development of others like them clearly is critical to the further development of our Army and our military.14

My final observation, Number 14, underscores that, especially in counterinsurgency operations, a leader’s most important task is to set the right tone. This is, admittedly, another statement of the obvious, but one that nonetheless needs to be highlighted given its tremendous importance. Setting the right tone and communicating that tone to his subordinate leaders and troopers are absolutely critical for every leader at every level, especially in an endeavor like that in Iraq.

If, for example, a commander clearly emphasizes so-called kinetic operations over non-kinetic operations, his subordinates will do likewise. As a result, they may thus be less inclined to seize opportunities for the nation-building aspects of the campaign. In fact, even in the 101st Airborne Division, which prided itself on its attention to nation-building, there were a few mid-level commanders early on whose hearts really weren’t into performing civil affairs tasks, assisting with reconstruction, developing relationships with local citizens, or helping establish local governance. To use the jargon of Iraq at that time, they didn’t “get it.” In such cases, the commanders above them quickly established that nation-building activities were not optional and would be pursued with equal enthusiasm to raids and other offensive operations.

Setting the right tone ethically is another hugely important task. If leaders fail to get this right, winking at the mistreatment of detainees or at manhandling of citizens, for example, the result can be a sense in the unit that “anything goes.” Nothing can be more destructive in an element than such a sense.

In truth, regardless of the leader’s tone, most units in Iraq have had to deal with cases in which mistakes have been made in these areas, where young leaders in very frustrating situations, often after having suffered very tough casualties, took missteps. The key in these situations is for leaders to ensure that appropriate action is taken in the wake of such incidents, that standards are clearly articulated and reinforced, that remedial training is conducted, and that supervision is exercised to try to preclude recurrences.

It is hard to imagine a tougher environment than that in some of the areas in Iraq. Frustrations, anger, and resentment can run high in such situations. That recognition underscores, again, the importance of commanders at every level working hard to get the tone right and to communicate it throughout their units.

Implications

These are, again, 14 observations from soldiering in Iraq for most of the first 2-1/2 years of our involvement there. Although I presented them as discrete lessons, many are inextricably related. These observations carry with them a number of implications for our effort in Iraq (and for our Army as well, as I have noted in some of the footnotes).15

It goes without saying that success in Iraq—which clearly is important not just for Iraq, but for the entire Middle East region and for our own country—will require continued military operations and support for the ongoing development of Iraqi Security Forces.

Success will also require continued assistance and resources for the development of the emerging political, economic, and social institutions in Iraq—efforts in which Ambassador Zalmay Khalilzad and General George Casey and their teams have been engaged with their Iraqi counterparts and have been working very hard.

Lastly, success will require time, determination, and resilience, keeping in mind that following the elections held in mid-December 2005, several months will likely be required for the new government—the fourth in an 18-month period—to be established and functional. The insurgents and extremists did all that they could to derail the preparations for the constitutional referendum in mid-October and the elections in mid-December. Although they were ineffective in each case, they undoubtedly will try to disrupt the establishment of the new government—and the upcoming provincial elections—as well. As Generals John Abizaid and George Casey made clear in their testimony on Capitol Hill in September 2005, however, there is a strategy—developed in close coordination with those in the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad and with our inter-agency, Coalition, and Iraqi partners—that addresses the insurgency, Iraqi Security Forces, and the other relevant areas. And there has been substantial progress in a number of areas. Nonetheless, nothing is ever easy in Iraq and a great deal of hard work and many challenges clearly lie ahead.16

The first 6 months of 2006 thus will be of enormous importance, with the efforts of Iraqi leaders being especially significant during this period as a new government is seated and the new constitution enters into force. It will be essential that we do all that we can to support Iraq’s leaders as they endeavor to make the most of the opportunity our Soldiers have given them.

Conclusion

In a 1986 article titled “Uncomfortable Wars: Toward a New Paradigm,” General John R. Galvin observed that “[a]n officer’s effectiveness and chance for success, now and in the future, depend not only on his character, knowledge, and skills, but also, and more than ever before, on his ability to understand the changing environment of conflict.17 General Galvin’s words were relevant then, but they are even more applicable today. Conducting counterinsurgency operations in a vastly different culture is exceedingly complex.

Later, in the same article, noting that we in the military typically have our noses to the grindstone and that we often live a somewhat cloistered existence, General Galvin counseled: “Let us get our young leaders away from the grindstone now and then, and encourage them to reflect on developments outside the fortress-cloister. Only then will they develop into leaders capable of adapting to the changed environment of warfare and able to fashion a new paradigm that addresses all the dimensions of the conflicts that may lie ahead.”18

Given the current situation, General Galvin’s advice again appears very wise indeed. And it is my hope that, as we all take time to lift our noses from the grindstone and look beyond the confines of our current assignments, the observations provided here will help foster useful discussion on our ongoing endeavors and on how we should approach similar conflicts in the future—conflicts that are likely to be the norm, rather than the exception, in the 21st century.

Notes

- The Center for Army Lessons Learned website can be found at <http://call.Army.mil/>.

- T.E. Lawrence, “Twenty-Seven Articles,” Arab Bulletin (20 August 1917). Known popularly as “Lawrence of Arabia,” T.E. Lawrence developed an incomparable degree of what we now call “cultural awareness” during his time working with Arab tribes and armies, and many of his 27 articles ring as true today as they did in his day. A website with the articles can be found at https://www.pbs.org/lawrenceofarabia/revolt/warfare4.html. A good overview of Lawrence’s thinking, including his six fundamental principles of insurgency, can be found in “T.E. Lawrence and the Mind of an Insurgent,” Army (July 2005): 31-37.

- I should note that this has been much less the case in Afghanistan where, because the expectations of the people were so low and the abhorrence of the Taliban and further civil war was so great, the Afghan people remain grateful to Coalition forces and other organizations for all that is done for them. Needless to say, the relative permissiveness of the security situation in Afghanistan has also helped a great deal and made it possible for nongovernmental organizations to operate on a much wider and freer basis than is possible in Iraq. In short, the different context in Afghanistan has meant that the half-life of the Army of liberation there has been considerably longer than that in Iraq.

- In fact, we often contended with what came to be known as the “Man on the Moon Challenge”—i.e., the expectation of ordinary Iraqis that soldiers from a country that could put a man on the moon and overthrow Saddam in a matter of weeks should also be able, with considerable ease, to provide each Iraqi a job, 24-hour electrical service, and so on.

- The military units on the ground in Iraq have generally had considerable capability to carry out reconstruction and nation-building tasks. During its time in northern Iraq, for example, the 101st Airborne Division had 4 engineer battalions (including, for a period, even a well-drilling detachment), an engineer group headquarters (which is designed to carry out assessment, design, contracting, and quality assurance tasks), 2 civil affairs battalions, 9 infantry battalions, 4 artillery battalions (most of which were “out of battery” and performed reconstruction tasks), a sizable logistical support command (generally about 6 battalions, including transportation, fuel storage, supply, maintenance, food service, movement control, warehousing, and even water purification units), a military police battalion (with attached police and corrections training detachments), a signal battalion, an air defense battalion (which helped train Iraqi forces), a field hospital, a number of contracting officers and officers authorized to carry large sums of money, an air traffic control element, some 9 aviation battalions (with approximately 250 helicopters), a number of chaplain teams, and more than 25 military lawyers (who can be of enormous assistance in resolving a host of problems when conducting nation-building). Except in the area of aviation assets, the 4th Infantry Division and the 1st Armored Division, the two other major Army units in Iraq in the summer of 2003, had even more assets than the 101st.

- The FY 2005 Defense Budget and Supplemental Funding Measures approved by Congress provided some $5.2 billion for the Iraqi Security Force’s train, equip, advise, and rebuild effort. Just as significant, it was appropriated in just three categories—Ministry of Defense, Ministry of Interior, and Quick Reaction Funds—thereby minimizing substantially the need for reprogramming actions.

- General John R. Galvin, “Uncomfortable Wars: Toward a New Paradigm,” Parameters, 16, no. 4 (Winter 1986): 6.

- As soon as the “kinetic” part of that operation was complete, we moved into the neighborhood with engineers, civil affairs teams, lawyers, officers with money, and security elements. We subsequently repaired any damage that might conceivably have been caused by the operation, and completely removed all traces of the house in which Uday and Qusay were located, as the missiles had rendered it structurally unsound and we didn’t want any reminders left of the two brothers.

- Over time, and as the effort to train and equip Iraqi combat units gathered momentum, the Multinational Security Transition Command–Iraq placed greater and greater emphasis on helping with the development of the Ministries of Defense and Interior, especially after the mission to advise the Ministries’ leaders was shifted to the Command from the Embassy’s Iraq Reconstruction Management Office in the Fall of 2005. It is now one of the Command’s top priorities.

- The Army, for example, has incorporated scenarios that place a premium on cultural awareness into its major exercises at the National Training Center and Joint Readiness Training Center. It has stressed the importance of cultural awareness throughout the process of preparing units for deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan and in a comprehensive approach adopted by the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command. As part of this effort, language tools have been developed; e.g., the Rosetta Stone program available through Army Knowledge Online, and language training will be required; e.g., of Command and General Staff College students during their 2d and 3d semesters. Doctrinal manuals are being modified to recognize the importance of cultural awareness, and instruction in various commissioned and noncommissioned officer courses has been added as well. The Center for Army Lessons Learned has published a number of documents to assist as well. The U.S. Marine Corps has pursued similar initiatives and is, in fact, partnering with the Army in the development of a new Counterinsurgency Field Manual.

- David Galula’s classic work, Counterinsurgency Warfare: Theory and Practice (St. Petersburg, FL: Hailer Publishing, 2005) is particularly instructive on this point. See, for example, his discussion on pages 88-89.

- As I noted in a previous footnote, preparation of leaders and units for deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan now typically includes extensive preparation for the kind of “non-kinetic” operations our leaders are called on to perform, with the preparation period culminating in a brigade combat team mission rehearsal exercise at either the National Training Center or the Joint Readiness Training Center. At each Center, units conduct missions similar to those they’ll perform when deployed and do so in an environment that includes villages, Iraqi-American role players, “suicide bombers,” “insurgents,” the need to work with local leaders and local security forces, etc. At the next higher level, the preparation of division and corps headquarters culminates in the conduct of a mission rehearsal exercise conducted jointly by the Battle Command Training Program and Joint Warfighting Center. This exercise also strives to replicate—in a command post exercise format driven by a computer simulation—the missions, challenges, and context the unit will find once deployed.

- A great piece that highlights the work being done by young leaders in Iraq is Robert Kaplan’s “The Future of America—in Iraq,” latimes.com, 24 December 2005. Another is the video presentation used by Army Chief of Staff General Peter J. Schoomaker, “Pentathlete Leader: 1LT Ted Wiley,” which recounts Lieutenant Wiley’s fascinating experiences in the first Stryker unit to operate in Iraq as they fought and conducted nation-building operations throughout much of the country, often transitioning from one to the other very rapidly, changing missions and reorganizing while on the move, and covering considerable distances in short periods of time.

- In fact, the U.S. Army is currently in the final stages of an important study of the education and training of leaders, one objective of which is to identify additional programs and initiatives that can help produce the kind of flexible, adaptable leaders who have done well in Iraq and Afghanistan. Among the issues being examined is how to provide experiences for our leaders that take them out of their “comfort zone.” For many of us, attending a civilian graduate school provided such an experience, and the Army’s recent decision to expand graduate school opportunities for officers is thus a great initiative. For a provocative assessment of the challenges the U.S. Army faces, see the article by U.K. Brigadier Nigel Aylwin-Foster, “Changing the Army for Counterinsurgency Operations,” Military Review (November-December 2005): 2-15.

- The Department of Defense (DOD) formally recognized the implications of current operations as well, issuing DOD Directive 3000.05 on 28 November 2005, “Military Support for Stability, Security, Transition, and Reconstruction Operations,” which establishes DOD policy and assigns responsibilities within DOD for planning, training, and preparing to conduct and support stability operations. This is a significant action that is already spurring action in a host of different areas. A copy can be found at www.dtic.mil/whs/directives/corres/html/300005.htm

- A brief assessment of the current situation and the strategy for the way ahead is in Ambassador Zalmay Khalilzad’s “The Challenge Before Us,” Wall Street Journal, 9 January 2006, 12.

- 17. Galvin, 7. One of the Army’s true soldier-statesman-scholars, General Galvin was serving as the Commander in Chief of U.S. Southern Command at the time he wrote this article. In that position, he oversaw the conduct of a number of operations in El Salvador and elsewhere in Central and South America, and it was in that context that he wrote this enduring piece. He subsequently served as the Supreme Allied Commander, Europe, and following retirement, was the Dean of the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University, Medford, Massachuesetts.

- Ibid.

Lieutenant General David H. Petraeus, U.S. Army, took command of the Combined Arms Center and Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, in October 2005. He also serves as the Commandant of the Command and General Staff College and as Deputy Commander for Combined Arms of the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command. LTG Petraeus commanded the 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) in Iraq during the first year of Operation Iraqi Freedom, returning to the United States with the Division in mid-February 2004. He returned to Iraq for several weeks in April and May 2004 to assess the Iraqi Security Forces, and he subsequently returned in early June 2004 to serve as the first commander of the Multi-National Security Transition Command-Iraq, the position he held until September 2005. In late 2004, he also became the first commander of the NATO Training Mission-Iraq. Prior to his tour with the 101st, he served for a year as the Assistant Chief of Staff for Operations of the NATO Stabilization Force in Bosnia. A graduate of the U.S. Military Academy, LTG Petraeus earned M.P.A. and Ph.D. degrees from Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs.

Back to Top